Almanac: Close Encounters Of The Possum Kind

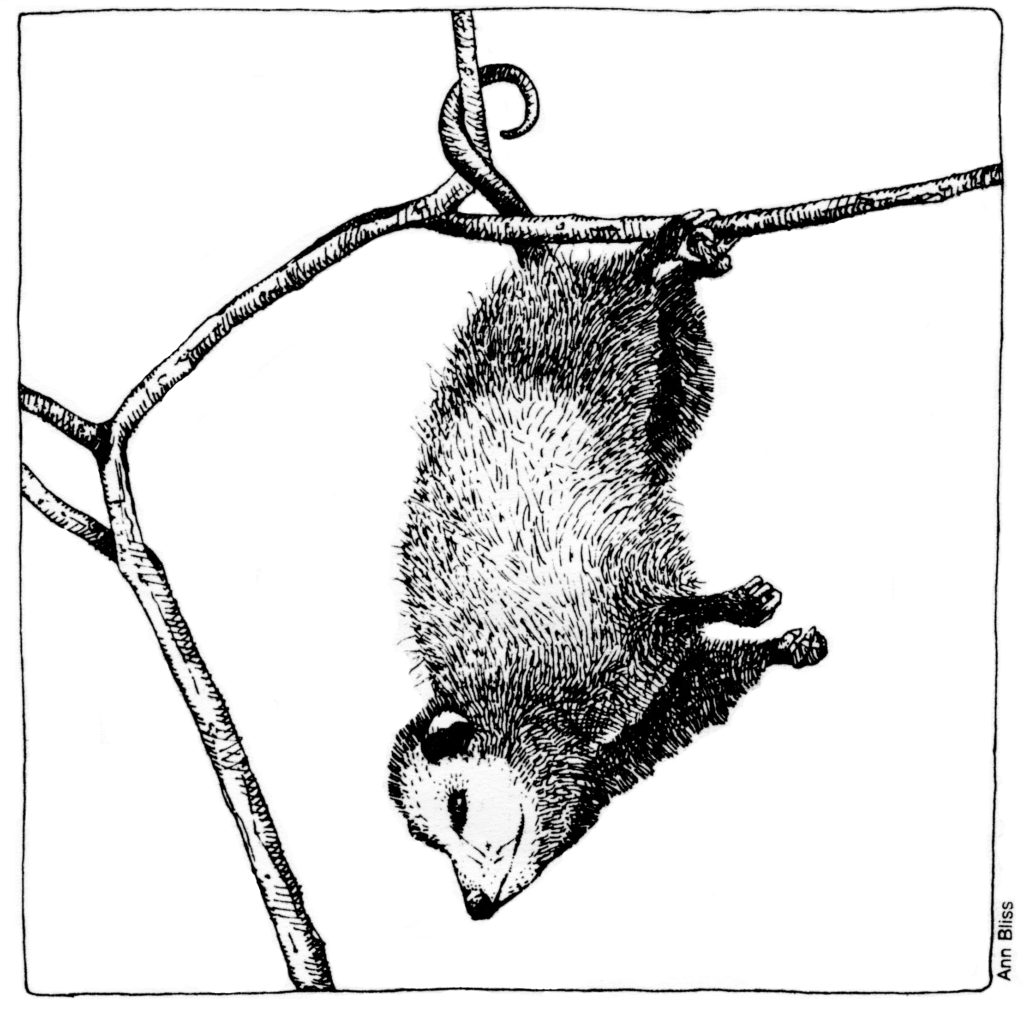

Illustration: Ann Bliss

I went out to water the chickens in my friend’s chicken yard the other evening. She’s got a coop—the tiny house where the hens roost and lay–and an adjacent fenced-and-roofed yard where they can safely eat, drink, scratch around, and cavort.

It was dark and I was inside the yard when a movement in the shadows startled me. It was an impressively large opossum, with long pointed snout, pale face, thick naked tail, and a bushy body the size of a large house cat. How it got in, we still haven’t figured out, but however it managed, it seemed incapable of finding its way out again. We stared at each other a moment. An opossum is hardly a mountain lion, but I was in no mood to tangle with a cornered animal that did, after all, possess a healthy set of teeth, including prominent canines.

“Listen,” I said. “Let’s make this easy. I’m going to walk away from the door, and you’re going to use it to get the hell out of here, OK?”

For some reason the creature did not seem to comprehend this simple plan. It started scrabbling at the fencing in a futile attempt to climb. So I edged toward it from the side, shooing it verbally and with gesticulations, toward the door. It backed off, looked momentarily confused, then finally connected the dots and made a run for it.

In retrospect, I’m a little disappointed the intruder didn’t find me threatening enough to pull the classic opossum trick of feigning death (“playing possum”). I always thought that was an exceptionally stupid survival strategy since, after all, the goal of foxes, dogs, and other possum predators is a dead possum. But I would have been interested to witness it.

Looking into the matter a little bit, I learned that possums aren’t actually playing dead—they’re playing “I’m- sick-and-weird-and-probably-bad-for-you.” When really threatened (i.e., by more than a gesticulating human being) a possum flops down with its lips drawn back, teeth bared in a ghoulish grimace, saliva foaming its mouth, and with a foul-smelling fluid oozing from its anal glands. Faced with this disquieting transformation, most predators will poke and prod the possum a bit and then leave. Within about 10 minutes the animal regains its normal composure and goes on its merry way.

Unfortunately, all of the dead-looking possums I’ve ever seen really have been dead– flattened by some vehicle or another. I feel sorry for possums that way. The poor things literally don’t have the smarts not to play in the street. Opossum brains are about six times smaller than the similar-sized raccoon. And I’ve yet to read a report by anyone who has worked with the animals that doesn’t mention their dim-wittedness. As omnivores, they are also attracted to carrion, which, more often than not, is located on the very roads that transform live healthy possums into the carrion they were hoping to feast on.

Clearly, however, brains are not everything, because possums are an extremely successful family of animals with many dozen species thriving worldwide. Our possums, technically, Virginia opossums, are the only species of marsupial living north of the Rio Grande. Marsupials are named for their pouch, or marsupium, into which the radically premature young must find their way after they are born, which is typically only about 13 days after conception. (Possum conception, as with other marsupials, features an interesting anatomical twist: males insert their two-headed penis into the twin vaginas of the females, and the babies are born from two uteruses.)

At birth the embryonic young are no larger than a pencil eraser. Nonetheless, the helpless little things have to squirm their way, blind and deaf, to their mothers’ marsupium. There they find a teat and grab hold for dear life. The teat swells a bit inside the baby’s mouth forming a secure attachment maintained for 50-65 days. When the young first clamber out of the pouch, they cling to their mother’s coarse fur. They have to hang on tight because if they fall off, mom is likely not to notice.

Possums are the only North American animal capable of supporting their entire weight by their tail, making them the only truly prehensile animals we’ve got. That naked tail however, isn’t a brilliant feature in the northern parts of the animal’s range—meaning New England and up to southern Canada. Its tail and hairless ears are vulnerable to freezing. It’s not uncommon to see possums missing the tips of their tails or with ears scarred by frostbite.

These disadvantages, and their less-than-genius intellectual abilities, are more than offset by the possum’s flexibility. They will eat nearly anything, dead or alive, and can nest in a wide range of places, including under human dwellings. Although possums are still hunted for their meat in some rural areas, humans, for the most part, have helped the species by reducing predators and introducing new food supplies, such as garbage, compost piles, and inadequately-secured chicken coops (they’re after the eggs, not the chickens themselves).

So here’s to the lowly possum! As Mr. Spock would say, “Live long and prosper.” But please leave the chicken eggs alone.

Almanac is a regular Indy column of observations, musings, and occasional harangues related to the woods, waters, mountains, and skies of the Pioneer Valley. Stephen Braun has a background in natural resources conservation, which mostly means he is continually baffled by what he sees on explorations of local natural areas. Please feel free to comment on posts and add your own experiences or observations. You can also email at: braun.writer@gmail.com.

And possums rarely get rabies due their low body temperature. They also like to eat Ticks, which makes them heroes in my book.

Almanac is my favorite column! I love Steve’s charming writing style.

Oh, yes…thanks for mentioning the tick diet thing Maura. I meant to mention that. Possums are said to eat roughly 5000 ticks a season. Not all of those are the Lyme-disease-spreading deer ticks, but a lot must be, so I’m with you…go possums! I’ve had Lyme twice, neither time serious, but ticks are really pesky around here.

Almanac: always worth reading!

And always worth a comment: one trait I’ve observed in this nocturnal North American marsupial is their regular route, running almost like a Swiss railroad; I’ve seen this in urban Berkeley, CA, during the 1980s, and more recently in rural Birchrunville, PA.

Have other readers noticed this type of possum punctuality too?