Opinion: Why Is The Town Of Amherst Still Called Amherst?

Jeffry Amherst. Photo: Wikipedia

In 1757, John Nash, Isaac Ward, and Nehimieh Dickinson, three of the leading citizens of “East Hadley”, petitioned Governor Thomas Pownall Esquire, Commander-in-Chief of His Majesty’s Provinces in Massachusetts, to create a new precinct, independent of Hadley, which they recommended be named Amherst. In their letter, the petitioners extolled the virtues of Major General Jeffrey Amherst, who was being hailed as a hero in England’s war with France and had not yet been associated with the heinous recommendation to use germ warfare against the indigenous peoples of New England.

On February 13, 1759, Governor Pownall signed the documents establishing the new precinct of Amherst. According to UMass Emeritus Professor Peter d’Errico, the author, Frank Prentice Rand wrote, in The Village of Amherst: A Landmark of Light (1958), wrote that “…at the time of the naming, Amherst was the most glamorous military hero in the New World.”

It is unlikely that Nash, Ward, or Dickinson would have known of Jeffrey Amherst’s active support of the plan to use smallpox-inoculated blankets to infect the native population. It was not until four years after the naming of the new precinct, that Major General Amherst included the following postscript in a July 13, 1763 letter to Swiss mercenary Henry Bouquet: “This is a good idea to spread smallpox – just be careful you don’t get it yourself.” Given a few days to think about his recommendation, Amherst wrote Bouquet again on July 16, saying… “You will do well to try to inoculate the Indians by means of blankets, as well as to try every other method that can serve to extirpate this execrable race.”

Note: according to Google, possible synonyms for “execrable” are: abhorrent · abominable · accursed · atrocious · confounded · cursed · damnable · defective …

Professor d’Errico suggests these letters to the Swiss mercenary were not anomalies but part of a pattern, as he references the following quotes from Major General Amherst’s correspondence during the summer of 1763…

- “…Measures to be taken as would Bring about the Total Extirpation of those Indian Nations” (July 9)

- “…their Total Extirpation is scarce sufficient Attonement….” (August 7)

- “…put a most Effectual Stop to their very Being” (August 27). 1

It is interesting that we may, on occasion, hear today the suggestion that Lord Amherst is somehow not culpable because the recommended act of germ warfare may not have occurred, or if it did occur, it was probably not effective. The written documentation remains clear that Amherst supported an act that would be recognized as genocide today. Even so, diseased blankets were just the “tip of the iceberg” of a 500-year pattern of genocide that took many other forms in the former British colonies and later in the United States.

In retrospect, we can understand why Nash, Ward and Dickinson might support naming their new precinct after the illustrious war hero. It is more difficult to understand why the citizens of the many towns and organizations in Canada and New England that currently carry the name of Lord Amherst, would continue to honor his memory in the same way.

Most attempts to change the name Amherst, have been sidestepped by local governments. In 2019, the City of Ottawa decided not to change the name of a suburban street called Amherst Crescent “because no one officially requested it, and… there’s no proof that it was named after an 18th century British general who advocated for the genocide of Indigenous people.” In 2017, the Premier of Nova Scotia refused to change the name because “he has not heard concerns about the town of Amherst being named for the controversial historical figure.”

On the other hand, Montreal Mayor Denis Coderre, while explaining why a street named after Lord Amherst was changed to Atateken Street, declared that “he [Amherst] wanted to exterminate Indigenous peoples.” Coderre didn’t wait for a formal complaint from an aggrieved party when he said “Goodbye, Mr. Amherst,” the same day that he announced the addition of an Iroquois symbol to the city’s flag. Michael Rice, an Indigenous studies specialist with Sir Wilfrid Laurier School Board, called it “one of the best decisions that Coderre has made, because [Amherst] was universally hated by native people at the time.”

When a request to change the name of Port-la-Joye–Fort Amherst National Historic Site on Prince Edwards Island was being debated, elders of the Mi’kmaq Confederacy argued that Lord Amherst was an enemy of Indigenous peoples. Parks Canada, which managed the fort and had ignored a request for the name change in 2008, issued a statement in 2018 “in the spirit of reconciliation” saying the Mi’kmaq name “skmaqn” (pronounced Ska-MAA-kin) will be added to the park’s name.

Of course, the name “Amherst” has different meanings for people living today than it did in 1759, when it was a way to celebrate the war victories of the British military. And frankly, changing the name of the town might seem like a “heavy lift” for a local government. But perhaps public and private organizations carrying the name Amherst would consider a name change, as a way of bringing attention to the history of indigenous genocide by the colonial settlers.

Reporting on Amherst College’s change in the name of their mascot, Peter d’Errico wrote in Indian Country Today, “Lord Jeff can take on a new role, as an example of the way that America—or any nation—can revisit its history: not to deny it or cover it with whitewash (which amounts to the same thing), but to face it.”

Perhaps organizations that continue to “raise up” Lord Amherst on their building signs and letterhead would consider a name change as a way to shine a light on the past, so that we do not forget. Professor d’Errico continues… “Every generation has a duty—to study this lesson and to find ways to leave their own history enlightened by acknowledgment of their own mistakes and misdeeds.” A name change might be a beginning of a longer process of reflection, reconciliation, and reparation, for as d’Errico concludes “without learning and critique, removing a symbol of history becomes only a way of hiding the truth.”

In a recent Amherst Indy article on local native sites, Hetty Startup boldly stated that the “Indian ‘wars’ are still being waged in other guises.”. People and the land continue to be exploited by accepted practices of the dominant business culture. Perhaps by acknowledging the “original sin” of the European colonialists, we will begin to find the courage to see that systemic oppression continues today.

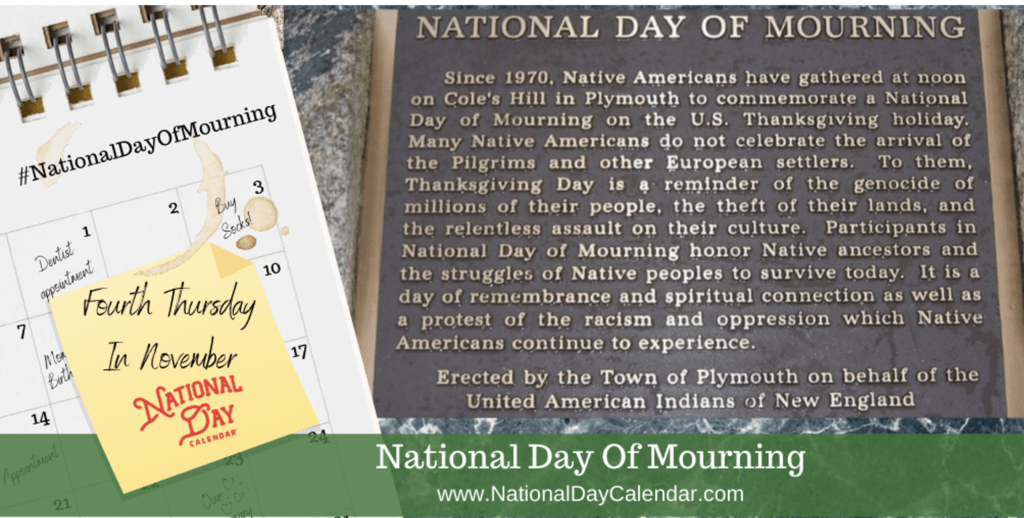

At the very least, we might support Native American reparations, ranging from a voluntary tax on stolen lands, to having the true story of colonization by Europeans being told, something that seems particularly important as we again approach November 24, 2022, the National Day of Mourning. And perhaps if we are truly courageous, we might ask ourselves why Amherst is still called Amherst, today.

John M. Gerber is a long-time resident of Amherst and Professor of Sustainable Food and Farming in the UMass Stockbridge School of Agriculture. His blog page can be found here: https://changingthestory.net/

I’m only half kidding in suggesting we explore reuniting with Hadley, so not only might we collaborate on such things as a new public works building (they are also hoping to build one), but benefit from the commercial tax base along route 9 (Amherst must be a huge percentage of their business), and also rename Amherst as East Hadley. The only evil Hadley I found on Google is a secondary villain in the Shawshank Redemption.

You might be onto something, Ira. If Amherst were to inherit Hadley’s tax rate, the annual tax bill for the average Amherst single family home would fall by $3679.

By the way, thanks for a very thought-provoking article, John Gerber.

it’s an abomination that any city, town, county, or street etc. be named after this man. ni

it’s a tangible blight on this otherwise wonderful community. it has real meaning that his name has not yet been removed. it WILL happen someday. the question is: how much longer do you want to live with this terrible poison….and the reality that nothing has been done about it

meanwhile there are so many lovely alternatives that could bring pride, beauty, a smile….emily, amethyst, nipmuk, peace, love, joy, solartopia, julius irving….take your pick. which among them is not better than what now poisons the mind and spirit?

Harvey Sluggo Wasserman

There have been at least three efforts in recent years to change the name of the Town of Amherst to something with a more humane sensibility than Amherst. (We apparently officially became known as the City known as the Town of Amherst when we changed to a Town Council form of government but that doesn’t work to remove the genocidal association).

Vince O Connor appealed to the town council in 2022 to change the name by referendum, with suggestions not limited to Tubman (for abolitionist Harriet Tubman) Sumner (for anti-slavery Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner or Emily (after bellowed local poet Emily Dickinson).

Brendan McWade launched a petition on Change.org in 1995 arguing that the name Amherst should be abandoned because of the dishonor associated with the legacy of Jeffrey Amherst. The petition garnered almost 1400 signatures and drew its inspiration from a student petition organized in 1992 to protest the Columbus Quincentennary. He suggested Norwottock and Dickinson as alternatives.

In 2017 Belchertown resident William Bowen circulated a petition requesting that the town change its name.

In the first edition of the book Lies My Teacher Told Me (1996), James Lowen refers to efforts to change the name of our town. He might have been referring to McWade’s effort but perhaps another. My copy has disappeared and the reference is missing from the second edition.

None of these efforts gained much traction but their persistence suggests a unsatisfied need to further explore the issue.

We know that there have been successful efforts elsewhere to remove the names of villains from public places and to remove racist mascots from college campuses. Thanks to John Gerber for this reflection,for reminding us that our failure to confront history is consequential, and for sharing Peter d’Errico’s words: “every generation has a duty—to study this lesson and to find ways to leave their own history enlightened by acknowledgment of their own mistakes and misdeeds.” Gerber concludes “A name change might be a beginning of a longer process of reflection, reconciliation, and reparation, for as d’Errico concludes “without learning and critique, removing a symbol of history becomes only a way of hiding the truth.””

Amherst, MA would do well by fostering a new public discussion on how we would like to be known and why.

“Norwottuck” is a close approximation to what this area was called by its residents 400 years ago. And much of the land now occupied by UMassAmherst (nee Massachusetts Agricultural College) was also used for agriculture for the past 3000 years. So wouldn’t it be a mitzvah to again rename our campus

University of Massachusetts Norwottuck

and see what happens next?

Why not a name that indigenous people used? How, in our enlightened and progressive community, can we continue to label ourselves after the despicable Lord Jeff? Can you imagine many in our town being okay with a statue to Robert E. Lee on the “North Common”?

Let’s ask for the opinion of those of the Nipmuk community (they are actively among us) or, perhaps, settle on something handily applicable to many palatable interpretations.

“Trinity” (there is no other in Massachusetts), works for me. Today it could represent the coming together of agriculture, education and the people. Long ago it could have spoken to the flowing water, the mountains, and the valley, or the fresh fish, the wild game and the fields for growing.

There need not be any nod to a person, political or otherwise. (Dickinson was the name of her father, Tubman the name of her first husband-not a great guy- whom she left to seek her freedom).

Other communities and organizations with tradition have made changes. Are we not enlightened and progressive enough to do the same?