Culture Club: Girls Against God

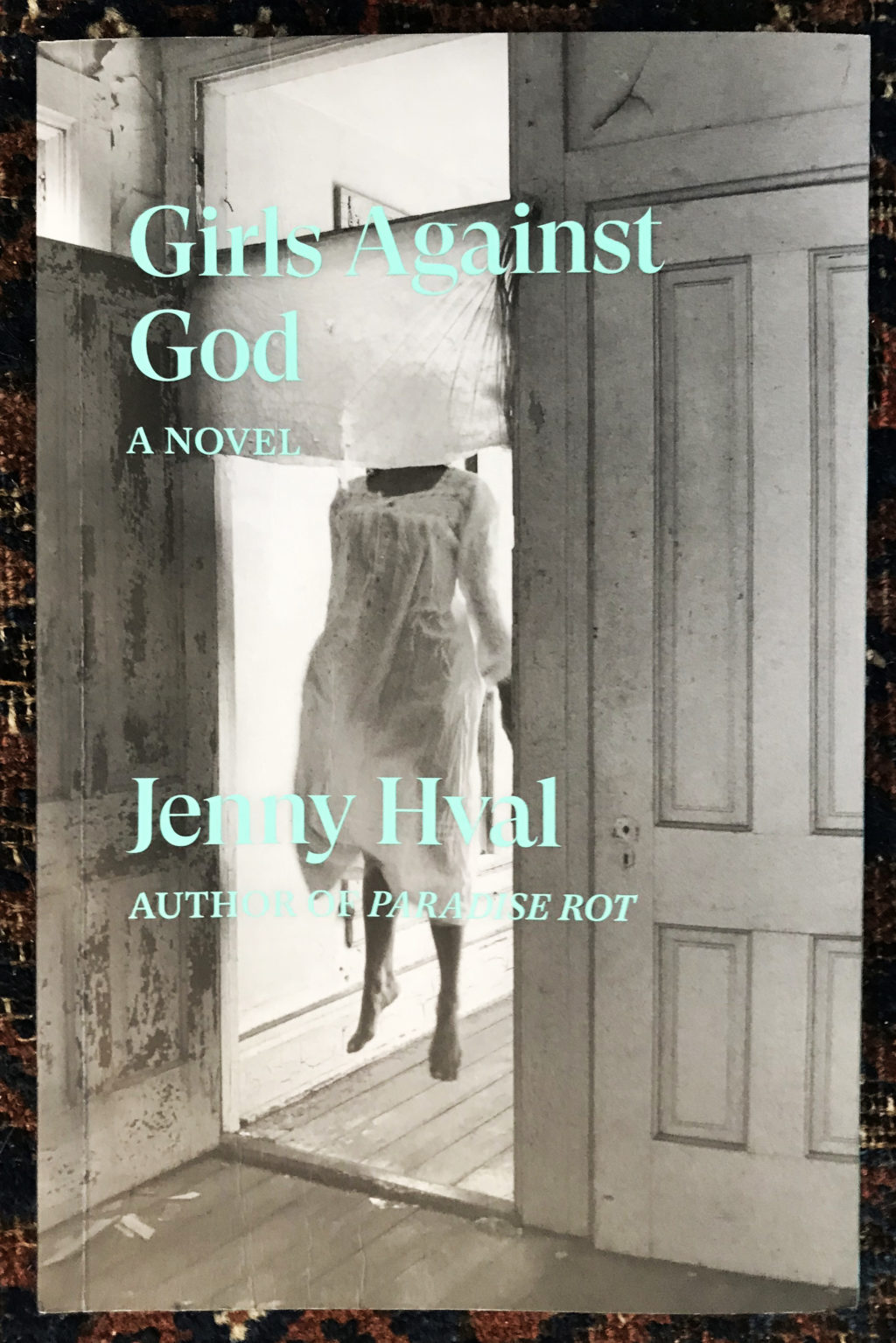

Cover, Girls Against God by Jenny Hval. Photo: William Kaizen

Witches aren’t what they used to be. Nowadays witches are even embraced by the U.S. military. In recent decades, the Department of Veterans Affairs added pentacles to its list of approved religious symbols for headstones and the Air Force has built an $80,000 outdoor shrine for pagan worship.

The thoroughly modern witches in Jenny Hval’s recently translated novel Girls against God fly neither broomsticks nor fighter jets. They do, however, cast spells via cellphone and fancy themselves filmmakers.

The original Norwegian title of Hval’s novel was To Hate God. “I hate God,” rails the book’s unnamed protagonist in its opening line, by which she really means that she hates the stifling, Christian atmosphere of “southern Norway’s white Scandinavian paradise.” She hates being a girl told to smile and be less grumpy. She hates being lonely. She loves black metal. We follow her from teen gothdom to film school in New England. She settles in Oslo and falls in with like-minded friends with whom she forms a coven.

Girls against God is a string of surreal set pieces. Short chapters are punctuated with even shorter “episodes” that read like music video scripts. It culminates in a longer, plot-driven film script about a metal dude lost in the woods who births, amidst the coven, a mysterious egg. Hval is better known as a musician than as an author and the book’s most expressive passages come when her characters commune through music or art.

Hval describes the coven’s witchcraft as an artform both ancient and contemporary. Her witches are a performance art troupe intent on cursing society, like a less political Pussy Riot.

Hval frequently punctures the book’s air of gothic horror with technologically driven absurdity. The coven infests the city’s electrical network so that it gives off a stench that “smells like rotten milk and wet dog.” They break into a museum and make a 3D printed Ikea vase that looks like “a Scandinavian reproduction monster.” After inserting themselves into a scene in a girl’s college cafeteria as if it were a paused video, they hold a sabbath where they summon demons made of spaghetti and chocolate. They use “the cosmic internet” as their main tool for witchcraft, scrolling ever downward through sinister image searches. “In the end,” says the protagonist, “I’ll be able to scroll myself all the way to hell.”

While I doubt the witches in Girls against God would join the military, the protagonist notes that to hate is to fight for a better future. “Hatred and hope will continue to chime together and curse the world,” she says. “What’s most important about magic is to create meeting places, so that later, others can stretch further into this artistic space.” Hval’s witches are not interested in being included in existing social institutions. They create new opportunities for those who are excluded to revel in their shared exclusion. Her witches are thoroughly modern not because they harness technology, but because, with a devil-may-care spirit of adventure, they conjure weird, new spaces where women like themselves can play and make art.

Girls against God makes especially good bedtime reading. Read it on an electronic device so that the techno-witchery it depicts bleeds over from real life into your dreams. Instead of being dropped into the pit, you’ll be borne aloft by the compulsive page scrolling it elicits.

Culture Club is a column that will fill out the Indy’s news and opinion coverage with discussions of all things related to cultural affairs in Amherst. It takes the word “culture” most broadly, to mean all the arts of all stripes, from literature and poetry to visual arts, dance, and theater. Potential columns will range from updates on cultural events in town to reviews of TV shows, exhibitions, records, and anything else related to the arts and humanities that seems especially noteworthy. Please send me suggestions for future columns at wkaizen@gmail.com.

William Kaizen is an art historian and public art advocate. He chairs the Amherst Public Art Commission.