Culture Club: The Problem with Zappa

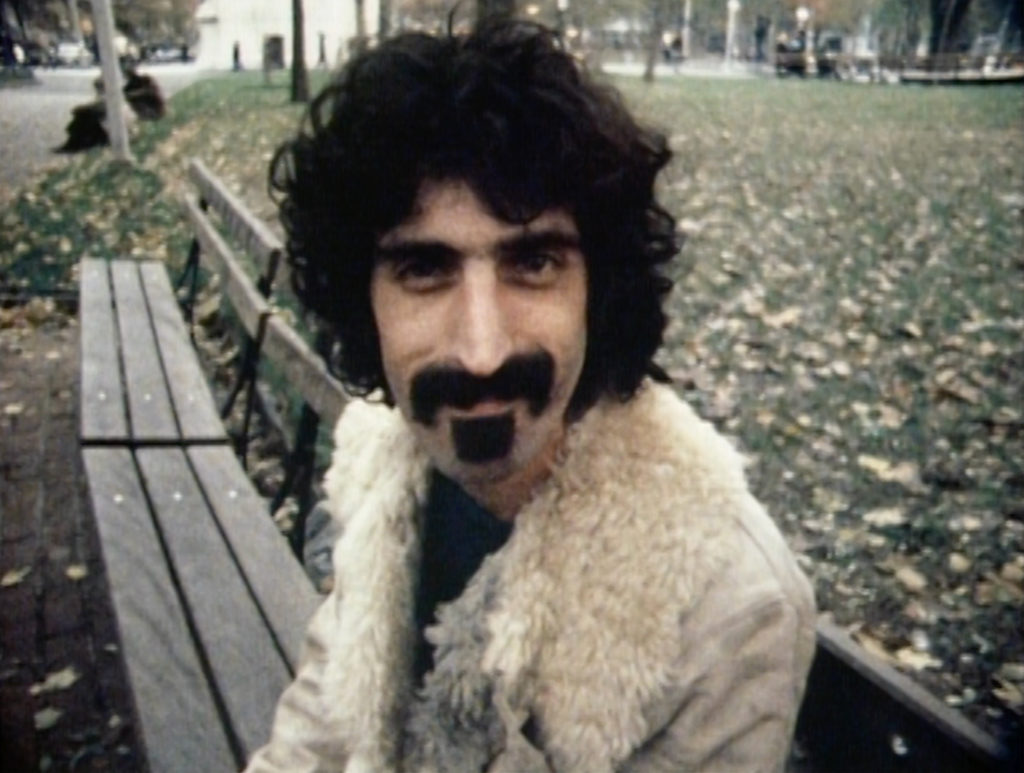

Frank Zappa: Photo: Roelof Kiers. courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

The problem with Zappa, the first authorized documentary on musician Frank Zappa, who died of cancer in 1993, is that it doesn’t dig deeply enough into his foibles. Amherst Cinema recently screened the film as part of its streaming program and it’s currently available on Amazon Prime. While Zappa only hints at the complex, often troubling, personality of both the man and his music, treats abound.

Zappa is filled with never-before-seen footage drawn from his archives and features extensive interviews with his wife, Gail, who rarely spoke in public. There’s footage of a young Captain Beefheart resplendent with a greaser quiff. Animator Bruce Bickford, who directed phantasmagorical music videos, sculpts a Zappa homunculus for the camera. Zappa’s first successful band, The Mothers of Invention, is seen performing during its notorious 1967 residency in New York City. Zappa appears with the original cast of Saturday Night Live in skit and song. Most remarkably, he’s shown at 16, playing with the Blackouts, a racially mixed rhythm ‘n blues group whose presence in small-town California during the 1950s was taken, he remarks, as “a threat to the decency of the community.”

One of the documentary’s leitmotifs is that Zappa spent his career pushing the boundaries of decency. Inspired by Lenny Bruce and Mad Magazine, Zappa’s music continually flirted with obscenity. During the 1980s, he was the only major musician to speak out against the Parents Music Resource Center’s attempt to censor music lyrics. Zappa shows him practically coming to blows with a conservative reporter during a PBS debate about censorship. It ignores the misogyny and homophobia in Zappa’s own lyrics and performances. Songs like “Easy Meat” and “Crew Slut” are especially difficult to listen to today. The film also leaves out a segment of the same PBS interview where Zappa declares himself a political conservative.

Zappa doesn’t entirely shy away from its hero’s shortcomings. In an old interview, Zappa describes the many affairs that he had while touring when he would “strap on a bunch of girls.” Gail responds to this by remarking that their marriage lasted because she stopped talking to her husband about his infidelities. “Frank does what he does, and I do what I do,” she says. What she did, as can be seen in the documentary, was manage his business affairs with the same dedication that he put into making music.

The primary view that the documentary reinforces is that, despite being known as a guitar God, Zappa’s life-long ambition was to be taken seriously as a composer, from his precocious obsession with Edgar Varese through the performance, just before his death, of The Yellow Shark, a musical suite for 18-piece orchestra. But Zappa truly excelled when he was neither striving for legitimacy nor kicking against the pricks. His best work came when he abandoned musical genres and carved out his own weird niche by mixing doo-wop with Stravinsky, the Goldberg Variations with Guitar Slim, or Charlie Parker with psychedelia.

Zappa ends with a fittingly elegiac performance of “Watermelon in Easter Hay,” one of his favorites. Over a minimalist percussion loop he plays an achingly wistful guitar solo that ends in an uncomfortably noisy place. Although enjoyable, Zappa would have benefited from telling a little less of the story of the great composer and focusing more on how unsettling Zappa and his music could be, no matter how much that might upset the image of his genius.

William Kaizen is an art historian and public art advocate. He chairs the Amherst Public Art Commission.

Such a rich review! Despite the film’s shortcomings, I’m eager to see it (and support Amherst Cinema).