Almanac: Underworld

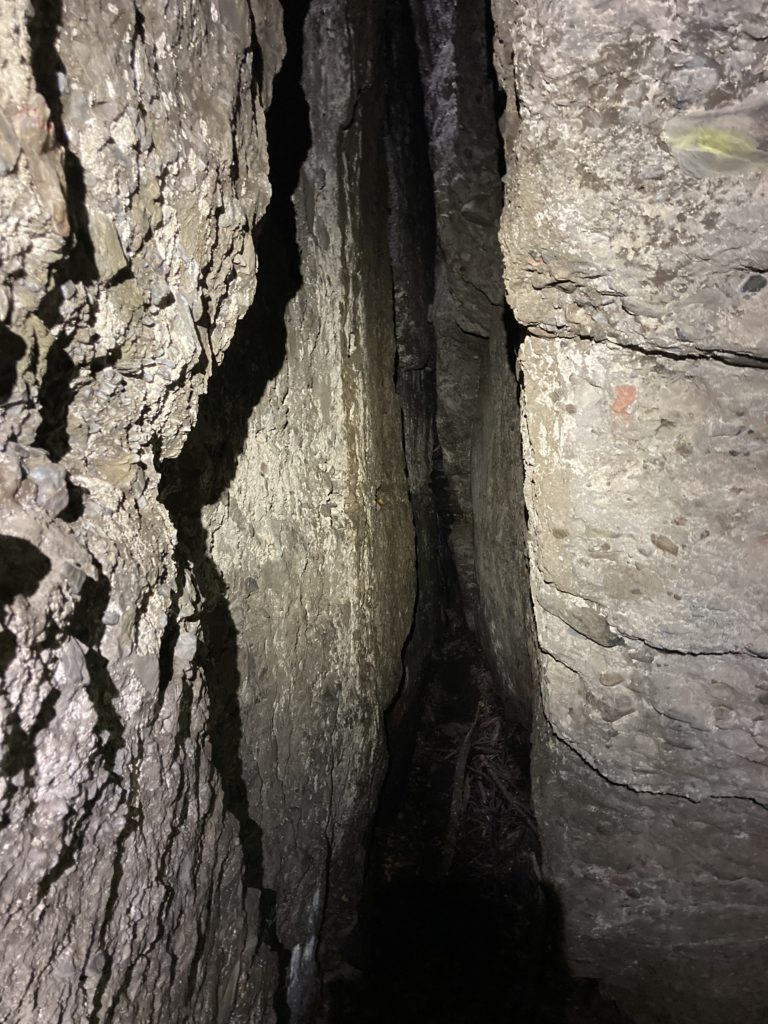

My friend Mark Hart descending toward the narrow east entrance of the Sunderland cave. Photo: Stephen Braun

I’m not particularly claustrophobic, but, still, the hole in front of me was narrow and would require some wriggling to get through. It also wasn’t clear that this hole led anywhere. The idea of wriggling in and getting stuck wasn’t appealing. Hmmm…

My buddy and I had clambered down a rocky crevasse to what we surmised might be the eastern entrance to the Sunderland cave, on the western flank of Mt. Toby. I say “surmised” because there are no signs pointing to the entrance, and only a few oddly-placed signs saying “Caves” along one of the trails running along the side of Mt. Toby. The trails are anything but distinct and we had bushwhacked to the edge of some cliffs that we thought might be where the alleged caves were. We had already passed an impressive cleft in the ground — a straight-sided rock trench about 10 feet wide, 50 feet long, and 30 feet deep. Someone had strung some flimsy string along the edge as a warning, I suppose — but it would have done precious little to save an unwary walker from a likely-fatal fall.

The trench was impressive, but it wasn’t anything like a cave, so we kept poking around until we found ourselves facing the aforementioned hole. It did not look promising.

My experience of “caves” in this area has been less than profound. Horse Caves, for example, on the eastern side of Mt. Norwottuck, are nothing like caves. More like a massive overhang of rock with one very short little hole between boulders through which one can squirm. Likewise, there are “caves” in the big rockfall at the top of Rattlesnake Gutter in Leverett. These can be fun for adventurous kids, but they’re narrow, dank, and are just a dozen feet or so in length.

In fact, most (but not all) of the caves in New England are talus caves — spaces created by the falling together of massive slabs of rock. When people think of a cave, they are usually thinking of solution caves, formed by the slow passage of water through dissolvable rock, such as limestone or marble. These kinds of caves can be massive and full of impressive stalactites, stalagmites, and bizarrely beautiful mineral formations. I once explored, for three days, a solution cave in Tennessee as part of an Outward Bound course and it was an experience I’ll never forget. My expectations for the talus Sunderland caves, in other words, were decidedly low.

After some peering into the hole with our headlamps, my buddy and I decided to go for it. The space was too narrow to pass with our day packs on, so we doffed them and squeezed through, dragging the packs behind. Once beyond the low-ceilinged lemon squeezer, we entered a long narrow chamber roughly 30 feet high with a relatively smooth floor along which we could easily walk. We could see a speck of light far ahead, but without headlamps we wouldn’t have been able to negotiate the passageway.

I’m not sure why I found it so exciting to be deep in a cliff face like this. Maybe because it’s so different from the outside world—no plants, no sun, just rock and water and, probably, some animals like bats that use the cave for shelter. We noticed some relatively innocuous graffiti as we picked our way along, but no litter or other signs of disruption, which was refreshing because so many nifty spots like this get trashed over the years.

We came to a spot where a broad table-like rock blocked the passage. A narrow tunnel twisted upwards and to the left, so we took that. After about 20 feet we joined the main chamber, above the table-like rock. Now we could clearly see the light coming from the western entrance to the cave. We poked around some more, considering, then rejecting, the idea of pushing through some very narrow holes or clefts leading laterally off the main drag. We emerged from the cave into the terrestrial world that now seemed charged with color and life. Even that brief time in the greyscale underworld sharpened my appreciation for the hues of autumn and the rich smells of the forest.

We kept exploring along the base of the cliffs and found several other cool-looking crevasses, overhangs, and a massive slab of rock tilted against the cliff face forming a kind of arch under which you can pass. The geology of the cliff is interesting: a lower layer of slate, created from layer upon layer of ancient lake sediment, topped with a roughly 50-foot-thick layer of conglomerate, which is a common form of metamorphic rock in this area composed of rubble that has been fused by pressure into a lumpy, variegated rock.

The town of Sunderland claims that the main Sunderland cave, at about 100 feet, is the longest in the state. That’s a little like Florida boasting that its Britton Hill, at 345 feet, is the tallest mountain in the state. Still, this tops my list of local cool places to visit — and that’s saying something because we’ve got a lot of cool places around here.

You can find photos and some general directions to the caves online. If you want to explore, you’ll need a light (using your phone’s light would probably be possible, but a brighter light is both safer and better, and reveals the dimensions of the cave). Also consider wearing a helmet of some kind — a bicycle helmet would do. I will definitely be doing that next time I visit, which will be relatively soon because I haven’t gotten my fill of that subterranean space.

Almanac is a regular Indy column of observations, musings, and occasional harangues related to the woods, waters, mountains, and skies of the Pioneer Valley. Please feel free to comment on posts and add your own experiences or observations.

It’s always a thrill to learn from Steve what I never knew was in my very backyard. Thank you, Steve, for taking me exploring with you!

While I read all of the news and commentary in the Indy with gratitude, I read Steve’s Almanac with a special pleasure. I do not naturally inhabit the world he reveals, but if I had read his beautiful essays fifty years ago I might well have been persuaded to explore it and appreciate it as profoundly as he does. But this piece on caves has a special resonance with me, since it connects with – and belongs to – the vast literature on caves and the mysteries and monsters as well as the beauties within them. The symbolism of spelunking is not hard to fathom and even Steve’s exploration of our modest local caves adds to it.