Culture Club: Circling The Zero

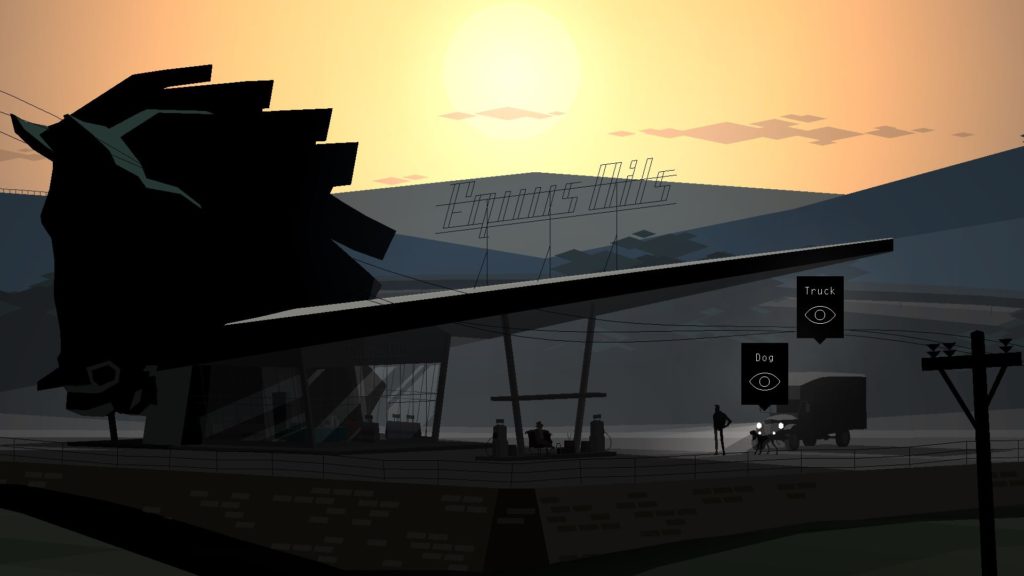

Equus Oils, where you journey begins. Photo: Screen shot, Kentucky Route Zero

Thanks to COVID, it’s been more than a year since I’ve visited a museum in person, which is an eternity for an art lover. Stuck in the Pioneer Valley where galleries have been shuttered, I’ve had to settle for virtual exhibitions instead. I recently visited Limits and Demonstrations, an online retrospective of Lula Chamberlain’s work. The small but powerful exhibition makes savvy references to the history of media art, with nods to Nam June Paik and Racter, the first artificial intelligence to write a book of poetry. I was duly impressed with the ways that Chamberlain cleverly pushes the limits of the Unity videogame engine that she uses to create her work. I was even more impressed that she wasn’t a real person.

Along the Zero

Chamberlain is a character in the magical-realist story Kentucky Route Zero, an interactive fiction made by Cardboard Computer, a collaboration of Jake Elliott, Tamas Kemenczy, and Ben Babbitt.

Although Kentucky Route Zero is available on videogame platforms including Steam for a nominal fee, it isn’t a game. There’s no fighting or shooting, no winning or losing. Adapted from the earliest text-based adventure games, it’s more like a participatory play where you guide characters through various stage-like spaces and select from lines of dialog and other text that appears in speech bubbles. The text reveals relationships and uncovers backstory, motivating further action. The choices you’re presented with have different emotional tones, allowing you shape the tenor of the story without restricting your ability to get through it.

Cardboard Computer released Kentucky Route Zero in installments between 2013 and 2020 as each of its five acts was completed. Given how good an exhibition it is, it is remarkable that Limits and Demonstrations is but an interlude that they had originally designed to help determine if a user’s computer graphics card was powerful enough to load the main story. Seven years later, the technology needed to run Kentucky Route Zero has become commonplace and the story its makers set out to tell has grown into one of the most powerful experiences available in a work of new media art. Although Elliott cites William Faulkner and the American tragic playwrights as touchstones (O’Neill, Williams), it’s more of a mash-up of The Grapes of Wrath and an Appalachian folktale. A quirky sense of humor akin to Northern Exposure or Twin Peaks punctuates its self-seriousness to good effect.

Written in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, Kentucky Route Zero tells the story of Conway, an alcoholic delivery man, who loses his way looking for the house that is his final delivery before retiring. The house is at the other end of the Zero, an underground highway that mysteriously traverses a vast set of caverns resembling the Mammoth Cave system. Conway teams up with a TV repair shop owner, a pair of runaway robots, and a boy who’s lost his parents. All have been affected by hard times. As they explore the Zero’s environs, they encounter others whose lives have been similarly upended by personal and professional failure. You play alone, switching between the main characters’ points of view in scripted sequences.

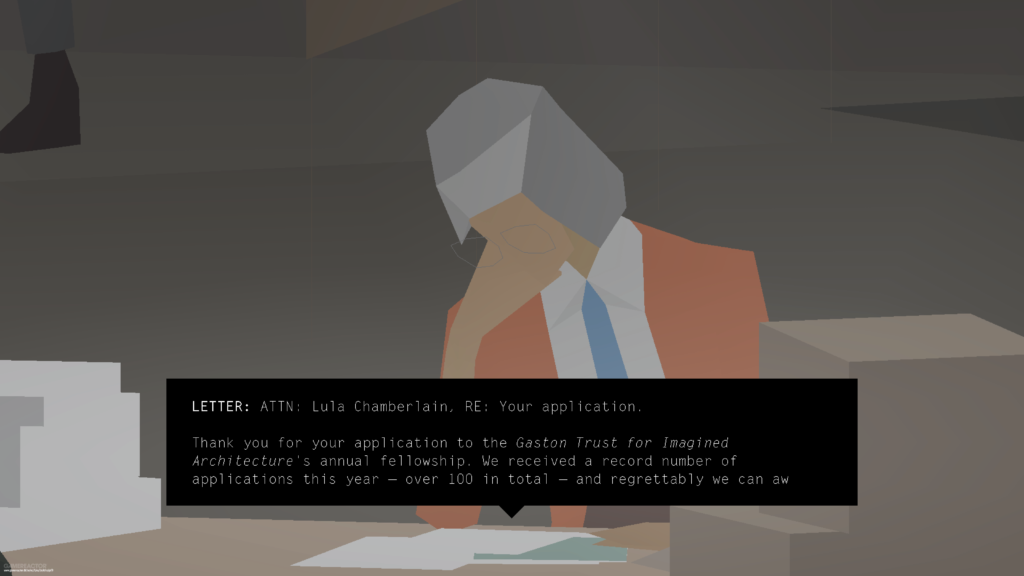

Chamberlain, who is one of the people you meet along the way, has long ago left behind her youthful dreams of being a full-time artist. When you meet, she’s sitting behind a desk at an office job mulling a rejected grant application that would have been a ticket out of drudgery. It becomes clear that her retrospective, which you visit before meeting her, has taken place at some point in the future, too late for her to have profited from it or enjoyed the recognition.

Ghosts in the Machine

Kentucky Route Zero excels at multimedia storytelling. It reimagines Appalachia in sharp angles and gloom, as an expressionist ghost story. Its faceless 3D characters look like they were chipped from unpolished gemstones. Although cartoonish, their appearance fosters sympathetic projection more readily than the never-quite-realistic-enough computer-generated characters of bigger-budget productions. Its monochromatic scenography is lit with splashes of warm tertiary colors. Fonts, maps and other 2D elements emulate the glowing vector graphics of the earliest computer monitors. Its makers have paid fanatical attention to typography, which similarly emulates the appearance of an old computers screen as it unfurls in blocky text bubbles at a slow, speech-like pace. Landscapes and buildings are geometric shapes, not unlike architectural schematics, that serve as a fascinating backdrop against which the action slowly unfurls.

To make the most of its atmosphere, I advise playing Kentucky Route Zero at night with headphones on. Its soundtrack conjures a soft thrum of field recordings of rustling forests, whirring machines, and voices lost in radio static. Babbitt, who composed the audio, uses silence judiciously and music rarely, making the moments when bluegrass and gospel songs emerge from the gloaming even more haunting.

The Zero is populated with ghosts. It’s unclear who’s an apparition and who’s real, including the protagonists. Space and time are similarly out of joint. Along with the recent Financial Crisis, the story incorporates elements drawn from the Great Depression, the 1970s oil crisis, and some point in the future when sentient artificial intelligence exists. Permeable architecture, like the Bureau of Reclaimed Spaces where Chamberlain works, blurs inside and outside. The Zero itself is a loop that you traverse by circling backwards and forwards to get to your destination, as if turning the dial on a combination lock.

A Poetics of Choice

Kentucky Route Zero makes poetry, sometimes literally, out of the choices it presents. In the opening act, the player is asked to guess a character’s computer password, which quickly reveals itself to be an exercise in writing an on-the-fly haiku. The computer presents the player with three short lines to choose from, which leads to three more, then three more. There’s no wrong choice and no going back once you’ve decided. The lines are well-written so that whatever you choose, your poem reads lyrically enough to be a surprisingly satisfying end in itself, and any choice will give you access to the information you need to continue your journey.

There are many similarly poetic moments throughout Kentucky Route Zero. One of the best occurs in Act III, at a musical performance where the player chooses lyrics to a vapor wave song as it’s being performed. Not only are the lyric’s evocation of lost love moving, but they harmonize to bittersweet perfection with the music and imagery. I won’t spoil the details, but it’s one of the most powerful scenes I’ve encountered in a videogame, on par with any work in any other medium I’ve seen.

Some choices have frustrating consequences, particularly when they unnecessarily obfuscate the story. This is especially true in Act IV, which you spend travelling down an underground river. Whether you disembark with certain characters at stops along the way or stay aboard determines how much you learn about them. Given how character-driven Kentucky Route Zero aspires to be, missing significant information prevented me from caring about the cast as much as I could have. Having no control over the permanent departure of one of the lead characters halfway through the story only added to this problem.

“Home is the place…”

Kentucky Route Zero is a worthwhile experience even for those allergic to interactive storytelling. From the small space of the computer screen, it conjures a journey filled, like an actual road trip, with discovery, boredom, and occasional profundity. Given how hard it’s been to travel in physical space, the byways it traverses have been an especially welcome place to spend some time. That there are numerous sights to see as rich as Chamberlain’s exhibition makes Kentucky Route Zero an accomplishment of the first order, videogame or otherwise.

The quiet unpredictability of its story foregoes epic struggle to explore small moments of empathy among a band of losers working to build community in the margins of a Capitalist system that they have otherwise failed to navigate. Conway’s alcoholism gets the better of him after he injures his leg, although his new-found friends work to keep him afloat. A group of renegade computer programmers have formed an enclave in an abandoned mine shaft after having been cast out of academia. People work to restore what remains of a small town already on the verge of collapse in the wake of a devastating flash flood. Our travelers end up here and have to decide if they will stay.

If the game has an overarching theme, it’s the search for home. This is summed up in the final scene, which quotes Robert Frost’s poem “The Death of the Hired Man.” In the poem, a husband and wife who own a farm discuss the return of an old, itinerant farm hand on the verge of dying. The husband cynically agrees to allow the ne’er-do-well to stay, saying, “Home is the place where/when you go there/They have to take you in.” His wife replies, “I should have called it/Something you somehow don’t have to deserve.” A barkeep who has lost ownership of his bar and a barfly who has long been one of his daily companions mull over these lines. They conclude that the wife means that home is a state of grace, owed to us all by dint of our shared humanity, and not something that debt can take away or money can buy.

The Zero is a parable for the many corners of life, online and off, where misfits gather to create a sense of home. It’s not about a heroic fight against the system but about people drifting together to build evanescent communities where they can find common ground, however temporarily. It’s about the potential for creating a sense of “us-ness” and the right of all of us to make compassionate spaces where we can be together outside of concerns engendered by the economy.

How strange to have sat alone with Kentucky Route Zero’s troupe of castaways, using my home office for play by making choices that allowed me to help determine the direction of their lives. It led me to reflect on the various polarities this experience encompassed: alone/together, solo/community, choice/predestination, work/play. I count myself lucky to have been able to circle the Zero and consider these contradictions, all while staying right here in the Valley.

William Kaizen is an art historian and public art advocate. He chairs the Amherst Public Art Commission.