Culture Club: Notes On Miles Davis’ Double Image

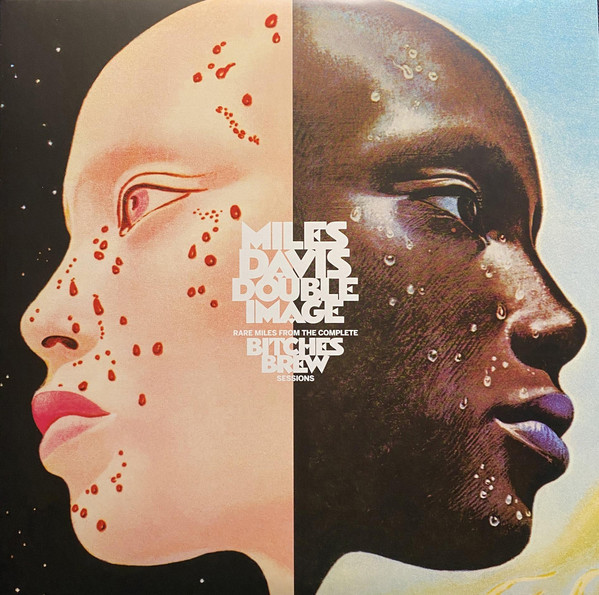

Album cover for Double Image by Miles Davis. Photo: William Kaizen

Although it seems hard to believe now that Kind of Blue is enshrined as the bestselling jazz record of all time, Miles Davis career went into steep decline in the years following its release. By the late 1960s, jazz had been eclipsed by rock and soul, and he was playing to as few as 30 people a night. After attending a concert by Sly and the Family Stone and learning how much money they were making, he decided it was time for a change.

At age 43, Davis made one of the most startling re-inventions in the history of popular music. He began opening for the Grateful Dead and Carlos Santana and released a torrent of albums featuring electric instrumentation that have become some of the most influential of his long career. The recently released double LP Double Image: Rare Miles from the Complete Bitches Brew Sessions catches Miles in the midst of this transformation.

Jazz purists bemoaned Davis’ turn to electric music when Bitches Brew was released, calling him a sell-out, but rocks fans loved it. It sold 400,000 copies in its first year, becoming the top-selling jazz album up to that point. As the adulation from young, non-jazz fans began to roll in, Davis joked that he was happy to have sold out. He had never earned so much money from his music before, and he was happy to be reaching new audiences.

Bitches Brew is a strange hit record. It features as many as 13 musicians playing together, including two full-kit drummers, miscellaneous other percussion and three electric pianos, who weave dense clouds of sound that Davis pierces with echoing, electronically processed trumpet blasts.

Double Image features outtakes from the sessions immediately following Bitches Brew. The songs have a sparer sound that leans heavier on funk, although most are more pastoral than his later funk-influenced work. Davis began adding Brazilian and Indian instrumentation to a number of the songs, which he would continue to use through the seventies, laying the groundwork for world music as much as jazz rock.

Side A begins with “Yaphet,” a slinky, psychedelic samba with sitar playing high and moaning guica on the bottom. “Corrado,” which follows, is a slow jam that starts with drum rolls and crashing cymbals on the one, eventually resolving into a sinuous duet between Davis’ trumpet and the bass clarinet.

Side B has two versions of “The Little Blue Frog.” On the master take, which comes first, the guica creates a croaking pulse complemented by jagged guitar lines over which Miles adds melodic color. On the alternate take, which is the highlight of the album, the bass line is funkier, the guitar groovier, and the keyboards more soulful than just about any other song Davis recorded. His slow, bluesy solo sits deep in the pocket over some of the most syncopated funk in his catalog.

Double Image ends with “Recollections,” another strong outtake. Shaped like a sunrise, it moseys along quietly, sounding like the moments before dawn, with weird, bird-like keyboard fills punctuating cyclical, muted trumpet lines. About ten minutes in, the band crescendos and Davis’ horn beams with light, triumphantly clear, as if the sun has broken above the horizon.

After the Double Image sessions, Davis would become a bigger star than ever before. He went on to headline stadiums while the musicians who played with him on these sessions (including Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, and John McLaughlin) went on to form their own stadium headlining fusion bands. This was the last time that Miles would be accompanied by such an impressive cast of jazz heavyweights, whom he pushed to play beyond their previous abilities by forcing them out of their comfort zones and into the weird hybrid music he pioneering.

The songs on Double Image are well curated and the set worth owning, not only for its beautiful packaging which adapts the original album’s surreal afrofuturist cover art, but to have “The Little Blue Frog (Alt)” and “Recollections” on vinyl, which sound amazing. If you can’t find the vinyl, you can listen on YouTube. While you’re at it, check out the new PBS documentary on Davis, The Birth of the Cool, which gives a full account of Davis life, including his electric work, which other documentaries such as Ken Burn’s Jazz have ignored.

Culture Club is a column that will fill out the Indy’s news and opinion coverage with discussions of all things related to cultural affairs in Amherst. It takes the word “culture” most broadly, to mean all the arts of all stripes, from literature and poetry to visual arts, dance, and theater. Potential columns will range from updates on cultural events in town to reviews of TV shows, exhibitions, records, and anything else related to the arts and humanities that seems especially noteworthy. Please send me suggestions for future columns at wkaizen@gmail.com.

William Kaizen is an art historian and public art advocate. He chairs the Amherst Public Art Commission.

A while since I read this, but every time I encounter it, while working on the Indy, I remember Pearl Cleage’s essay, “Mad at Miles”. I read it in Deals with the Devil, and Other Reasons to Riot. When we truck with artists on artistic merit, then I believe we ought also truck with their truths as people. Sadly out of print, but worth checking out at used bookstores or the library: