Letter: ARPS & APEA Are Erecting Barriers To Education

Photo: flckr.com

When will Amherst Regional Public Schools (ARPS) students return to the classroom? On September 11, Superintendent Dr. Michael Morris announced a tentative agreement between the District and Amherst Pelham Education Association (APEA) that creates a barrier to education for our students. The tentative plan is inequitable and discriminatory.

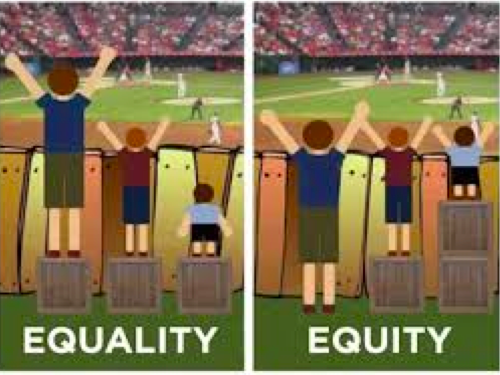

The District has been using the following three words “Access, Participation, Benefit” and visual (below) to define equity. The tentative agreement conflicts with the District’s visual rendition of equity. Under the tentative agreement, as of Oct. 1s a small portion of our students are standing on a tall box experiencing the game while all other students are at home watching the game on TV. On October 19, some additional students will experience the game in person. Then months later, perhaps February 2021, all students would attend a few innings in person. If the District honors its definition of equity, the District will remove barriers to attendance. Denying in-person instruction for SOME students is creating a barrier to learning unnecessarily. Our community schools should be dismantling barriers, not erecting them.

In addition, the current plan violates the District’s policy on discrimination. As found in their policies and procedures “The Districts do not discriminate on the basis of race, national origin, age, religion, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, economic status, political party, or disability in admission to, access to, employment in, or treatment by its programs and activities. The Districts’ policy of nondiscrimination extends to students, staff, and the public with whom it does business.” Directly contradicting this policy, the tentative plan discriminates amongst students based on age (grades) and perceived economic status.

Under the metrics in the tentative plan (see below), my children would be denied all in-person instruction until November 16. After that date, they would be denied in-person instruction 4 out of every 5 days until possibly February, after which they would only be denied 3 out of every 5 days of in-person instruction. It is also possible my teenagers won’t receive the valuable in-person instruction by teachers or benefit from peer socialization, key components of public education, the entire academic year.

Are we willing to accept inequity, barriers to education, and discrimination and fail our next generation? With our current metrics in the district at 10 new cases/100,000 and well below a 2.5% positive test rate, we are far below the transmission metrics outlined in the tentative agreement. Therefore, grades 7-12 should begin in-ani hinstruction along with all other students on October 1. If current negotiations don’t allow for such flexibility, at a minimum we should revert to the previously approved Aug. 6, plan.

In a community that prides itself on equity (the Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary defines it as “freedom from bias or favoritism”), why are we allowing the APEA and the District to create barriers to education and discriminate against our students based on their age and their economic status? As a community and as caregivers, our children deserve equity in education, not barriers, and equal access for all.

Health metrics in September 11 announced tentative plan:

- fewer than 28 new cases/100,000 using 7-day rolling average in three counties with weightings of .8 for Hampshire County, .1 for Franklin County, and .1 for Hampden county AND

- a positive test rate of <2.5% for the same counties and weightings using a 14-day rolling average

Stephanie S. Hockman

Stephanie S. Hockman is a resident of Amherst

By the same reasoning, shouldn’t teachers and staff who are at higher risk of contracting COVID19 and suffering serious consequences – including permanent disability or death – be allowed and encouraged to continue all-remote teaching until safe and effective vaccines are administered to all the students?

Asked more bluntly: should one person’s “equity” be another person’s “death-sentence”?

Yes, we live in a country that has freedoms. If there are teachers at risk or even families that want to elect to have their children learn remotely, they have that right. I am by no means stating there is a “death-sentence”. That’s sensationalizing this. What I’m saying is that everyone should have the freedom to choose the education they have a right to receive, but those that want in-person instruction and in-person classmate interaction to allow for learning are not given that freedom of choice; for many until Nov. 16th.

Giving everybody the choice to do whatever they want — some remote, some in-person — is completely unrealistic for teachers. It’s challenging to teach in a classroom, let alone with all the physical distancing etc in place. It’s also challenging to teach remotely. To do both at the same time is just not workable. To switch from one to the other mid-stream involves transition time, at best, and lack of preparation for one or the other mode.

Administrators around the country want to be able to say “yes” to parents, and so they get to these places where they say “yes we’ll do hybrid,” “yes parents can choose”. But that is not leadership. There’s no meaningful choice of all options.

Administrators need to be able to show leadership and say what is and is not workable, and then do what is needed to make the workable solutions equitable. Catering to fantasies of parent choice is not workable.

Laura – I respectfully disagree. Choice is a freedom we have and I don’t believe this is unrealistic for teachers. We are seeing many teachers across MA and the US doing just this. I’ve seen simultaneous remote/in-person instruction in public schools and private schools across this state. I appreciate that it is hard, but I have faith in the teachers in our District. they are amazing!

As a university professor and research mathematician, I’d love to be back in the classroom teaching my students, and back in the seminar rooms brainstorming with my colleagues about new and on-going projects.

However, thanks to wise decisions reached between university administrators and our faculty representatives, I’m now working remotely: spending a great deal of time (a lot more time than I ever did lecturing!) preparing video lectures for my students to watch before our many hours of Zoom meetings (where we discuss homework problems or other interesting ways to think about the material – inter alia, this involves much interrogation by me, followed by their many “Zoom private chat” responses); the result is a “flipped class” model for learning that took many months of experimentation last spring (when we abruptly “pivoted” to “remote instruction”) and over the summer to develop (and it’s still “under construction”).

And I’m also Zooming now with many colleagues all over the world to collaborate on the aforementioned research projects (it saves a lot of car, train and airplane trips, but it’s not the same as “being there”). But (aside from growing some of my own food, and posting a few pointed comments to The Indy or The NYTimes ;-), most of my time is devoted to this professional work – if I’m getting 40 hours of sleep per week, I’m lucky – so I guess I now have a “flipped life” too!

Would I wish this sort of work week on any Amherst school teacher? Of course not, though, before the COVID19 pandemic, the many teachers I know were already putting in as much time on their teaching out of school as they do in school. The extra effort now needed to remote-teach should earn them extra salary, while expecting them to perform the hybrid-model acrobatics should count for at least triple-time – if it weren’t a violation of labor laws (those laws don’t seem to apply to us professors ;-)!

So I respectfully suggest that the expressed expectations for our teachers *are* unrealistic – they are also unfair, and are potentially dangerous to many teachers and staff for whom the real risk of serious illness (or even death) is unacceptable.

Let me conclude with a historical coda, along with some sincere advice:

During the 17th century, Isaac Newton quarantined on a farm for several years while the bubonic plague pandemic ravaged Europe. We have his “prudent pause from the usual way of business” to thank for sparking a revolution in mathematical and scientific thinking.

Let’s not rely on “authority” or “faith” alone to get us through this pandemic.

Instead, let’s be prudent: our public schools can re-open for in-person learning when there’s a safe and effective vaccine for all the students (and anyone else who would benefit). Until then, all-remote-learning model (hopefully with the cooperation of our thoughtful and engaged parents and guardians) is the way to go.