Indy Editors’ Picks: Recommended Good Reads from 2023

Photo: Booshop.org (CC BY-SA 2010)

Compiled by Art Keene and Jeff Lee

This is the fourth year that we offer recommendations from our editors and staff writers of some of our favorite reading from the past year. Feel free to share your own best reading experiences from the past year in the comments section below. And after our own recommendations, we offer a compilation of links to other “best of” lists for good reads from 2023.

If you’d be interested in writing book reviews for the Indy, please drop us a note at amherstindy@gmail.com.

Here you can check out our favorites from 2022, 2021 and 2020.

Kitty Axelson-Berry

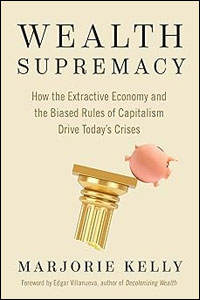

Wealth Supremacy: How the Extractive Economy and the Biased Rules of Capitalism Drive Today’s Crises by Marjorie Kelly with foreword by Edgar Villaneuva. (Berrett Koehler Publishers, 2023.)

| Kelly gives us a vocabulary for understanding something that many Indy readers, including myself, have always known and bemoaned but never articulated and never thought we could change: that the system we live in is all about more money and that the finance sector of the economy is out of control. It won’t be long before air is traded on the stock market among shareholders who believe in more, more, more, even if they consider themselves reasonable and activist in many ways. This isn’t about capitalism or socialism, it isn’t about ownership: it’s about the tenet that money (finance) has to be the shared goal. Kelly, who lives in the Boston area and has Valley connections, highlights alternative economic models already in place that can form the foundations of a new, more democratic economic, and offers pathways we can take to get there. The book blurb puts it better, saying that Kelly’s book is “[a] powerful analysis of how the bias towards wealth that is woven into the very fabric of American capitalism is damaging people, the economy, and the planet, and what the foundations of a new economy could be… This bold manifesto exposes seven myths underlying wealth supremacy, the bias that institutionalizes infinite extraction of wealth by and for the wealthy, and is the hidden force behind economic injustice, the climate crisis, and so many other problems of our day.” Here are the seven myths, taken from the table of contents: The Myth of Maximizing (no amount of wealth is ever enough) The Myth of Fiduciary Duty (expanding wealth is a sacred obligation) It’s About Extracting From the Rest of Us (this is the unseen underside of wealth and wealth-building) The Myths of Corporate Government and the Income Statement (workers aren’t members of the corporation) The Myth of Materiality (ecological and societal damages aren’t real) The Myth of the Free Market and Takings (the first duty of government is to protect wealth A Society Half plutocratic, Half democratic (the crisis of democracy) |

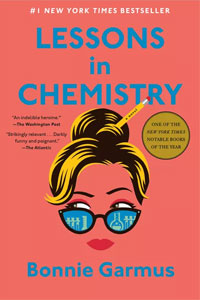

Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus. (Doubleday, 2022.)

| In these worrisome times, Lessons in Chemistry is a relief to read, vibrant and refreshing. It is a send-off on the 1950s — midcentury woes of women and others who didn’t count — from the perspective of a female scientist when women were considered threats, the mothers of your children, or sex objects, all of whom had to be destroyed by ridicule and bullying if they didn’t keep their heads down. I haven’t laughed so much in ages, as Garmus shows how ridiculous our society was/is/will be, with loads of compassion and humor. Essentially, a brilliant female scientist, Elizabeth Gott, is subjected to research theft and other forms of sociopathic ill treatment at the hands of her fellow scientists at a prominent research institute. The ill-treatment is held at bay due to her marriage to a scary-brilliant scientist, but then he dies in an accident, and she is suddenly a single mother, rapidly unemployed, but a fantastic manager and cook, which brings her to the attention of a TV exec who lives in the same town. She accepts a job creating a television cooking show, and she and the show become stars because she’s got tons of charisma and knowledge but even more so because she provides no-nonsense throw-offs about personal empowerment, child-raising, activism, and chemistry of course, besides the recipes. If you want a good, funny, light read that will inspire you to take some chemistry classes and get stricter with your kids, this is a good one. |

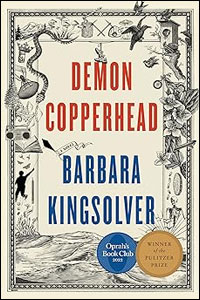

Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver. (Harper Collins, 2022.)

| Barbara Kingsolver has added immensely to my knowledge and understanding of drug and alcohol addiction, especially in the context of low-income rural life today. Like too many others in Amherst, I imagine, I’ve been recently experiencing an opportunity to help a grandchild actively engaged in being clean and sober, meaning completely drug and alcohol free, an addict in recovery. In ways large and small, as a result of Kingsolver’s book I’m able to educate the whole family so that all of us better understand addiction and can share in the support for this beloved young man. Indy readers probably know the story line already — after all, it got the Pulitzer in fiction in 2023 — about a poverty-stricken Appalachian kid (in a dysfunctional family with addiction problems, followed by foster care with other problems) who has excellent potential but falls into medically-induced addiction with disastrous results, and eventually…. well, no spoilers. Heartfelt thanks to Barbara Kingsolver. |

Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World by Naomi Klein (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2023.)

| This book has two main strands —one concerns the phenomenon of the doppelganger, “an apparition or double of a living person ” (from Oxford Languages, courtesy of Google), and the other concerns a different type of doppelganger: the culture today in which conspiracy-minded right-wingers and conspiracy-minded segments of the leftwing are doppelgangers, believing that every COVID vaccination is the U.S. government implanting digital spyware in the global population, that it doesn’t matter if Biden or a rightwing fascist type is elected, that the governments of China and Russia don’t cause wars or conduct ethnic cleansing, and that Steve Bannon is a brilliant leader. Klein is in a position to dissect both, as her own doppelganger, Naomi Wolf, famous long ago for investigating corporate power over female beauty standards, is now as-good-as on Bannon’s bandwagon and staff. Klein notes that once-vibrant debate has given way to fiercely policed, binary speech and group identities are now built around rigid insider/outsider dichotomies. Klein doesn’t ignore real conspiracies, by the way, and is ardent about continuing to confront them. Her section on Zionism and the doppelganger relationship between Israelis and Palestinians is especially fascinating: “As for those not directly affected by this struggle, it would help if more conversations could hold greater complexity—the ability to ackowledge that the Israelis who came to Palestine in the 1940s were survivors of genocide…and that they were settler colonists who participated in the ethnic cleansing of another people. That they were victims of white supremacy in Europe [who were] passed the mantle of whiteness in Palestine. That [they] are nationalists in their own right and that their country has long been enlisted by the United States to act as a kind of subcontracted military base in the region. All of this is true all at once. Contradictions like these don’t fit comfortably within the usual binaries….” |

Art Keene

How The Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America, by Clint Smith. (Little, Brown and Company, 2021.)

| Beginning in his hometown of New Orleans, Smith leads the reader on a tour of historical monuments, landmarks, and living history museums that offers an intergenerational story of how slavery has been central in shaping our nation’s collective history, and ourselves. Smith speaks with docents, historical re-enactors, and the visitors to these historic sites to interrogate the stories that are told about slavery and it’s legacy and the impact of those stories on our present lives. Smith, a poet, offers us rich, captivating, and accessible prose that forces us to consider hard questions about the legacy of slavery in our nation that we might otherwise choose to avoid. This was by far my favorite read of the last year. Winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award for Nonfiction and a NYT top ten book for 2021. |

Apeirogon, by Colum McCann. (Harper Collins, 2020.)

| Just about everyone in our family read this book back in 2020 and we recommended it in the Indy that year. I reprise that recommendation here because of the ongoing war in Gaza. This is a novel based on the real-life deep friendship of an Israeli and a Palestinian, who have each lost a daughter in the conflict between their peoples. The two men are members of the group Combatants for Peace who speak around the world in support of a peaceful solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and have recently been seen on major media outlets speaking out against genocide and the war crimes of both sides and underscoring a message that only justice for all peoples can bring peace to the region and the world. (The group made a presentation in Amherst several years ago). Maura and I (who have both spent years working in this region) found this book to be comforting, reminding us that there are alternatives to war and to the growing calls to embrace hatred and retribution and that there are people actively engaged in the seemingly hopeless work of building a better world, even amid a conflagration. The writing form is experimental with some chapters only a few words long – an homage perhaps to 1001 Arabian nights, so it might not be for everyone. But we found it to be a compelling read then and well worth revisiting with the ongoing war. Nominated for several international awards including the Booker Prize. |

Our Missing Hearts, by Celeste Ng. (Penguin 2022.)

| This dystopian tale is set in a fascist New York City, perhaps a few decades from now, and portrays life under a severe regime where children of “subversives” are removed from their homes and reassigned to trusted families. It tells the story of a young boy whose mother, a Chinese poet, disappeared suddenly when he was nine years old, the efforts of his father, a deposed university professor, to protect him and avoid running afoul of the government, and his efforts, assisted by a network of underground librarians, to find out what happened to her. The book is an undisguised commentary on our own era, giving us both a frightening picture of where we might be headed and a reminder of the capacity of the human spirit to resist. |

The Deadly Rise of Anti-science: A Scientist’s Warning by Peter J. Hotez. (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2023.)

| This book, essentially a memoir of how vaccine scientist Hotez has been demonized for decades by anti-vaccine zealots, shows how the anti-vaccine movement has evolved from an effort focused on disseminating health disinformation to become an essential element of extremist politics. This slim volume documents the rise of the anti-vaccine movement in America and its integration into far-right politics. Hotez, whose resume includes the development of a free COVID-19 vaccine for developing countries, documents his own career-long harassment by the movement, which intensified during the COVID-19 epidemic when the anti-vaccine crowd labeled him (along with CDC director Anthony Fauci and other public health officials), a public enemy and called for his execution. That national vilification by outlets like Fox News and Meta, produced a slew of death threats against Hotez and his family. The book provides a clear picture of how the anti-vax movement has become integral to right wing politics and how social and corporate media have been instrumental in disseminating disinformation about vaccines while demonizing those who do the research and promote public health. The book lacks a political analysis of why the movement has gained so much traction at this particular moment. But it does provide a clear and sobering picture for how the war on vaccines – and by extension, on science–has taken root in this country, and offers a warning about the dangerous places that this can take us. |

Maura Keene

Victory City, by Salman Rushdie. (Random House, 2023.)

| Although I am usually not a fan of magical realism, I make an exception for Rushdie. Victory City is written as an ancient parable telling the story of Pampa Kampana, a nine-year old prophet who tries to create a women-led just society, but must keep reinventing it when people keep messing it up. She was given special powers that caused her to age slowly by a goddess who visited her after her mother and all the women of her small kingdom immolated themselves. The New York Times review sets the scene for the novel: Pampa Kampana’s tale begins when her mother walks into the flames. “The story goes” that with all their husbands dead in battle, the women of a small and ruined kingdom built a bonfire on the banks of a river, “said farewell to one another” and silently stepped into death. The “cannibal pungency” of their burning also smelled of sandalwood and cloves, and afterward Pampa could never bring herself to eat meat, not once in all her remaining 238 years, during which she was three times a queen and aged so slowly that she looked younger than her own great-granddaughters many times removed. But she was just 9 when her mother died, and as she wandered away from the flames she was visited by the goddess whose name she bore. What follows is a fascinating a beautifully written tale of the attempt to create a just society. Pampa’s suffering at the hands of those who try to gain power is made all the more poignant by the real-life attack on Rushdie in August, 2022. This is an outstanding novel that inspires much reflection on the state of the world. |

The Covenant of Water, by Abraham Verghese. (Grove Press, 2023.)

| Sticking with the dive into Indian history, Verghese follows three generations of a family in Kerala, Southern India led by the extraordinary matriarch Big Ammachi. The family possesses an unusual affliction in that many of its members have died by drowning. The novel embraces the years 1900-1977 and all the changes, both local and in the Indian nation, that the history encompasses. In beautiful prose, Verghese describes tragedies and loving relationships, weaving them with the advances in medical science occurring around them. The 700 pages of the novel are over too soon. The Covenant of Water is a worthy successor to Verghese’s first novel Cutting for Stone and his medical memoirs The Tennis Partner and My Own Country. All are excellent reads. |

Jeff Lee

A Libertarian Walks Into a Bear: The Utopian Plot to Liberate an American Town (And Some Bears) by Matthew Hongoltz-Hetling (PublicAffairs, 2020.)

| In 2004 a prominent libertarian from Grafton, NH decided that his hometown, with its limited zoning laws and situated in the “Live Free or Die” state would be a proper haven for small-government advocates from around the country. A call went out and hundreds answered. Soon a libertarian tent-city sprang up and the small town’s government became permeated by extreme libertarian philosophy. Garbage went uncollected and public health rules unenforced, allowing a population of aggressive black bears to join the libertarians in migrating to Grafton. The result was the first bear attack on a human in New Hampshire in 100 years. Hongoltz-Hetling’s account of Grafton’s plight reminds us of the fragility of democracy and how in this digital age it is not difficult for a special interest group to dominate the politics of a small town. |

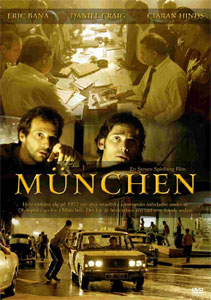

Munich, Directed by Stephen Speilberg (Universal Pictures, Dreamworks SKG, 2005.)

| Not a book but a film directed by Stephen Speilberg, co-written by Tony Kushner and Eric Roth and loosely based on a 1984 book titled Vengeance by George Jonas. In a recent New York Times essay, film critic Lisa Schwarzbaum spotlighted Munich, asserting that The Best Movie About Israel and Gaza Now Came Out 18 Years Ago. I can’t disagree. In 1972 the world was horrified when a Palestinian group known as Black September captured 11 Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympic Games and all were ultimately murdered during an attempt by German authorities to free them. Munich is a semi-fictionalized account of how a Mossad cell was tasked by Israel to track down and assassinate the Black September perpetrators. They ultimately succeeded in killing nine, but the toll it took on the Mossad agents, their growing misgivings, and the failure to reduce the conflict between Palestinians and Israelis is an unescapable message. While Speilberg has called the film his “prayer for peace,” he has been condemned for drawing a “moral equvalence” between the Palestinian terrorists and the Mossad agents. What is clear is that the cycle of violence and vengeance precipitated by the Munich horror has only grown unabated. |

Other “Best of” Lists for 2023

Lit Hub:

The Ultimate Best Books Of 2023 List (a compilation of all of the best, “best of” lists)

The Best Reviewed Fiction of 2023

The Best Reviewed Non-fiction of 2023

Science Fiction and Fantasy:

The Best Science Fiction of 2023: The Arthur C. Clarke Award Finalists

The 2023 Hugo Award Winners

The 2023 Nebula Award Finalists

Washington Post 10 Best Science Fiction and Fantasy Novels 2023

Polygon’s Best SciFi and Fantasy Books of 2023

The Atlantic:

The Atlantic 10: The Ten Best Books of 2023

The Booker Prize:

Booker Prize Long and Short Lists for 2023

The Guardian:

Best Books of 2023

The Jones Library

Most Borrowed Books at the Jones Library in 2023

Mother Jones Magazine:

The 29 Books We Couldn’t Stop Thinking About in 2023

The New Yorker:

Best Books of 2023

The New York Times:

The 10 Best Books of 2023

100 Notable Books of 2023

Progressive Magazine:

Our Favorite Books of 2023

Scientific American:

55 Recommended Science Books for 2023

Vox:

The Very Best Books of 2023

Thanks to the editors and reviewers for their choices and their insightful comments.

In the same spirit, could I suggest another category: Good Re-reads. For those concerned about the fate of democracy – or perhaps more pointedly the possibility of democracy – two essential texts read differently in 2023 than when I first read and taught them decades ago.

Thucydides’ The Peloponnesian War was written 2500 years ago to warn us about one way in which democracies can fail. Athens – wealthy, powerful and arrogant – lost sight of virtue in its lust for power and glory. People read Pericles’ Funeral Oration in praise of Athenian democracy but we would do better to heed the Athenians’ explanation to the conquered island of Melos: the strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must. Ultimately Athens lost everything.

Alexis de Tocqueville wrote Democracy in America almost 200 years ago. He wrote neither to warn nor to praise but perhaps to sigh. Tocqueville was an aristocrat whose parents came within minutes of losing their heads to the guillotine during the French Revolution. He didn’t really think democracy was good; he thought it was inevitable. His razor-sharp observation of how it worked, especially on the rapidly expanding frontier should give us real pause, since most of us grew up thinking democracy is inevitable too. Tocqueville’s picture is familiar but not comforting.

Thucydides noted both enslavement and murder as rights of victorious democracies. Tocqueville abhorred them but noted how comfortably they sat with the particular kind of religiosity that was unique to frontier America.

Both of these works should be required reading in 2024 – in America and elsewhere.