Becoming Human: Moving At The Speed Of Trust. Greenfield’s Stone Soup Café

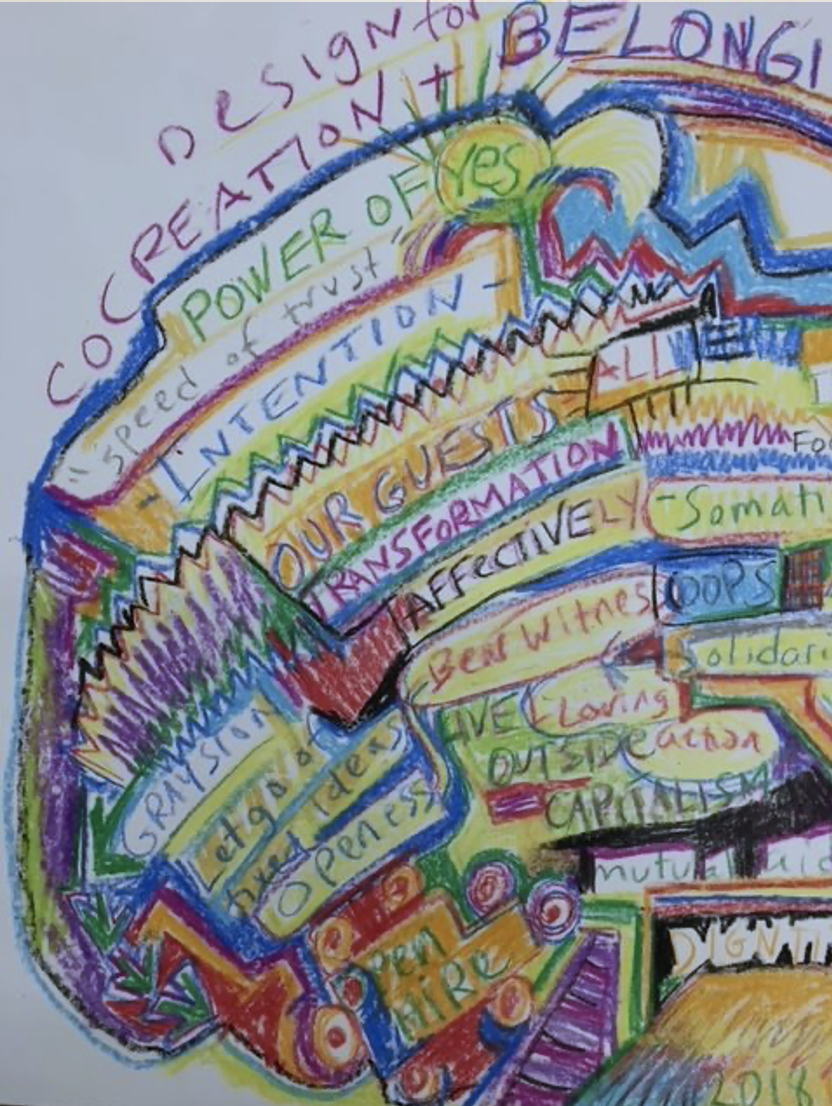

Note taking sketch drawn by Whitney Robbins during the April Conversation at Stone Soup, Greenfield.

Editor’s note: Becoming Human returns this week after a brief hiatus. Each edition of Becoming Human features an article, reflection, interview, poetry, or other types of expression that engage with a creative community or municipal effort. These will include original features that discuss a local initiative and also stories about efforts in other parts of the world that we might learn from. The growing narratives, relations, and power from which other worlds are being assembled, maybe, can help reorient our hope and desire—and resignation—away from the death drive of white supremacist, heteronormative, capitalist modernity, and towards an open, uncharted horizon of radical egalitarianism and towards the reality that other worlds are in the making or already here. For the full introduction to Becoming Huaman that appeared in its inaugural column, look here. For previous Becoming Huamn columns, look here.

In April, Anthropology 341 Building Solidarity Economies visited Stone Soup in Greenfield, MA. Anthro 341 is a course in the department of Anthropology at the University of Massachusetts and part of The Building Solidarity Economies Project–an assemblage of classes and projects endeavoring to explore and help advance conditions from which communities are able to imagine and act outside of the dictates of capitalist modernity.

After hanging out with Stone Soup community members along an artfully decorated sidewalk, looking over food and grocery items in the free store, and eating a delicious meal including ginger carrot bisque, curried lentils, and quinoa, Stone Soup members and leaders Whitney Robbins, Jansyn Thaw, Kirsten Levitt, and Brandon Shantie talked with us about their work. The following essay builds from this encounter.

“We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.” –Arundhati Roy, 2020, The Pandemic is a Portal

Stone Soup Café, a pay-what-you-can restaurant in Greenfield, has recently garnered a lot of high-profile attention. In late March, Stone Soup met with US Congressman Jim McGovern and in early April State Senator Jo Comerford dropped by the café to help with the weekly meal. These visits bookended an official announcement of a sizable grant from the state supporting a pilot program for a culinary institute at the café, a long-term vision of Stone Soup’s executive director and chef, Kirsten Levitt.

Underlying these exciting headlines and happenings is a fundamentally more important story of deep, shared reflection and transformation that the Stone Soup community has engaged in over the past few years. Stone Soup is embodying ways of being, knowing, and doing that they want to see in the world. And they are gaining clarity around what they are rejecting and refusing.

Says Board President Whitney Robbins, “Capitalism is what we are up against…we haven’t thought about ourselves as part of a solidarity economy until recently, though [we were already acting in that way].

A ready attribution of hardship to capitalism has become increasingly commonsensical for many; inequalities have reached record levels and the historical roots and structures of violence have become more publicly discussed. And it was the pandemic, along with the Floyd Rebellion, that set the stage for Stone Soup to move through a portal—”a gateway from one world to the next” as Arundhati Roy has discussed, and brought the café and community into a more intentional process and politics of becoming.

Away From Alienation and Violence

From its very beginnings Stone Soup was intended as a response to alienation and social violence. Emerging from the teaching and practices of Zen Buddhism, a weekly community meal was started in Montague in 2010. A short time later, this meal became formalized (and more accommodating to food insecure community members) and moved into All Souls Church in Greenfield in 2011, where the Zen Peacemaker tenets and agreements continue to influence efforts.

Executive Director and Chef Kirsten Levitt explains how the three tenets relate together, guiding an embodied praxis for the community “what the first is, is opening yourself up, letting go of all your fixed ideas; to really be able to then bear witness, to the joy and suffering that’s happening in the world, so that then you can, third tenet, move into loving action.”

Prior to the pandemic, the café meal was created, served, and eaten in/as loving action; it animated an inviting, participatory, collaborative space. Stone Soup works with local farms and non-profits to gather healthy, whole ingredients. Menus are created each week from seasonal and available ingredients with food preferences and restrictions in mind—most items are gluten free and many are vegan. Community volunteers make, serve, and clean-up together. Many volunteers are regular members of the community, or are food insecure themselves (or have been in the past). Volunteers eat the meal along with everyone else.

The provisional commons created each week worked to flatten hierarchy between differently positioned community members; it created a space where the three tenets could be more readily practiced. Other practices like live music, a community circle preceding the meal, and “council”—where community members share and listen to each other in a more intentional fashion—helped to actualize the Stone Soup’s mission “to create a community space where people from all walks of life come together to share nourishment, connection, and learning for body, mind, and spirit.” Efforts towards this mission could be seen and felt by anyone attending the meals, and is described in numerous testimonials by stone soup community members, including staff and board, who help constitute and experience Stone Soup as loving action.

Says Levitt, ”It didn’t matter if I had had the worst week at school. When I walked in the door to do prep on Friday, I might have been quiet for an hour, but then all of my friends who were there–we were all working together–I would feel connected and loved. I could just become better, and I could let everything that happened all week-long go, because we were doing this next thing and it was fun.”

Volunteer Coordinator Jansyn Thaw similarly describes Stone Soup as a community of care and connection, “I can bring my full self whether it’s having a panic attack and like crying and not being able to go to a meeting, and everyone’s okay with that. Or if it’s me on my best day and I’m being a boss. I can show up however I am, and It’s accepted. That feels really cool.”

Stone Soup’s pay-what-you-can economic model is itself oriented towards inclusion and care. Pay-what-you can restaurants and stores work on non-market logics. Rather than embodying the self-interested, rational actor that is said to animate economies, pay-what-you-can is more closely aligned with the principle—“from each according to their abilities, to each according to their needs.” People pay what they are able for themselves—even if that is at the time, $0. Or, if they are able, people might consider possibly contributing to/for others beyond the cost of their own meal.

The promise of pay-what-you-can for Stone Soup is that it might operate concurrently on two levels—1) provide healthy, dignified meals to the many food insecure folks in the region and 2) create a non-heirarchical space where community members come together to build relationships across and through difference. Pay-what-you can enterprises can be set up in different ways and have had varying outcomes. And, some criticize their perceived limitations and scale. For Stone Soup, fully actualizing the model has been an ongoing process.

The Pandemic As Portal

The pandemic made a community meal impossible. It also created more of a demand for Stone Soup which quickly expanded from producing meals for 200 to doubling that amount. This required change at many levels. Explains Levitt, “at the very beginning of COVID, there were 25 of us on Zoom saying, ‘hell no, we won’t shut down. We need a delivery program. We didn’t have a delivery program. Do you know how to do a delivery program? No. Who cares? We will [figure it out] together.”

No longer eating together in a shared space, Stone Soup had to rethink how to actualize their mission. Long-time community and board member Whitney Robbins, who had just become board president, explains the challenge, “we can’t come together anymore, we can’t do our council practice, and I don’t [yet] know how to be a board president, but I love our mission, and I love our three tenets and four agreements, and [I think] if we live by those, we will transform ourselves.”

And they have done, and are doing, precisely this. Stone Soup expanded the board, created a more participatory, inclusive space in board meetings themselves, and created more and more channels for community involvement, reflection and transformation. They reconfigured what remaining communal space was available–primarily the sidewalks and parking lot outside the building–filling it with paintings, renderings of stone soup principles and values, and the like. “We used to do the learning and connecting by breaking bread together,” says Robbins, “ so we decided we needed to create that community [in other places] on the sidewalk through art and murals.”

Stone Soup also brought the community closer through collective education. Robbins again, “[we asked each other] what are we doing with our learning, and we decided, let’s learn about mutual aid. We think we are more mutual aid than charity, so we started an on-line reading group with Dean Spade’s mutual aid book.” This mutual aid reading group, as well as subsequent anti-racist reading groups and learnings, then helped to inform practice. Stone Soup started a solidarity committee to build transformation within Stone Soup and connect with movement work. The solidarity committee has facilitated the creation of a statement on anti-racism with corresponding practices, an in process land-acknowledgement, and a gender inclusivity statement. The committee is one place where stone soup members can bring ideas and help get them launched. For example, seeing a need to create space for and build community through Spanish speaking community members, Ester Gonzales Martin, organized (and facilitates) a Spanish hour at the café.

Further responding to community needs and desires, a Free Store soon joined the weekly meal. And efforts to include more voices and spread-out decision-making continued. For example, a community survey was launched involving community members themselves participating as researchers throughout the process.

These collaborative, inclusive approaches towards transformation require an orientation that is thoughtful, considered, and open to possibility. Explains Thaw, “all of this [the community survey and collaborative practices more broadly] takes a lot more time than just, for example, “doing a survey”, so we try to move at the speed of trust.

Emergent Possibilities

Moving at the speed of trust, at the speed of relationships, takes time and logics that don’t correspond with urgencies of our dominant systems. So, there are tensions for Stone Soup to navigate as it deepens and expands its community, and more and more opportunities emerge. For example, how does Stone Soup navigate what some have described as the non-profit industrial complex as it seeks to support all of its efforts? Funding cycles, reliance on donors, the constraints and parameters of grants, can steer and shape practices that might be at odds with Stone Soup’s desired approach.

On another level, Stone Soup must contend with the conditions of capitalist modernity that it seeks to reject. For example, perhaps Stone Soup will parlay the culinary institute into a social enterprise, like their progenitors? Or maybe they will work with the growing network of worker cooperatives in the state, and in Greenfield, to help culinary institute graduates build workplace autonomy and democracy amidst a Great Resignation in the exploitative service industry? Or, perhaps more likely, Stone Soup community members will marshal their collective wisdom and creativity for an as yet unknown, relational project oriented towards care.

Stone Soup is not an organization led by business “experts” or professional organizers. It’s much more remarkable. It’s led by a growing community of brilliant, caring people, bringing their whole-selves to the work, and moving at the speed of trust.

Acknowledgements: This column—and the articles cited within—are in dialogue and solidarity with numerous collaborators and comrades including Vin Lyon-Callo, Meredith Degyansky, Penn Loh, Stephen Healy, students in Anthropology 340 – Other Economies are Possible, Anthropology 341 Building Solidarity Economies, Anthropology 597CC Community, Commons, Communism, and the pluriverse of world-making and world-defending efforts, movements, and projects in Massachusetts and around the worlds.