OPINION: SCHOOLING AND LEARNING IN AMHERST AFTER THE PANDEMIC

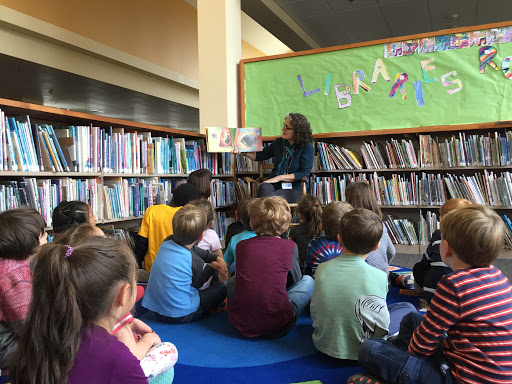

Elementary school class in school library in Amherst. Photo: arps.org

There may be two good things about this awful thing we are enduring right now. One is realizing that viruses like this coronavirus are not only possible or even likely but inevitable in the future. This has many implications for how we think about the future. The other thing is that it provides a clear and dramatic schism between before and after.

I want to think out loud about the “after” in Amherst’s approach to education before we try too hard to make it resemble the “before”. COVID 19, amidst its horrors, does give us a rare moment in which the future is necessarily detached from the past, and we can look anew at some of the unconscious attitudes and unquestioned assumptions that undergird our thinking about schooling and learning. (The terms “unconscious attitudes” and “unquestioned assumptions” are from historian Thomas Mendenhall, former president of Smith College in an era when such attitudes and assumptions nearly always resulted in women’s colleges being led by men.)

Fifty years ago I had the privilege of becoming the principal of Mark’s Meadow School in North Amherst. I was there for twenty-one years, and the privilege was being part of an extraordinary staff whose willingness to try out ideas was exceeded only by their love and commitment to children and families.. Most of what I think I know about education I learned at Mark’s Meadow, Thirty years ago I wrote an article entitled “Thinking About Schools: Five Uncomfortable Ideas,” in which I tried to address what I learned from those years at Mark’s Meadow.

It strikes me that now, as the community is thinking about how to reopen its schools, might be a time for it to look anew at those assumptions and attitudes. So here are the five that I identified thirty years ago. I mention them briefly here but can expand on them in future Indy commentaries if there is interest. It would be wonderful if others would add to the list of uncomfortable ideas that we should examine, and perhaps re-think, about the way our children grow and learn.

1. Schools overprize conformity. Even as our schools increasingly address thinking about diversity of background, race, ethnicity, and wealth, they (we) haven’t begun to imagine dealing with diversity of learning styles, rates, and interests. When, in 1983, Howard Gardner advanced the idea of multiple intelligences, it attracted widespread attention everywhere but in the education establishment. In a diverse society there is nothing that everybody needs to know; no skill that everybody needs to have. The organization of classroom, curriculum, and assessment is based on the notions of age-appropriate and grade-appropriate norms. Neither of these is learning-appropriate. Norms belong to the world of testing, not the world of learning. If we truly put learning first, both our school buildings and our curriculums would be very different indeed.

2. Schools overprize right answers. Right answers exist of course, and they are important. But they are less important in life than they are in schools. Much, perhaps even most, of life is lived under conditions of uncertainty, probability, and paradox.The realm of right answers creates a world picture that is manifestly unhelpful, and, as we have seen throughout history, dangerous. The right answers prized by schools prize are too often those offered by teachers, textbooks, and traditions. In other words, authorities. Learning under conditions of uncertainty should be a major interest in curriculum makers, teachers, and boards of education.

3. Schools overprize reason and undervalue imagination. Most children have active imaginations until about halfway through the second grade, when reading, writing, and worksheets, rather than play, become the central manners of learning. The teachers of young children in Reggio Emilia, Italy, present children with provocations which form the basis of intense and creative group problem-solving. When we tried it at Mark’s Meadow in the ‘80s, we discovered that 5-year-olds are capable of astonishing and profound insights if they are not too soon burdened with what schools call scientific inquiry. Successful techniques, both mental and physical, are grounded in hunches, trial-and-error, and “what ifs.” Science Fairs have long been evidence of this in schools, and the same sort of imaginative problem solving can be used in all areas of school-based learning. Restore intuition to a central place in learning.

4. Schools overprize a direct connection between teaching and learning. Much — perhaps most — of what is learned in school is not taught. Much — perhaps most — of what is taught in schools is not learned, or at least not integrated into a world picture that means it will be remembered and used as a building-block of understanding. Both curriculums and syllabuses are organized to facilitate teaching. They reflect organized and coherent world pictures that they wish to inculcate in students. But students also have organized and coherent world pictures unlike the curriculum’s. The best teachers know that they have to pretend not knowing what they think they know and, instead, imagine what their students think they know. This meshing of world pictures reflects the truly collaborative relationship between teaching and learning. Besides, what children mostly learn from their teachers is how to be an adult.

5. Schools overprize the idea of progress. Real learning is creating changeable world pictures that give pride of place to paradox over progress. Here are some central paradoxes that I think are true of the world and ought, therefore, be central to schooling and learning.

Whole and Part

Knowledge and Belief

Self and Other

Life and Death

All of these dualities both embrace and repel one another. Every thing, person, idea is simultaneously a whole and a part. Knowledge is both based on and antagonistic to belief. We are always both self and other. Living and dying are two names for the same process. And of course there are many other paradoxical conditions and situations that reveal themselves if we are prepared to notice them.

I believed these things thirty years ago and I believe them today. Moreover, I look at this moment in Amherst’s history as a rare opportunity to heal the sores that so changed our communal lives when, because we all felt so intently but differently about our town’s schools, we stopped talking to one another. Looking at our unconscious attitudes and unquestioned assumptions about schooling and learning might create breathtaking possibilities as Amherst confronts its post-COVID brave new world.

6. Schools overprize [my spell-checker wants to change this to “overprice”] being “in school.” Connecting directly with the natural world, especially for the youngest kids, is essential. Why aren’t our “schools” – at least some of the time –located on farms, in parks, or out “in the real world”? There are many examples, ranging from “outdoor” schools in Oregon to the Miquon School in Pennsylvania – for more examples, please see:

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/31/fashion/outdoor-preschool-in-nature.html

[I’d enjoy hearing Michael’s – and everyone’s – thoughts on this suggestion, Rob]

I thank Rob Kusner for his suggestion. Actually, back in the 70s, Amherst Elementary students shared a wilderness camp setting with their teachers for a week, I think. And I think it was 4th grade, although if anyone else remembers it differently I will stand corrected. It didn’t last too long, for both financial and logistical reasons. But Amherst schools could easily incorporate more of the outdoors into their students’ curriculum without great cost. And more of the town. Just before I came to Amherst in 1970 I was engaged with others in starting a “school without walls” for the Chicago Public Schools, as part of their integration efforts. Metro High School had no building of its own; its program took place in business, cultural, religious and public institutional settings. It was successful for quite a few years.

It would be wonderful, although probably naive, to think that Amherst might think about alternative ways of conducting its elementary curriculum that didn’t require the community to build – and pay for – a new school. Schools as we know them (and experienced them ourselves) really have as their central mission the control of children. Education is only their second priority (or possibly third, after ranking children). I can understand and appreciate this; adults have to get on with their lives, and they want their children to be safe. Moreover, these days it is probably better for children to be in school than in front of screens for six hours a day. The experience of having schools closed for the past three months may help us focus on the internal organization of schooling and curriculum and encourage the organization of local settings outside of school buildings that can be incorporated into them. Both Groff Park and Mill River Park could easily be re-thought to provide more opportunities for both learning and adventure.

Reading this piece makes me want to be a student in an elementary school where Michael Greenebaum is principal. There is opportunity in this moment.

First – thanks to Michael for getting this conversation started. Coming out of the pandemic (and perhaps anticipating the next wave) we are going to face no small number of challenges concerning how we go about organizing education. It’s a great opportunity to re-think all of our educational needs and priorities. I have been thinking a lot about this and also talking about it with family members who are educators. I have a lot on my mind and I imagine I will turn those thoughts into a column in the coming weeks.

So much of the discussion about reopening the schools has been focused on logistics – e.g. how will we manage safe social distancing. And rightly so. But I am interested in having us think about how we can use this moment to truly reimagine public education and not just return us to some semblance of stability. But here are four of the big ideas that I’ve been talking to others about- things I’d like to change.

1. Education for Independent Inquiry – so many kids are struggling with distance learning and home schooling right now and this could be partially ameliorated by preparing kids to be independent learners. This is not a new idea at all and goes back to some of the earlier American educational theorists like Dewey. The goal of preparing independent learners was greatly undermined by the testing and standardization movements. And there are plenty of good reasons to do this besides preparing for the next quarantine.

2. Teaching for Black Lives – Anyone notice what’s going on in all fifty states right now? It might lead us to ask, how has education prepared our kids for this moment? How can we insure that our children are educated in a way that leads them to create and sustain a just society? How do we insure that our kids are prepared to be the solution for what ails our nation right now? These questions ought to be central to any reimagining of post-pandemic education.

3. Education inequities – the pandemic has revealed (and is also a result of ) deeply entrenched inequities in our society. Now is the time for us to address those inequities including those in the educational system (especially since most public school systems are going to be hit with post-pandemic austerity budgets) and also create curriculum and pedagogy that subverts those inequities.

4. There’s been much written about how the pandemic has produced considerable emotional stress for kids for all kinds of reasons. And so it would be useful to consider how we prioritize curricula and pedagogies that address the emotional well being of children when they return to the classroom.