An Indy News Analysis. PAYING FOR BIG CAPITAL PROJECTS: LESSONS FROM A SPREADSHEET

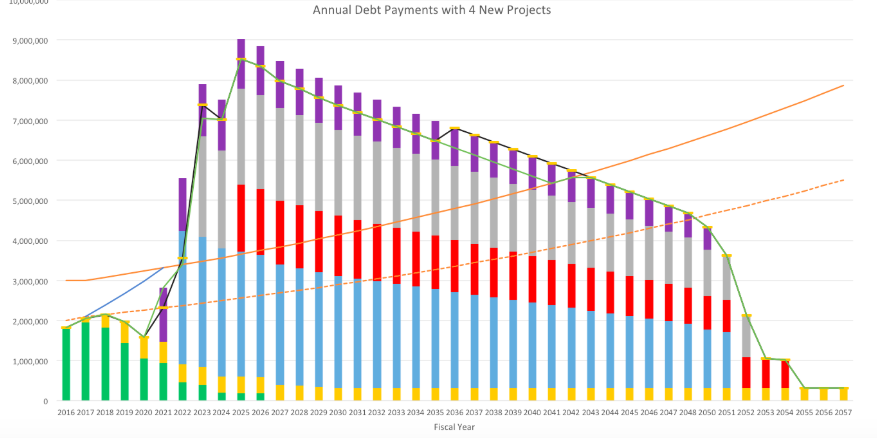

Bar graph derived from the original Pooler budget tool projecting annual debt payments on four major capital projects. See Figure 1 in article for key. Photo: Stephen Braun.

In 2015, the town’s finance director, Sandy Pooler, created an interactive Excel spreadsheet to allow Finance Committee members to experiment with different scenarios for funding the “big four” capital projects that will be the topic of upcoming “listening sessions” held by the Town Council. The spreadsheet allows users to manipulate a set of variables relevant to the construction of a new school, fire station, and DPW facility, as well as to the proposed reconstruction/renovation of the Jones Library. Those variables include total cost, percentage of reimbursement from state agencies (if available), bond lengths and timings, and whether a project is funded via the annual capital budget or a debt exclusion override. (More about overrides below).

The Pooler spreadsheet was never made public because it was relatively complex to use and interpret. An updated and more streamlined version of the spreadsheet tool was created by outgoing School Finance Director Sean Mangano this year. Mangano demonstrated one version of the tool to the Council at its February 25, 2019 meeting.

According to those familiar with the tool’s development, a final version is not yet complete and a decision about whether to make it available to the public has not yet been made. The tool is still relatively complex and many key variables (not least, total project costs) remain uncertain. Some town leaders feel it would be counterproductive to post the tool on the town’s website without better instructions about its use an interpretation.

The original Pooler spreadsheet and its updated incarnation can help guide decisions about how to pay for the capital projects, although actual decisions about those projects will be driven by factors beyond those captured in a spreadsheet. For example, the Massachusetts Board of Library Commissioners has told the Jones Library trustees that in July 2020 it will award Amherst a grant to help fund the proposed rebuild/renovation project. (The library may have an option to delay a decision for six months.) Meanwhile, the Massachusetts School Building Authority will not have made any final decisions about a grant for an elementary school, because even if Amherst gets a green light next week on its Statement of Interest, it will probably take at least a year before a final plan for a building and an educational plan could be developed, submitted, and approved. This may force a decision about whether, and how, to pay for the library project. That decision, in turn, will affect how much money the town has to pay for the other projects.

As a former Finance Committee member, I have a copy of Pooler’s spreadsheet. For a variety of reasons, including that much of the data “under the hood” of the spreadsheet is out of date and the fact that some of Pooler’s basic assumptions are unclear, this spreadsheet would not be very helpful as a publicly-available tool. Nonetheless, it can be used to generate some images that, I hope, will help interested citizens think more clearly about town options before the upcoming listening sessions.

A Quick Tutorial

The Pooler spreadsheet generates a bar chart showing how much the town would have to pay every year to service the debt incurred from borrowing money (in the form of bonds) for various capital projects (Figure 1). It displays these bars against two gently-sloping lines curving up to the right. The solid orange line is the one to look at—it represents Pooler’s estimate of how much money the town will actually have for debt payments given an assumption that the total capital budget is at 10% of the town’s total tax levy and that roughly half of each year’s capital budget is devoted to debt repayment. Note that the chart does NOT show the portion of each year’s capital budget that is spent directly (i.e., without borrowing) on needed items such as new vehicles, equipment, computers, lawnmowers and all the other tangible things the town needs each year. (And if these last couple of sentences make your eyes cross, hang in there…more explanation will follow.)

Figure 1 illustrates the central conundrum facing the town as it considers the Big Four capital projects. The solid orange line is, again, how much the town can afford under the assumption that we spend 10% of our total property tax receipts in a given year on our capital budget. Currently, the town uses 9.5% of the levy on capital, and the Town Manager has recommended that we spend 10% in the next fiscal year. Reaching the 10% mark is an impressive achievement for the town—we have been very slowly re-building our annual capital budgets in the past decade or so when we were spending as little as 7% of the levy on capital needs.

Each of the bars on the graph shows the debt service on the bonds for various projects. The green bars represent existing debt—money we owe for things we’ve already borrowed for (for example, a new roof on the high school). These green bars show that our outstanding debt is rapidly dwindling to near zero, which frees up money that we can use to repay new debts.

The yellow bars are a “fudge factor” that Pooler included to allow for spending on smaller things we might need to borrow money for—a new firetruck, for example. His assumption was that we’d need to borrow about $500,000 every 5 years for such things, which is a low estimate, based on my experience as a former member of the Joint Capital Planning Committee.

The purple bars represent the debt for the library project, the grey bars represent the DPW project, the red bars are for the fire station, and the blue bars are for the school(s) project. Figure 1 uses the following (still very uncertain) costs of each project, taken from this year’s Joint Capital Planning Committee report: $16 million for library (the town’s share—the total cost will be more because of state grant); $30 million for DPW; $20 million for Fire station; and $40 million for the school(s) (again, this is the town’s share—the total cost of the project currently under consideration will be about double that, but the state will pay roughly half). The bars are based on an assumption of 30-year bonds with a roughly 4.5% interest rate, with the following sequence of construction: library in 2021, elementary school in 2022, DPW in 2023, and fire station in 2025. DPW comes before the fire station because several studies have suggested that the optimal spot for a new fire station is on the South Pleasant St. property the town now uses for the main DPW facility. The idea, therefore, is to build the new DPW facility on another parcel, then tear down the old facility and build a new fire station.

Even allowing for the considerable uncertainty in the actual costs of the four projects, the problem is obvious: the town cannot afford all of the Big Four projects even if they are staggered between 2021 and 2025. (It’s also true that there is at least one other “big project” that the town will need to pay for: road and sidewalk repairs. This is actually an important issue that shouldn’t get lost in the discussions about the four projects that are the focus of the current “listening sessions” but, for this analysis, I will stick to the projects in Pooler’s original spreadsheet.)

If we can’t afford to pay for the “Big Four” from our existing capital budget, how can we make progress? Several options exist.

Option 1: Reduce Construction Costs

Even though the cost estimates by JCPC are preliminary, they are not completely arbitrary and it is simply not possible to reduce the costs of a school, DPW facility, or fire station significantly from the current estimates. If anything, the estimates may be low. The only project for which the overall construction cost could conceivably be significantly lower is the library. If the current is not accepted and a much more modest set of upgrades and repairs (for example for the roof, HVAC system, and elevator) were approved, the cost to the town could be much lower, although a much-reduced scope of work would mean the town would have to forgo state aid, so the actual cost savings would be less than one might expect.

Option 2: Spread Out Construction Over Time

The DPW and fire station projects have already been delayed for several decades and their respective buildings are woefully inadequate in a myriad of ways, so delaying these projects by many more years, or decades, is not tenable. The school project construction date will be driven by the MSBA. A decision on the town’s Statement of Interest is due within a week, but, as noted earlier, the town then must form a building committee, hire a consultant, review building and education plans, approve a final plan, and submit it to MSBA for approval. If the project is approved, the town must then begin work immediately. It cannot just take the state money and delay construction for several years. But, for the sake of argument, let’s say we did space out the projects significantly. Here’s what the graph looks like with the following construction dates: library in 2021, elementary school in 2025, DPW in 2030, and fire station in 2035:

You can see that even with this unrealistic extension, the total debt payments exceed the town’s capacity starting in 2025 and continuing for 20 years.

Option 3: Devote More Money to the Capital Budget/Debt Repayment

If the town decided to devote, say, 20% of the tax levy to the capital budget, then it’s conceivable that we could pay for the debt service on all four projects. But that money would have to come from the town’s operating budget, the bulk of which pays for the salaries of teachers, fire fighters, police officers, town and school administrators, and all of the services the town currently enjoys. Making the operating budget cuts required to shift money to debt repayment would mean laying off many dozens of staff. (How many exactly? To my knowledge nobody has done that exercise because the impacts would be so drastic.) A related option would be to devote the entire capital budget to debt repayment. In fiscal year 2020 the town will spend about $2 million of the roughly $5 million available from the levy on debt payment, or about 40%. We could increase that percentage—and may have to, at least slightly, but that means less money for all of the equipment, vehicles, maintenance, building repairs, and other year-to-year (i.e., not borrowed) capital needs of the town. Doing so would not only impair the ability of the town to support desired services, it would plausibly increase long-term costs by deferring work on problems that will only get worse with time.

Option 4: Use The Town’s Stabilization Fund to Pay for Debt Service

The stabilization fund is one part of the town’s reserve funds and is designed to help the town weather unexpected financial difficulties, such as reductions in state aid due to an economic downturn, or unexpected expenses due to natural disasters or other serious challenges. The stabilization fund currently has about $10 million in it, which is about what the Finance Committee recommends as prudent for a town the size of Amherst. It would be possible to use some of this fund to help pay the debt on a capital project, but this, of course, would reduce the town’s “cushion” for dealing with future financial needs. Using a part of the stabilization fund may be part of the larger scheme to help fund the capital projects, for example by paying for a few years in which the total debt exceeds the town’s capacity by some relatively small amount (for example, $500,000). But the stabilization fund is simply not large enough to prudently draw upon in any significant way over the life of a 20- or 30-year bond.

Option 5: Encourage More Economic Development

In FY 2020 new economic development in town added about $800,000 to the town’s coffers. The money allowed for some very modest increases in the operating budgets for the town, schools, and library. If the town made it easier for developers to build more, or larger, housing or commercial developments, that could, over time, generate more tax revenue that could be devoted to debt service. The problem with this option is that a) many people are opposed to more/bigger developments, particularly downtown, b) it’s not clear there are actually that many places in town appropriate for big new developments, and c) revenue from new development is both unpredictable and prone to yearly fluctuations, both of which are untenable when the town faces fixed bond repayment schedules.

Option 6: Pay for One or Two Projects with a Debt-Exclusion Override

First, some background. What is a debt-exclusion override?

Massachusetts towns can only raise town property tax rates by 2.5% each year under state law. But an exception exists because the state recognizes that sometimes towns need to pay for big-ticket items such as new schools, fire stations, or libraries. The exception is a debt-exclusion override. This allows the town to increase taxes beyond the 2.5% limit in order to repay the loans (typically bonds) used for big projects by “excluding” those payments from the 2.5% limit. When the loans for a project are paid off (which could take as long as 30 years), the override disappears and the town reverts to the 2.5% taxing limit. Overrides are project-specific and must be put to the voters for approval by a simple majority. Although the law is not entirely clear on this point, I believe that towns cannot lump several projects together and ask voters to pay for them via a single override, although a single ballot could contain questions about multiple overrides.

The effect of an override on taxpayers depends on the amount of money borrowed and the value of the taxpayer’s property. The Pooler spreadsheet calculates the impact of an override on a taxpayer with an “average” residential property value of roughly $320,000, which is now slightly out of date, but still provides a helpful approximation. For example, an override for a $40 million project would increase the average property owner’s taxes about $360 averaged over the life of the loan. Whether the actual yearly override-associated tax increase would remain fixed from year to year or decrease over time depends on how the debt is structured, which is a decision that will be made by the town’s financial experts based on all sorts of variables beyond the scope of this article.

Since the elementary school project is the most expensive of the four and, plausibly, could garner the most support from the voters, it makes sense to look at what would happen to our spreadsheet graph if we remove the school project (because it’ll be funded by the override).

You can see that there’s a big improvement from the state of affairs modeled in Figure 1. We still exceed the town’s repayment capacity for about a decade, but there are really significant overages in only about five of the years, which could plausibly be covered by extra money from the stabilization fund, new development revenue, new revenue from cannabis taxes, or some adjustments to the operating budget. If the DPW and fire station construction dates were extended a bit, things improve even more, as shown in Figure 4.

We could reach a similarly feasible scenario if we kept the original construction dates for DPW and fire (i.e., 2023 and 2025) but cut the library project from $16 million to, say, $5 million, as Figure 5 shows.

Another option that is at least theoretically possible would be to pay for two projects with separate overrides. For example, the town’s share of the library project could be paid for with an override, and then, a couple of years later, an override could be put on the ballot for the school project. This would certainly free up resources and make everything more doable from a town borrowing and financial standpoint, but it would make the annual additional tax more burdensome—from and average of $360 each year to $506 each year. Whether voters would approve two separate overrides is an open question, of course…and whether voters would be more likely to approve an override for, say, a fire station than a library expansion is also unpredictable.

Final thoughts

In my view, these are the lessons from experimenting with the Pooler spreadsheet:

- We cannot afford all four projects (or even 3 with a much-reduced library project) without an override.

- If we need an override, it makes sense to use it for the school project.

- We cannot afford the projects if construction costs are much higher than the estimates used in the models above. This suggests that the town approach consultants who develop schematics and building plans with clear, firm up-front guidelines about what the town can, and cannot, afford.

It bears repeating that the scenarios outlined above, including the estimated override-associated tax increases, are just that…scenarios. The further out one looks in time, the less reliable are predictions for things like construction costs, interest rates, and town revenue available for capital. Even with these caveats, this kind of analysis can help clarify thinking, both for town decision-makers and the citizens who will foot the bill for those decisions.

Stephen Braun served on the Finance Committee from 2014 through 2017, and is a member of the Indy’s Editorial Board.

If the expected lifetimes of these assets exceeds half a century, would another potential cost-saving option be to float bonds of comparable duration (50 years, say)?

Rob Kusner