Almanac: Basalt

Basalt cliff at Titan's Piazza. Photo: Stephen Braun

For years I was intrigued by a little arrow on a trail map of the western Holyoke Range pointing vaguely to something labeled “Titans Piazza.” It looked like the Piazza (Italian for an open square or public place) could be accessed from the lovely trail running along the spine of the ridge from the Summit House down to the trailhead on Mountain Road. But on numerous traverses of that trail I never saw anything even remotely resembling a Piazza.

Then last year a friend and I were descending Rattlesnake Knob and came to some confusing trail junctions that were not on my 20-year-old map. Two hikers approached heading up, so we asked for directions. One of them whipped out his map for consultation, and I immediately saw its superiority. As soon as I got home I ordered one from the Appalachian Mountain Club.

Among the many pleasures of the new map was a much more precise location for the mysterious Piazza. It actually lay at the end of a tiny spur trail off Mountain Road about 100 meters north of the aforementioned trailhead. Thinking the Piazza was high on the ridge, I had completely missed, in my numerous drives from the trailhead, the small sign by the side of the road pointing toward my quarry.

It turns out that “Piazza” is a bizarrely inappropriate name. Far from anything resembling a plaza, the “Piazza” is actually a vertical phenomenon—and one of the most interesting geologic features in our region.

The trail to it leads steeply up a talus slope—an enormous pile of rocks at the foot of a cliff (“talus” is also the name for a prominent bone in the human foot). The loose and slippery talus makes for a challenging climb, but after only a short scramble you find yourself standing at the base of a hundred-foot cliff. The lower 20 feet of this cliff is a wall consisting of roughly hexagonal vertical columns of smooth, dark rock. Piled above this palisade and draping over it like some kind of crazy frozen avalanche is an array of bulging, faceted, sharply pointed rock extrusions that look like the multiple rows of teeth in an enormous shark’s jaw. “Piazza” indeed! “Monster’s Maw” is more like it.

In addition to being visually stunning, this formation is a great way to experience the unique geology of the Holyoke and Mt. Tom ranges. These mountains, unlike most others in western Massachusetts, are made of basalt, a dense, smooth-grained rock that is basically solidified lava. The cliff face of the Piazza displays two forms of basalt. The vertical, roughly hexagonal pillars are relatively common, both here and around the world. Devil’s Monument in Wyoming and Giant’s Causeway in Ireland are classic examples. The pillars form when a pool of relatively un-viscous lava cools very slowly. The monster-teeth formations above the pillars are less common and likely formed when a new belch of lava flowed over the older layer and cooled so quickly it preserved the uneven form of a thicker, more clotted kind of lava.

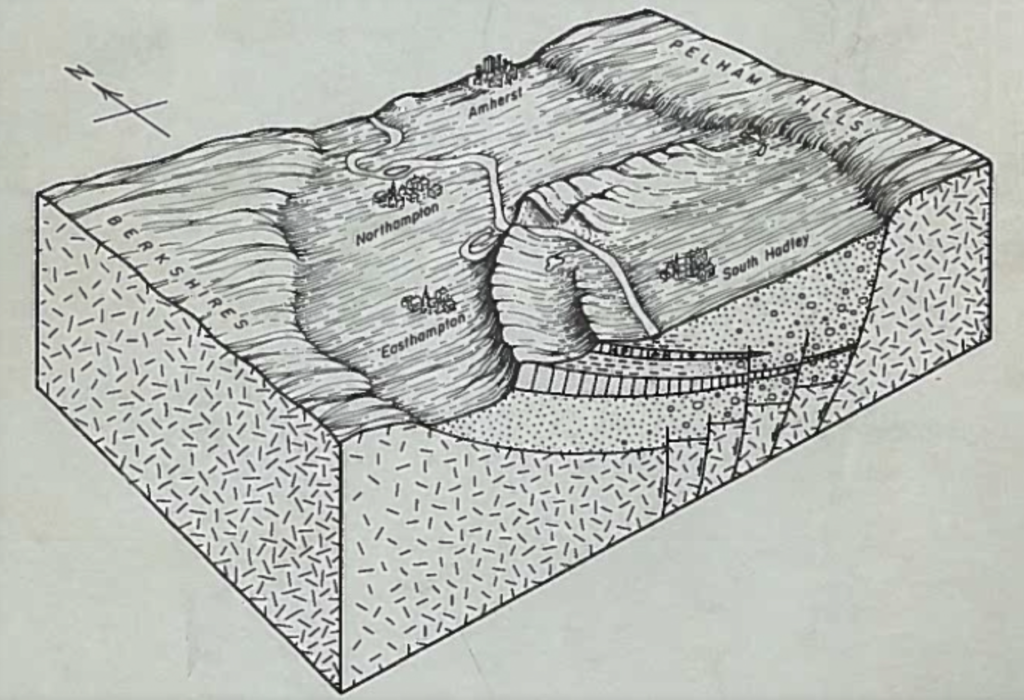

The Holyoke and Mt. Tom ranges are the exposed edge of a roughly thousand-foot-thick layer of basalt formed from lava that oozed from cracks in the earth’s mantle roughly 200 million years ago. This layer has become tilted over time, and is now sandwiched between other layers of sedimentary and metamorphic rocks, from which other local mountains, such as the Sugarloafs in South Deerfield, are made.

Our local basalt happens to be relatively rich in iron, which explains two things you might notice as you pick your way up the talus below the Piazza. First, if you break off a shard of basalt you’ll see that the newly-exposed part is very dark—almost black. After being exposed to the elements, however, the iron in the rock oxidizes to a light brown or reddish-tan. Second, if you knock together two pieces of basalt, especially thin shards, you’ll hear a distinctly metallic, cast-iron-pan-like “clink” rather than a more classically rock-like “clunk.”

Basalt in general is quite hard, and our local basalt is especially so, ranking between 8 and 9 on the 10-point Moh’s scale of hardness. Particularly dense basalt is called “trap rock” and it’s been mined since 1897 from the Lane Quarry off Route 116 at the top of “The Notch.” The Notch used to be much more notch-like because what is now a gaping quarry used to be a 780-foot hill called Round Mountain. Viewed from Amherst, Round Mountain looked like a small peak nestled between 1010-foot Bare Mountain on the west and 1106-foot Mt. Norwottuck to the east. The former mountain has been slowly ground up into crushed stone and gravel used for, among other projects, the runways at Bradley International Airport, the roadbed of the Mass Pike, and the foundations of the UMass athletic fields.

Basalt is the most common igneous rock on Earth, but it’s also been found to be common on the moon, Mercury, Venus, and Mars. Basalt forms anywhere there is—or was—lava, so that means it’s also likely to be found on the 165 rocky, earth-like planets discovered thus far orbiting other stars. If you could take a hike on one of these exoplanets—and maybe some of our distant descendants will do so—you’d probably find cliffs, mountains, and weird toothy formations made of exactly the kind of basalt you’ll encounter on a ramble along the trails of our very own Holyoke and Mt. Tom ranges.

Almanac is a regular Indy column of observations, musings, and occasional harangues related to the woods, waters, mountains, and skies of the Pioneer Valley. Please feel free to comment on posts and add your own experiences or observations.

Best one yet, Steve, taking us from the local to the galactic scale!

And bringing us back to the planetary scale: the revealing hand-drawn graphic reminds me that when hiking the Holyoke Range with friends visiting from Germany and viewing the broad valley below, I’ve pointed out that Amherst could have wound up on southern Europe’s wet coast, claiming that by quirk of fate a couple hundred million years ago, the mid-Atlantic ridge opened a few hundred kilometers to the east, rather than between here and Northampton. (If things hand gone differently, it would have made the bike ride on the Norwottuck Rail Trail more challenging, and maybe that unrealized distance explains the muted rivalry between our two communities? ;-))

In the same vein, there’s more to be said about “Why is the Connecticut River Valley here?” I hope Steve will comment someday on the many-kilometer vertical displacement of the Earth’s crust along Amherst’s western border –the Connecticut Valley Thrust Fault – responsible for name of the street on which he lives :-).

Glad you enjoyed the post Rob, although I’m scratching my head about the connection between the Thrust Fault and Lincoln Ave. Look forward to hearing the explanation some day over coffee!

Terrific post, Steve! Are we Happy Valley humans johnnys-come-lately to great, ponderous dramas enacted without us, over unimaginable spans of time, yet punctuated by the occasional “new belch of lava”? Compare current videos from Iceland of actively belching volcanoes and scary running lava there.

Whoops, my fault: I was not thinking Lincoln, but Sunset: named for its westerly view, made possible by said Thrust Fault