OPINION: WHAT DOES A POST-PANDEMIC LIBRARY LOOK LIKE?

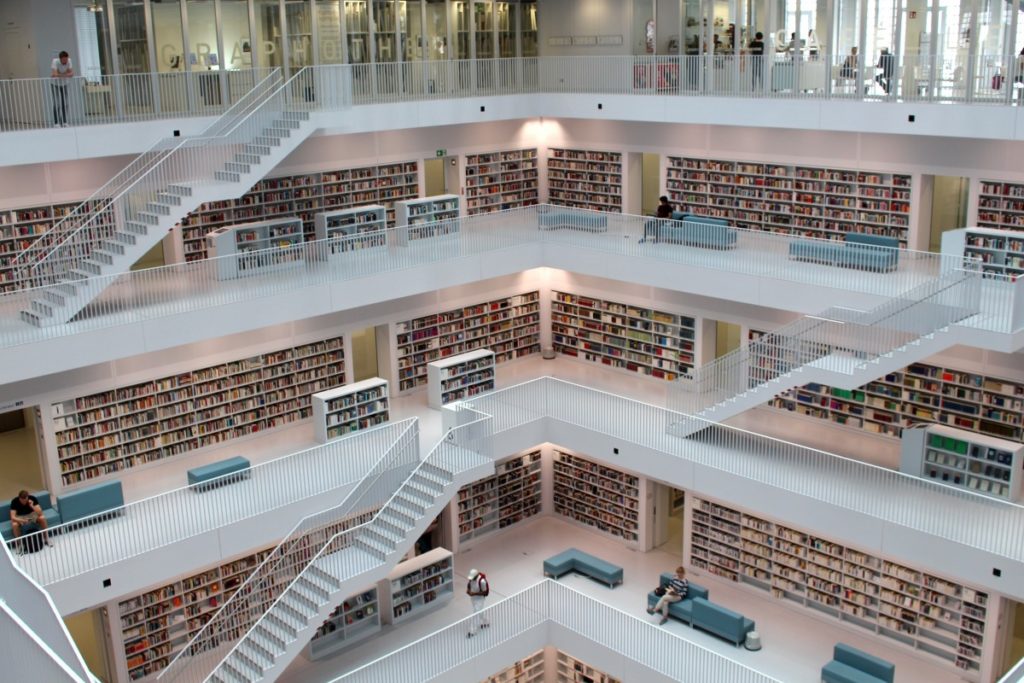

City Library, Stuttgart, Germany. Photo: pixhere.com

Elsewhere in this issue I wrote about the urgent need for us to have community conversations about imagining a post-pandemic world; conversations that consider not just recovery from the pandemic but also how we think the world ought to be. I noted that we need to raise questions on multiple scales from the grand (e.g. in what ways should we be responsible to each other), to the granular (e.g. how do we feed the hungry in our midst). This column is a brief excursion into the latter end of that spectrum.

The Town will soon have to decide whether to move forward with a proposed demolition and expansion project for the Jones Library and must do so in the midst of a challenging budget crisis resulting from the pandemic. Here I will not consider the pros and cons of the project that have been explored in previous articles in the Indy (see here, here and here). Instead, independent of the merits of that project, I would like us to imagine what a post-pandemic library might/should look like and how might we optimally design our library or any library, to better serve us during placid times as well as during an emergency like the one that currently envelopes our lives?

These questions were explored in two recent articles in The Atlantic by Deborah and James Fallows (see here and here). The authors document an impressive array of adaptations and innovations amongst American libraries that have enabled them, while operating under closure orders, to continue to deliver services and indeed to expand services, in order to meet growing needs of patrons contending with an array of new challenges posed by the pandemic, (see also the webinar, Public Libraries Respond To COVID-19).

They note that even before librarians closed their doors against the pandemic, “…they started moving fast to keep their work going. They began shifting regular programming online; distributing stockpiles of mobile technology to the digitally needy; strengthening partnerships with schools and food donation sites; activating their maker-technology to produce PPE; helping prepare the homeless population with alternatives for shelter; and more.”

Our own Jones Library offers an impressive array of online services and programs during the pandemic.

So how has the pandemic shaped our imagination for what a community library should be? Our challenge is to consider how a library (or library system) can optimize the services that it provides in its physical structure, while at the same time providing for continuity of services should the building be forced to close. What essential services can/should the library provide for the community? And how can the delivery of such services be ensured under emergency conditions? And how would a library prioritize the needs it proposes to meet, in/for the community, so that its response to an emergency is planned for and those relying on library services are not abandoned?

Some Ideas

Expanding Virtual Services: Many libraries are now expanding their virtual services in response to the pandemic and indeed, are prioritizing the expansion. Many were unable to meet the unanticipated demand that occurred when libraries were physically closed and consequently are planning to aggressively expand virtual programming, access to ebooks and streaming services, as well as the maintenance of social media platforms. Virtual programming, however, does not come cheap, and requires specialized staffing and expanded server capacity. But an expanded virtual presence enables a library to continue to serve patrons who have internet access, under the most challenging circumstances.

Tech Help: Modern libraries have evolved to be community centers for access to technology and several have been able to continue this service even when their buildings were closed. As schools closed in response to the pandemic, some libraries have provided technical support for students who are new users or who are bringing technology into the home for the first time. Some libraries are also helping provide mobile hotspots for those without internet access, and plan to expand this kind of outreach and support after their buildings reopen. And some libraries are loaning out laptops to facilitate the switch to online learning.

Resurrecting Call Centers: Some libraries have discovered that some of their most vulnerable patrons, notably, the elderly and the poor, were less likely to be computer users and hence were more likely to be cut off from the library’s on-line services as well as from critical information. This led some libraries to develop or re-establish call centers, to provide dedicated phone access to library services.

Promoting The Arts During Lockdown: Some libraries have responded to the pandemic by beginning to publish zines featuring local art and writing, and plan to continue these creative endeavors in support of enlisting community members in local art and culture, after reopening.

Information Hub: Increasingly, libraries serve as a community information hub, serving as a primary clearing house for community information or stepping in to fill the gaps when normal channels are inaccessible. Many libraries have used the pandemic as an opportunity to assess how to optimize access to critical information, where the need is greatest and where gaps exist, and are working in collaboration with local governments to ensure effective access to critical information.

Expanding Collaborations: Libraries are increasingly working in partnership with townwide services. For example, in San Francisco, some public librarians have become part of the city’s response team for COVID-19 contact tracing. Libraries can become the hub for all kinds of citizen access to services (see e.g. descriptions for Los Angeles Public Libraries portrayed in Susan Orlean’s The Library Book).

Exploring Ways to Create Safe Civic Spaces: Public buildings are going to have to change in response to challenges posed by the pandemic. Libraries are now at the forefront of considering the challenges of creating safe civic spaces and of meeting new, demanding, health and safety guidelines in a post-pandemic world. Amherst Town Councilors Dorothy Pam and Steve Schreiber have noted that we are going to have to rethink the design of all of our buildings in light of this pandemic and national library organizations have already begun to brainstorm the challenge.

Mobile Services: I am reminded of a recent letter to The Indy by Alex Kent, asking the Town to consider investing in mobile library services, following the model of several other communities. Expanded ebook offerings and books by mail seem to be an obvious solution to getting the most books to the most people when the library is forced to close, but mobile services, currently absent in our own town, appear to be a cost effective way of taking the library to people who are mobility limited or who lack internet access and provide a flexible alternative when the building is inoperative.

Here in Amherst, our library is likely not our most pressing worry at the moment, as we tackle a protracted pandemic and an associated budget crisis. And yet, the library is a major planned expenditure for the Town and a cherished community institution. We would do well to discuss publicly and together, the kinds of challenges that the pandemic has thrown at us and the ways in which our library might be imagined/re-imagined to best serve us in the post-pandemic world that awaits us. I call on our town leaders to organize such conversations to marshal the collective vision and creative genius of the community. I would expect our town leaders to enthusiastically embrace the opportunity to openly discuss with residents what a post-pandemic Amherst (including its library) should look like and how the Town (and the Jones) can best be configured to meet the needs of Amherst residents during this pandemic and following this pandemic, and into a challenging future. But of course, we do not need to wait for someone to facilitate those discussions for us. We can all engage in a project of community visioning simply by raising questions and sharing ideas with our fellow Amherst residents. And so I encourage our readers to embrace this challenge and to share their ideas in The Indy.

Art Keene is Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at UMass. He coached girls cross country at Amherst High School for 17 years and was a Town Meeting member for 20+ years. He has lived in Amherst since 1982. He is a member of The Amherst Indy Editorial Collective.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made rethinking our Amherst community library — that is, the Jones, Munson Memorial, and North Amherst Libraries — imperative. When, if ever, will we again have Saturday events in the Jones Library that “draw upwards of 100 children” — plus, for the little ones, about one adult to each child? That 100+ child figure comes from the Library’s own promotional materials. I’ve personally counted as many as 80 happily squirming pre-schoolers at a Saturday children’s music program in the Library’s Woodbury Room. As the article above indicates, Amherst is not alone in suddenly having to rethink the whole enterprise of a community library. When, and how, will we start doing so?