The Railways in Amherst

Amherst Railroad Station, 1898. Photo: Courtesy: Jones Library, Amherst, Massachusetts.

Amherst History Month by Month

“Now I’ve been crying lately, thinking about the world as it is/ Why must we go on hating, why can’t we live in bliss? / ‘Cause out on the edge of darkness, there rides a peace train/ Oh, peace train take this country, come take me home again.” Peace Train by Yusuf/Cat Stevens, 1971

Last week I was babysitting in Shelburne Falls. You know this already, gentle reader but it’s a village on the Deerfield River uniting the towns of Buckland and Shelburne a little north of Amherst. It is a destination kind of town, with many things to see and do, and often picked as a film location. It has a great Trolley Museum as well as the renowned tourist attraction known as the Bridge of Flowers, created from the actual trolley bridge that spans the river. You can still ride a trolley here, certain times of the year and from the windows of the car see great views of the town, nestled as it is into the valley.

Shelburne Falls, like Amherst, is a place still very much defined by transportation and specifically by the railroad. Each day, trains (of the goods and freight variety) trundle through town and the loud whistle is legendary if you live nearby. While I was babysitting, it all got me thinking again about railways in Amherst and also, about Cinda Jones’s great archive about the trolley system here, too. So a little exploration follows about trains and train architecture in our town.

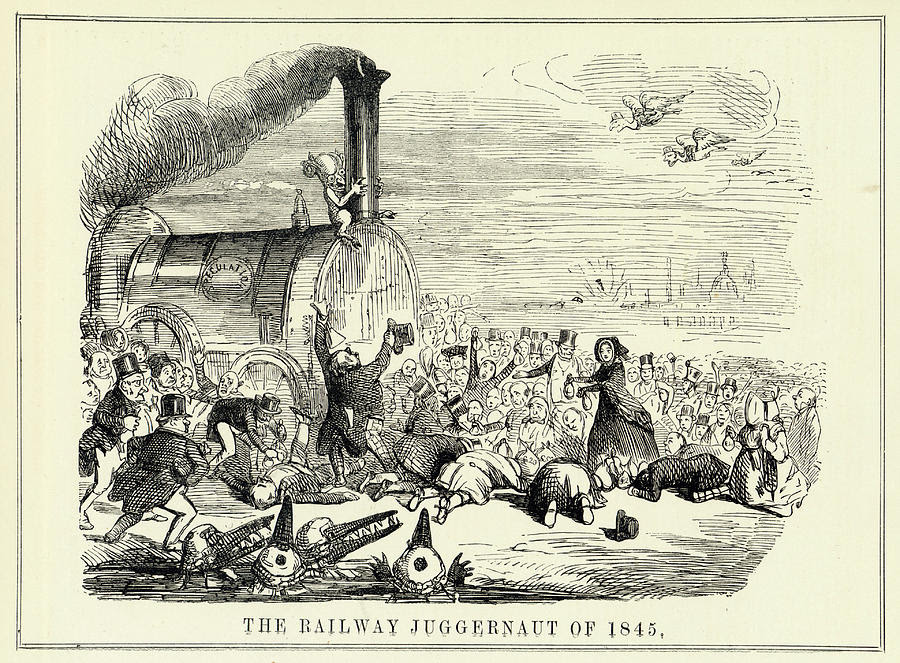

The railroad system in our country is probably one of the most defining physical dimensions of North America’s industrial age. This definitive “iron-horse” was met with fear and understandable alarm in indigenous communities, but the same rails were seen as agents of progress (progress being that very Victorian value) by 19th century entrepreneurs. In Europe, critics viewed the juggernaut of locomotive power and the railway network as an economic disaster waiting to happen, with speculators ready to devour the savings of people of modest means, who might be conned into support for the “Great Railway God.”

By 1883, American railroad companies had instituted time zones nationwide for safety. This standardization of time was seen as necessary for coordinating complex transit and freight schedules and ensuring safe, efficient travel for people across the time zones of this county. But it also had the effect of regulating other things in society as well.

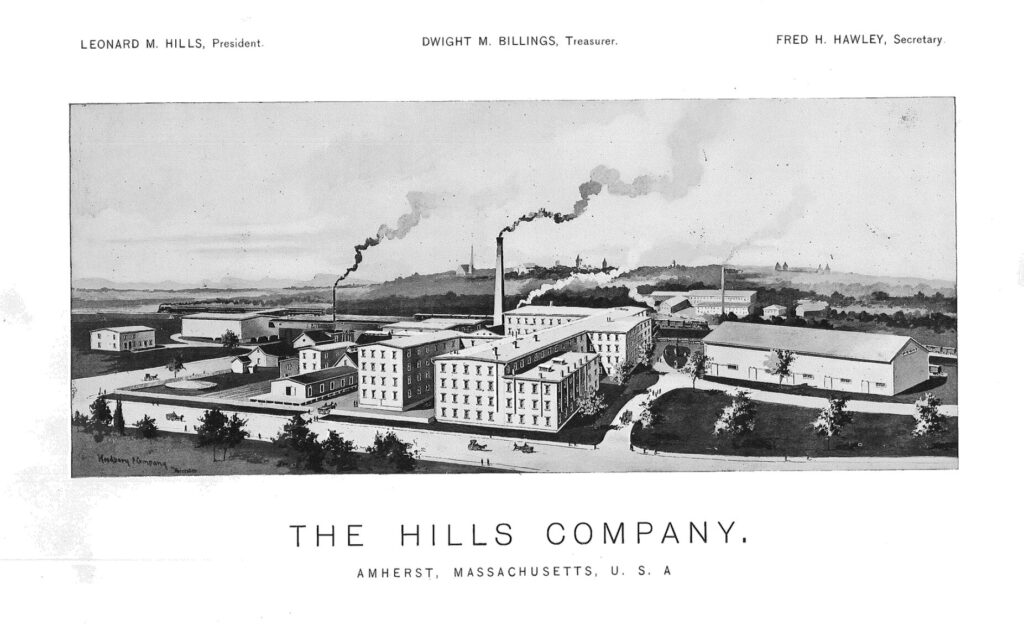

In Amherst, new enterprises grew up alongside the railroad stations and its transit systems (rail and trolley lines, along with existing waterways) soon connected Amherst literally to the world. It had been in the 1830s-1840s that the Dickinson family invested in Amherst’s railroad, encouraging it to come close by to what came to be known as “The Crossing,” situated near the Homestead and the Evergreens. The station was also very handy for the Hills Manufacturing company down the street. This new factory site was on the corner of College and Railroad Streets and was the largest palm leaf hat making factory in the US, started in 1829 by Leonard Mariner Hills. In line with the industrialized world of work where textiles were spun from thread woven in a factory rather than made by men and women in a home setting, (begun in Pawtucket, Rhode Island), the Hills Company revolutionized hat making by completing all the steps needed to make hats in multiples in a mill setting using a largely female workforce rather than making hats at home.

In Dwight, once known as Logtown, a little place on the road to Belchertown, a man named Lafayette Goodell – whose family had moved up here from Connecticut in 1777 – wanted to find a way to invigorate his father’s failing farm. In 1868, he invested twenty-five dollars in a flower seed business and with Wesley, his brother, created a destination called Pansy Park – a cluster of greenhouses and ornamental ponds – hoping to attract customers to the farm (later, the site became the Dwight Mini Mart, then a food establishment called Blubby’s). Visitors came by rail to Pansy Park, stopping at Dwight Station, to see plants and flowers from around the world. The business grew from 200 customers to 50,000.

Route 9 and South East Street are the best locations today from which to access and experience some of Amherst’s best old railway lines that are now recreational bike and walking trail systems that have sort-of upcycled the railroad beds underneath them. These include the Norwottuck Branch Rail Trail, that is part of the Mass Central Rail Trail, which begins in Dwight village, roughly where Montague Brook and the Central New England Railroad crosses Warren Wright Road, a road that goes from the edge of Amherst into Belchertown. The Town of Amherst accesses some of our drinking water wells from the Lawrence Swamp wetlands and waterways between Station Rd in Amherst and Warren Wright Road in Belchertown. (Thanks here to Rod Kusner for his knowledge of this topic.) It would assist our climate crisis if our bike trails could be more convenient for work and commercial destinations along with offering us all recreational outings/exercise.

What remains of Amherst’s original railroad buildings includes the very handsome Amherst railway station off Main Street (that was most recently a yoga studio)

and various stone bridge-abutments and culverts for diverting any waterway from the tracks. The Amherst Farmers Supply, founded in 1945 on South Pleasant Street occupies one of the buildings once of service to the railroad, that has been transformed carefully into the store. It sits right by the bike trail, off Route 116.

A death knell of the railway system was the Hurricane of 1938 that washed out many local bridges and sections of track east of the Quabbin Reservoir, hence “severing rail service in the east from service in the west.” (Kusner) The demise of railway travel is a topic larger than is possible for this column. One of the other remaining railroad buildings on bike trail in Hadley that used to be occupied by Trailside Cycles is now a wonderful pinball parlor and video arcade named The Quarters.

I think the author is confusing two railroads — the north/south railroad which still exists (and which Amtrak used until recently) and the east/west railroad which is now the bike trail.

There were three east/west rail lines from Boston — they followed (approximately) Route 2, Route 9, and the Mass Pike/Route 20. I believe the latter was the Boston & Albany which is why it went into South Station and why any train from Springfield will have to go to South Station. (The B&M built/used North Station to make it more difficult for anyone to take them over.)

As of 1875, the northern route, which followed Route 2, had the Hoosac Tunnel which was a major asset over all the other railroad lines on the east coast. By the 1930s, the Boston & Maine RR owned both this line *and* the line that is now the rail trail, but because of the tunnel, they were putting all their money into that line. They still had the line through Amherst so they used it, but it very much was a secondary line — and moreso once the Quabbin flooded those towns.

So when the tracks washed out in 1938, what the B&M decided was that it was cheaper to serve Amherst by going the long way from Greenfield down to Northamption and then coming back to Amherst, and as late as the 1970s they still delivered to Amherst Farmer’s Supply. (I suspect they once did to the Hadley Garden Center as well.) Heavy stuff that once had to be shipped by rail.

Amherst Farmer’s Supply receipts list their official address as “B& M Station” — I believe that their store was the passenger station and their storage sheds were the B&M freight sheds. There still is a railroad track on the south side of the sheds (most of it buried in crushed stone) and you can see where it went out to join what is now the bike trail. There is (or was) a semaphore signal on the north side of the store building.

The other thing to remember is that I believe that Main Street was the original Route 9 and that it had to be relocated because of the Quabbin. If you follow it up to Pelham, beyond 202 it becomes a dirt road that goes down into the Quabbin, and I remember that Pelham ran into hazmat problems building their elementary school in the ’90s because of the historical road. And the current alignment may predate the Quabbin.

Since writing this article and the one on the trolley system, it appears that there are some really knowledgeable folks out there with very interesting information and perspectives to share. Perhaps they might submit articles themselves.

We and knowledge evolve. I did come to find out (the awful phrase, ‘come-to-find-out’ rolling my eyes, emoticon!) that there was a railroad station actually at Pansy Park as well as the one at Dwight. https://www.nepm.org/commentary/2023-05-23/pansy-park-put-dwight-on-the-map-in-the-late-1800s.

https://www.gazettenet.com/Railroad-Connected-Pioneer-Valley-to-World-51013261

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dwight,_Massachusetts

Look for Dwight Day June 15, 2024!

I happened to see this little movie for the last Vermonter train running/stopping in Amherst and its in the link below. https://youtu.be/bYshDyv9DrM?feature=shared

The railroad station is now home to a new business in Amherst called BrickHouse Spin. https://brickhousespin.com/