Report on the Meeting Between Student Negotiators and UMass Amherst Administration, May 7, 2024

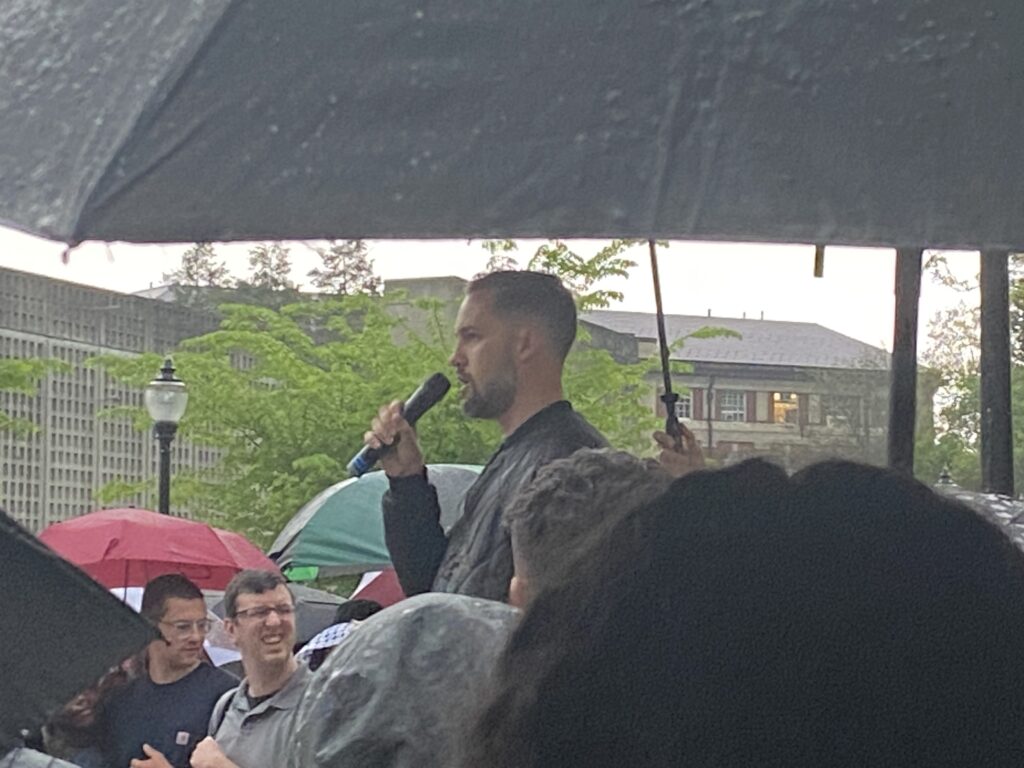

UMass History Professor Kevin Young address the Rally for Rafah at the UMass Student Union on May 7, 2024. Photo: Art Keene

Given what I witnessed on May 7–8, I must conclude that the Chancellor engaged in bad-faith negotiations with the students, and that his May 7 email was a self-serving attempt to discredit the student negotiators and protesters in order to justify the repressive response that he had just set in motion.

Context

On May 7 at approximately 4:30 p.m., three student negotiators and the author met with Chancellor Reyes and other administrators to discuss the demands of the student-led solidarity encampment for Gaza, which was then located on the lawn between the Du Bois library and the campus pond. The meeting took place several hours after the reestablishment of the encampment. The original encampment had been established in the early morning of April 29, but was dismantled by the students after administrators threatened them with arrest and/or disciplinary action.

Student negotiators included two undergraduates from Students for Justice in Palestine and one member of the Graduate Employee Organization’s Palestine Solidarity Caucus. I was invited to attend as a representative of Faculty for Justice in Palestine. However, because I had played no role in formulating the students’ demands or in organizing the encampment, my primary role in the meeting was as a note-taker and faculty witness. I typed detailed notes, including verbatim or near-verbatim transcriptions of much of the dialogue. I spoke only once, toward the end.

Present from the administration side were Chancellor Javier Reyes, Chief of Staff Rolanda Burney, Interim Provost Mike Malone, Vice Chancellor for University Relations John Kennedy, Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs and Campus Life Shelly Perdomo-Ahmed, and Deputy General Counsel Brian Burke.

The students presented four demands, which they had sent to the administration prior to the meeting. These demands were slightly updated versions of their longstanding public demands.

- “UMass DISCLOSE, on the UMass website, all direct and indirect partnerships with war profiteers, defense contractors, and all corporations affiliated with Israel, and entities on the B.D.S. list…”

- “DIVEST from war profiteers (i.e. RTX, General Dynamics, DSC Corp), and entities on the B.D.S. focus list…”

- “CUT TIES with Raytheon and Study Abroad Programs with Israel…”

- “The UMass Dean of Students Office and the Student Code of Conduct Office DROP THE SANCTIONS AND CHARGES against the 57 students arrested during the Whitmore sit-in last October…”

The first three of these items included several sub-points elaborating in more detail what the implementation of these actions would entail.

Summary

At the start of the meeting Chancellor Reyes issued an ultimatum: that the students must “take down the encampment” before dialogue on any demands could continue. Midway through the meeting he reiterated that “I can’t do anything else if the encampment is there.” He characterized the encampment as a threat to campus safety and justified the dismantlement order based on the students’ violation of the land-use policy.

The Chancellor repeatedly claimed that he has no power to address any of the students’ demands. He said he had been advocating behind the scenes for the UMass Board of Trustees and UMass Foundation to consider students’ divestment proposal. But “with respect to the rest of the demands, there’s nothing that I can do,” he said.

In response, the student negotiators pointed out three areas where Chancellor Reyes does have personal power to address their demands:

- He has the power to overturn the rulings of lower-level UMass Amherst officials against the students who engaged in peaceful protest at the Whitmore administration building on October 25, 2023. Section 5.4.3 of the Code of Student Conduct unambiguously states that the Chancellor “may use professional discretion” to “overturn the decision” of lower officials. He has thus had the power to do so for many months, at least since the conclusion of Student Conduct hearings in late 2023. The students noted that Chancellor Reyes has erroneously claimed, on multiple occasions, that the Code of Student Conduct requires students to submit individual requests for dismissal of charges directly to him before he can review any decisions by lower officials. The aforementioned section of the Code stipulates no such thing, and in any case, Chancellor Reyes has been the recipient of numerous petitions, emails, and verbal communications since October 25, calling upon him to “drop the charges” against the arrested students. The Chancellor did not acknowledge his false claim, instead saying merely, “We are going through the process. It takes time … There is a process that can’t be circumvented.” The students replied, “There is no process outlined in the Code of Conduct.” He did not respond to this point and instead doubled down: “I need to look at all the evidence … I have been following that process.” He still did not cite the specific provision of the Code to which he was referring.

- Although he can’t unilaterally declare divestment from war profiteers, he could issue a public statement advocating that the UMass Foundation do so. When pressed on that point, he finally admitted that he simply did not want to issue such a statement since it would upset some people. I said that UMass’s partial divestment from fossil fuels in 2016 had upset some people too, but that being a leader means acting with integrity and doing the right thing even if not everyone agrees. He appeared unimpressed at this comment.

- He has the power to exclude recruiters from companies associated with systematic violations of the law. The students cited the NACE Principles to which UMass Amherst subscribes, which stipulate that recruiters must “comply with laws associated with local, state, and federal entities.” Raytheon’s “weapons are being used to violate international laws,” said one of the students. (International laws to which the United States is a signatory take precedent over U.S. domestic law under Article 6 of the Constitution. In addition, the provision of weaponry to military forces engaged in “gross violations of human rights” has been a violation of U.S. domestic laws since the U.S. Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (22 U.S.C. § 2378d and 10 U.S.C. § 2249e). The Chancellor replied that he cannot render judgment on that question because he’s not a legal expert. When students replied that the International Court of Justice has issued pronouncements on the illegality of US and Israeli policies, he did not respond. He said instead, “What would be amazing is to present that in a conference.”

It is worth noting that, upon student questioning, Chancellor Reyes did acknowledge his own power at several points in the meeting: 1) when he admitted that he did not wish to issue a statement of support for divestment, 2) when he conceded that he holds authority over the UMass Police Department (UMPD), and 3) when he said, “I can’t do anything else if the encampment is there.” This last statement implicitly admitted that he was making a choice not to concede to student demands as long as the students maintained the encampment.

Shortly after 5:00 p.m., an attorney who works with the students entered the negotiations meeting to report that UMPD and riot officers from the Massachusetts State Police had amassed at a staging area near the encampment. The Chancellor did not appear surprised at this news. Forced to admit that he had ordered the police deployment, he then reassured the student negotiators that “they’re not going to intervene” while the negotiating meeting was continuing – “at the moment.” Given the timing of the meeting and the timing of the police arrival, it appears likely that the Chancellor had ordered the deployment before he entered the meeting. He had apparently resolved to deploy the police against the protesters if the student negotiators did not agree to his ultimatum. This inference is supported by the attorney’s subsequent conversation with Deputy Chief Damian DeWolf at the site of police presence. As the attorney reported to me afterward, “I asked him if he knew that there were negotiations going on. He said that he knew the negotiations were going on, and that hopefully ‘the right decision’ would be made by the students.”

The location that the administration chose for the negotiations meeting was also curious: Draper Hall, which is situated at a significant distance north of the encampment and in the opposite direction from where police were amassing to the south of the encampment. The natural location for a meeting would have been the Whitmore administration building. However, a meeting in Whitmore – south of the encampment – would have risked the police presence being visible to the student negotiators. It appears in retrospect that administrators chose Draper Hall because it was located far from the location where police were amassing.

This evidence of bad faith only increased the students’ distrust of the Chancellor. They felt they had been lured to a meeting under false pretenses, and at a location that impeded their ability to be aware of what was happening outside. Had they known of the police deployment, they may or may not have agreed to the meeting.

After the negotiations broke down, Chancellor Reyes sent an email to the full campus. The email presented a misleading picture of the administration’s and the student negotiators’ respective positions. Among the inaccurate passages are the following:

- “Involving law enforcement is the absolute last resort.” As the students pointed out to him, some campus leaders across the United States have responded to encampments with good-faith negotiations. Not all of those campus leaders have agreed to student demands, but even in those cases some have chosen the option of allowing the encampments to continue. There is no reason Chancellor Reyes could not have chosen the same option.

- “I asked the University of Massachusetts Police Department to begin dispersing the crowd and dismantling the encampment.” The Chancellor’s reference to police omitted the fact that the Massachusetts State Police, not simply UMPD, had been summoned. State Police in riot gear were apparently responsible for most (but by no means all) of the police violence captured on video the night of May 7–8.

- “The students rejected these offers…” Chancellor Reyes wrote, “I also shared with the students that the Board of Trustees has agreed to consider the UMass Amherst student trustee’s petition calling for divestment from defense-related firms at their next board meeting in June. The UMass Foundation Board, which manages the university’s endowment, also received a request to consider divestment. The students rejected these offers from the campus and the Board of Trustees.” The student negotiators did not reject those offers. On the contrary, they supported the student trustee’s divestment resolution and sought information from the administration about how they could meaningfully participate in the June 7 Board of Trustees meeting. They did say that merely having the item on the Board of Trustees meeting agenda would probably not be enough to convince the campers to dismantle the encampment. They wanted public advocacy by the Chancellor for divestment and the guarantee of a meaningful opportunity to participate in the June 7 meeting – in addition to an immediate dropping of all charges against protesters, disclosure of all investments and business ties, and a severing of the campus’s relationships with weapons companies and study-abroad programs in Israel.

The above is not an exhaustive summary. For other details of the meeting, see my typewritten notes.

Analysis

The student negotiators came to the meeting prepared to negotiate. Unfortunately Chancellor Reyes did not. The students were willing to cede some ground on the details, and they acknowledged that the Chancellor did not have the personal power to grant all their demands himself. But they did expect a good-faith meeting and major, verifiable movement toward their key demands. They cited the examples of other colleges and universities whose leaders have sought to address students’ concerns and/or refrained from arresting nonviolent protesters at tent encampments.

My guess is that the student negotiators would have recommended that protesters dismantle the encampment had Chancellor Reyes proven that he was truly doing everything within his personal power to meet the demands mentioned in the last bullet point above: public advocacy by the Chancellor for divestment, the guarantee of an opportunity for students to participate in the June 7 Board of Trustees meeting, immediate dropping of all charges against protesters, disclosure of all investments and business ties, and a severing of the UMass Amherst campus’s relationships with weapons companies and study-abroad programs in Israel. Chancellor Reyes could have granted most of those demands immediately or committed in writing to fulfilling them in the near future.

I must note that I cannot know for sure what the students – either the negotiators or the protesters outside – would have accepted. Students’ willingness to negotiate was partly contingent on their perception of good faith on the other side of the table. The atmosphere in the meeting was poisoned from the outset by the Chancellor’s lack of good faith and by the condescending manner in which he and several members of his team spoke to the student negotiators. The Palestinian student negotiator was repeatedly interrupted by the Chancellor and once by Chief of Staff Burney (though Chief of Staff Burney later apologized). This behavior dimmed the chances of any negotiated settlement. The larger context of administration-student relations also matters. The Reyes administration has consistently treated student protesters with disrespect, which has contributed to widespread distrust among the students.

In both the meeting and his subsequent email to the campus, Chancellor Reyes portrayed the students as impetuous and intransigent. This characterization doesn’t square with what I witnessed in the meeting. The student negotiators were well informed, organized, and committed to negotiating in good faith. They sought a peaceful and legal resolution of their concerns.

Furthermore, not one of the students whom I met at the encampment or in jail struck me as motivated by a quest for thrills or unnecessary confrontation with the UMass administration. Contrary to the sneer sometimes heard in relation to the students arrested on October 25 – “Well, didn’t they want to get arrested?” – I did not speak with any students who appeared eager or excited to get arrested on May 7. All seemed to me acutely conscious of the moral cause for which they were struggling, and reluctant but willing to incur potential risks to their persons and their futures in pursuit of that cause.

Given what I witnessed on May 7–8, I must conclude that the Chancellor engaged in bad-faith negotiations with the students, and that his May 7 email was a self-serving attempt to discredit the student negotiators and protesters in order to justify the repressive response that he had just set in motion.

Kevin A. Young

Associate Professor of History, UMass Amherst

May 9, 2024