The Jones Library, The Old Whipple House Window, And Our Central Fire Station

The Whipple House window in its present location, the Special Collections on the third floor at the Jones Library. Photo: Hetty Startup

Amherst History Month-by-Month

With the concerns and recent press for the Jones Library demolition and addition, I have been hesitant to post this story from the past but – in the midst of the Library vote last year, the architects’ schematic drawings, the budget and current uncertainties, I thought it might be interesting to ask this question: will the Whipple House window survive as part of the new addition?

I had never heard of the old Whipple homestead in Amherst center when I moved here. It came up as a topic in a meeting on Zoom in public comment this past spring when the Historical Commission considered protections for the many historic houses in our downtown. The area under review was from the ‘top’ of North Pleasant at Amity Street (that used to be the old road to Hadley) on up northwards to the new rotary by Kendrick Park.

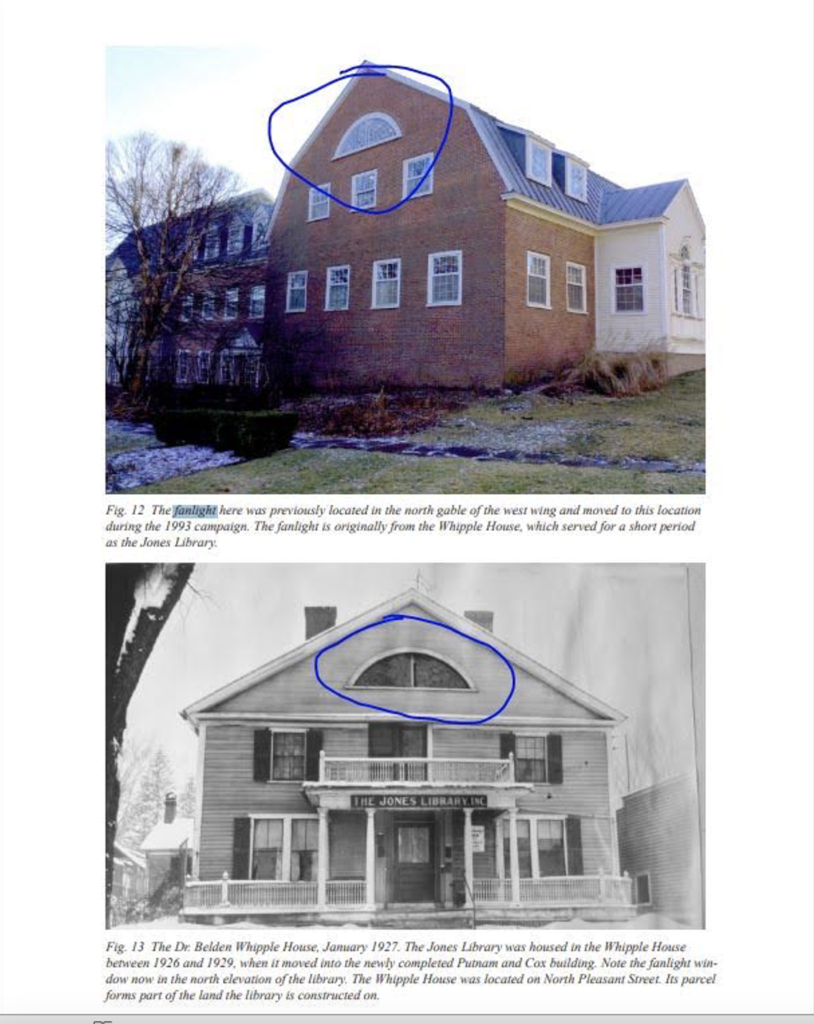

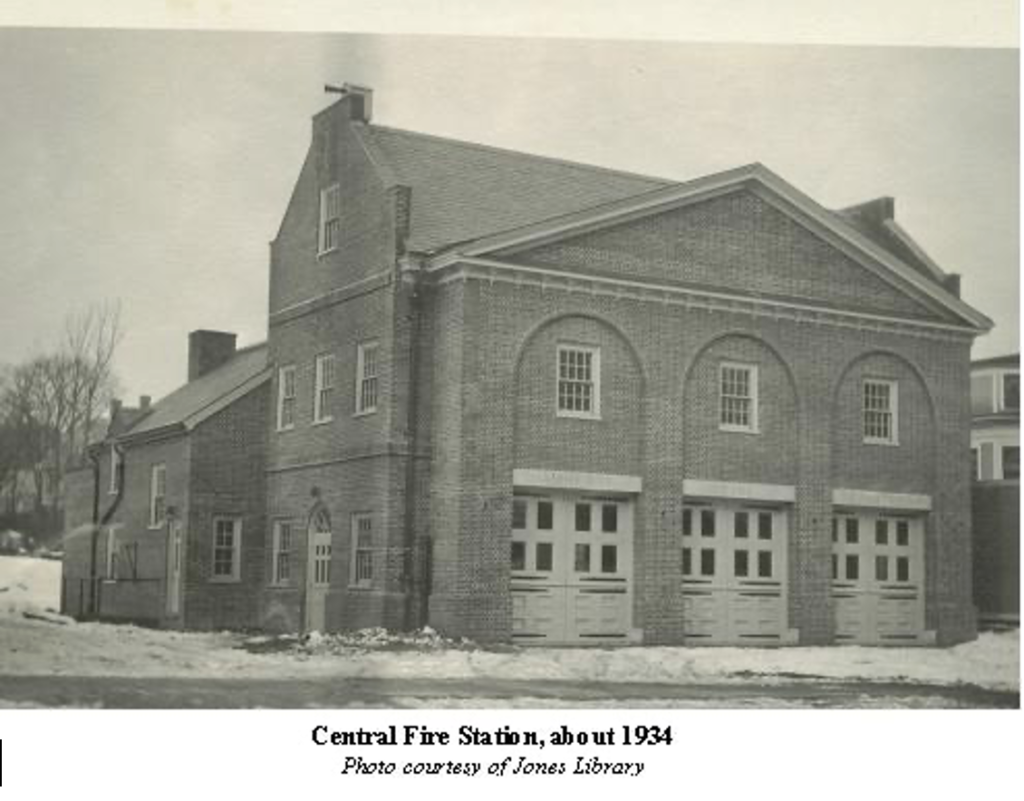

The Whipple House does not survive, except in photographs and it was razed to make way for the town’s new Central Fire Station (1929-30) as the old fire station was no longer adequate. We are faced with the same issues again. But that is another story for another time. But before the old house was pulled down, a beautiful leaded, elliptical-shaped window (a little bit like a fanlight over a front door but much grander in scale) was saved. It was clearly beloved and incorporated into the Jones Library many decades later when the 1993 addition was completed.

This distinctive window from the Whipple House isn’t very visible in historic photos. In an example below, you can just make out the shadow of the unusually shaped window on the third floor in the triangle shaped gable roof. You can also see the then new library on the left in the background. The photo was taken by Lincoln Barnes (1879-1966), the official photographer for Amherst College, who also had a studio on Main Street from 1920 to about 1955.

The Jones Library story is itself interesting. It was incorporated in 1919, after the First World War following a bequest from Samuel Minot Jones (1836-1912). It opened to the public on South Pleasant and Amity, on the second floor of the Amherst House, a hotel which burned down in a winter fire in 1926. The site is where the Bank of America now sits.

Two days after the fire, while plans began to take shape across Amity Street for the new library, its operations, staff and collections were moved into the Whipple House across the road, on North Pleasant. From then until November 1, 1928, when the Jones opened, the staff made the Whipple House its temporary quarters. It is a little like what is happening now with the North Amherst library. As they break ground for the handsome new addition, its staff and collections are being welcomed in the nearby Mill District at 81 Cowls Road.

Once the 1928 Jones building on Amity was finished, with everything fit-to-purpose including an elegant interior, the books and staff moved in too. One more link to the past is that the 1928 Jones building had as a cornerstone, a remarkable nine-hundred-pound slab salvaged from the Amherst House that had been laid on October 19, 1927.

When Special Collections was given dedicated space in the 1990s addition that mostly overlooks the garden and the Amherst History Museum, the distinctive Whipple house window reappeared, given pride of place in a reception and exhibition area located next to the Special Collections Reading Room. You can see it today by following the signs, taking the stairs or the elevator to the third floor.

In significant ways – and for another article perhaps – the Jones was designed by the architectural firm Putnam and Cox, with credit to its partner, Allen H. Cox. He intentionally designed it to recall traditional Connecticut Valley colonial-era residences from the 1700s and in this way, the Jones Library was not a more typical, classical ‘temple’ based on ancient Greek and Roman ideas. Incorporating the window from the Whipple House much later is a small but significant reference to these earlier design decisions.

Sharing the story of this window – and its context – is a bit like a tale of an adopted offspring of the ‘person’ that was the entire Whipple home. Or perhaps it’s a rich sub plot in a novel. In any case, I admit it is very fanciful to think about a building as a person but it serves my purpose in an argument that maybe our buildings are our town’s family photograph album made visible over time.

When the Whipple House was demolished to make room for construction of the town’s new Central fire station, the builders made reference to the old homestead. With its gable (triangular-shaped) front, the fire station imitated the design of the Whipple House.

Many of us, I hope, have photos stashed away that tell of the time and the people we come from; photos that help shape our identities, assist us in belonging and remembering. This is not true for all peoples, and in grievous situations, some of our peoples have been hidden from history. So, gentle readers, to be able to pore over a family photo album – or look at a historic building like the Jones Library – can be a gift, because we can clarify our histories. These days, DNA tests can help us to re-establish some of the stories and people whose images and even names have been suppressed and literally ‘hidden from history.’ In a similar forensic manner, the disciplines of public and architectural history as well as community archaeology can sometimes help to establish what was literally demolished and built over when a building of historical or architectural significance does not survive.

Change happens all the time and it can achieve good, mixed or disappointing results. The historic character of a town’s buildings – when they were built; what materials were used; what they replaced; who they were built for; who they were built by; perhaps when, how and why they became ‘lost’ from the material record but survive in memory, photographs or maps – is sometimes a complex story. Perhaps like that ancestor who moved away, or the relative who you see only at Thanksgiving, a building can be like the mystery person in the story but pivotal to a family or person’s claim to their past, present and future. I think this also holds true for our buildings, a tangible and invaluable record, showing us where we came from, and what we are made of. What we can still sustain and build from now and into the future.

Amherst History Month-by Month is a monthly column on historic preservation, taking a look at Amherst’s historic buildings and neighborhoods and the stories behind them. It may also, from time to time, explore the challenges of historic preservation in a town such as ours that is so rich in historic resources. Hetty’s next article will be about Hazel Avenue and the A.M.E. and Hope Churches. See previous columns here.

Hetty Startup lives and works in Amherst and is a member of the Amherst Historical Commission. The views expressed here are her own and do not reflect the determinations of the Commission.

This is a deeply important commentary, both in its specifics and in its general attitude. That it is beautifully and elegantly written enhances its value. I hope that the Planning Board and the Town Planning Department will take it seriously.

The town has several areas designated as Historic Districts, and Hetty Startup raises the question in my mind – what is not a historic district? Using the “family photo” analogy, what buildings in Amherst are not part of Amherst’s history? This does not mean that all buildings should be prized or saved; downtown now contains huge buildings that I dislike but which are now part of Amherst’s history. Downtown still contains buildings that are undistinguished – just like families.

And this attitude, of course, must be extended to our unbuilt spaces, perhaps especially now when the Master Plan is under review. Whenever I drive past the Henry Hills houses on Main Street I grieve the loss of the grand lawn, now broken up by houses and shrubbery. I am apprehensive about the fate of the lawns and gardens between the Jones Library and the Strong House as the Jones expansion is endlessly debated.

In whose hands do these planning and development decisions rest? The 2010 Master Plan was approved by the Planning Board and never presented to Town Meeting for either approval or endorsement. No doubt this was to avoid a controversial debate about a state-mandated and largely unread document. If we take the Master Plan seriously, as I hope we will this time, how do we decide what of our past to preserve and integrate into our landscape and streetscape? Can we construct our future and preserve our past at the same time?

I am gratified to know that Hetty Startup will embrace the whole town as she proceeds with her series on historic preservation.

Just a note about the 2010 approval of the Master Plan. The final draft was the result of lengthy, careful, and sustained rewriting by the Master Plan Subcommittee, of which I was a member. I was the lone no vote on both the draft that was present to the full Planning Board, as well as on the final approval of the plan itself. I voted no both times due to the addition by the former Planning Director of a seemingly innocuous phrase: that of directing development to “specific districts and neighborhoods.” By shifting the original focus from the town center and village centers to other as-yet-unnamed areas of town, I believed that this gave the powers that be — whoever they might be — the ability to target almost anywhere in the town for development, and the excuse to claim that “the Master Plan says that this is what residents want.” My fears were further bolstered by a land-use map, also presented by the former Planning Director, which drew large circles radiating out from both the town and village centers, encompassing significant portions of the town, and claiming that these were appropriate areas for increased density and development.

The Master Plan’s language is broad and general. In the 12 years since the plan was adopted, the Implementation Matrix has never had a single detail filled in (https://www.amherstma.gov/DocumentCenter/View/3138/Appendix-A—Implementation-Matrix?bidId=), thus failing to translate the broad possibilities of theory into the limits of reality. This allows the most insistent voices to promulgate their interpretation of how the Master Plan should be implemented, and opens the possibility for them to claim to alarmed residents that the development rising around them is of course exactly what they wanted.

That’s a beautiful window. I’m so happy to know the history of it.

Late to the table, but very interested in the goings-on. Denise Barberet – was that Planning Director Jonathan Tucker?

I well remember that Denise was a voice in the wilderness.

JP: I believe you’re batting 1 for 1 tonight!

Yes, Jim, that was former Planning Director Jonathan Tucker.