The Generation that Says No More: Inside the Columbia University Encampments for Palestine

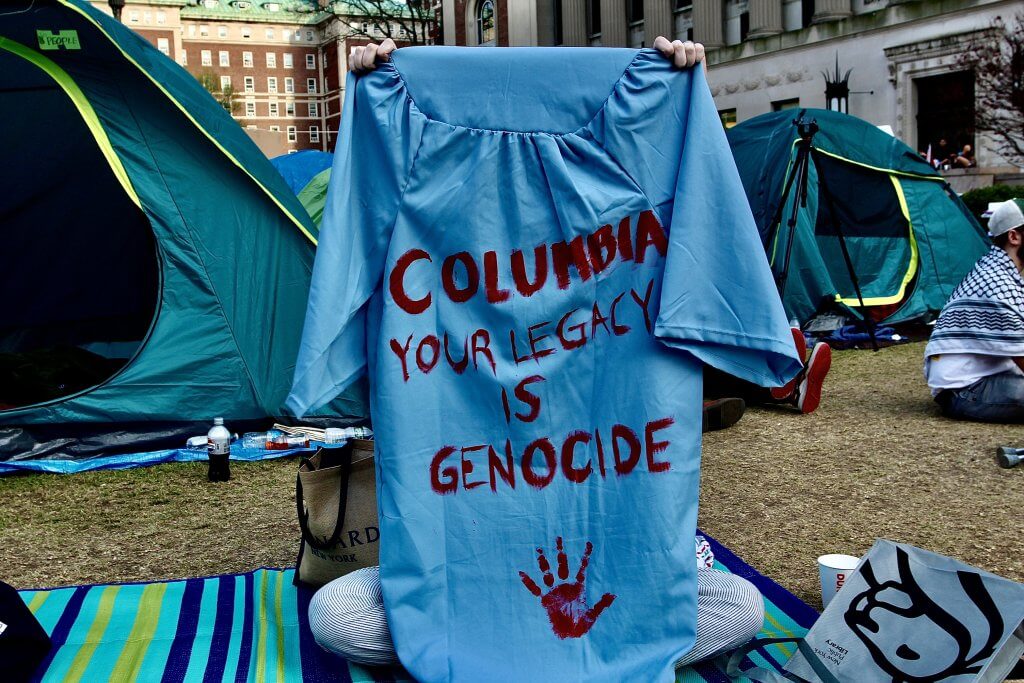

STUDENTS AT COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PROTEST FOR DIVESTMENT DURING THE ENCAMPMENT FOR GAZA, APRIL 2024 (PHOTO: HODA SHERIF)

A Better World is Possible

The following article, “The Generation that Says No More: Inside the Columbia University Encampments for Palestine” by Hoda Sherif, appeared originally in Mondoweiss on June 6, 2024. It is reposted here with permission.

Editor’s note: A couple of weeks ago, students who are part of the UMass Mutual Aid Project wrote in the pages of the Indy (see also here) about their efforts to enact new ways of being, asserting that, “Students at UMass—like an increasing number of communities—are rejecting the capitalist, modernist proposition that they are individuals whose essential responsibility is to themselves, and are instead carefully attending to and embracing their relational, interdependence with others.”

When I visited the first UMass encampment for Palestine on April 29, I saw these aspirations in action. I was struck by the volume and intensity of the mutual teaching and learning that was going on. I was taken by the obvious commitment of those assembled to take care of each other. I thought the atmosphere did not reflect despair or hopelessness in spite of the tragedy that had engendered the encampment and the threats of punishment coming from the university administration. Rather, I observed a palpable sense of possibility – a belief that there were pathways for repairing the world, and it looked to me like these students were exploring them and also trying to enact them in their day to day engagements with each other.

I get this same sense when reading Hoda Sherif’s account of the Columbia encampments where a profound solidarity was created and where students could see in their actions that they were creating in their collective endeavors, the elements of a different, more humane, better world. Near the end of her comprehensive account she observes, “Here was a lifestyle that could only be sustained through a relentless pursuit of caregiving – one that I saw firsthand: “What can I make you for lunch?” a student asks a Palestinian student draped in a keffiyeh walking with crutches. Close by, another student is in tears after a storytelling session deeply touched her, while two strangers embraced her, holding her hand. This was a radical reimagining of a society that promised to include everyone, manifested in every rallying call: Who keeps us safe? We keep us safe.” Art Keene

Headlines about mass graves and dark-site concentration camps filled with innocent Palestinian prisoners have become routine. Elementary schools and hospitals in Gaza are carpet bombed daily, hovering armed quadcopters mimicking the sounds of crying babies are documented for the world to see on Instagram live, and war drums are Palestinian babies’ newest bedtime stories. What about any of this is normal?

I’ve spent a great deal of time in each of the encampments constructed by students. Throughout, one lesson has become painstakingly clear: far from Gaza, on indifferent highways or unfamiliar streets of alien cities, many are not engaging with the ongoing horrors of this war each day as if it were the first. Then there are those whose existence is entirely consumed by it: our youth. Today it is them who teach, educate, and lead. And the lessons they’re imparting in these spaces surpasses the value of any classroom at any institution in this world.

On May 31, students associated with Jafra, a self-governing coalition of Palestinian students endorsed by Columbia University Apartheid Divest in conjunction with Students for Justice in Palestine and Columbia and Barnard’s Jewish Voice for Peace set up Columbia’s third Butler Lawn encampment since the occupation of Hamilton Hall and the arrests. Their new message: “We’re back bitches.”

The new encampment was to coincide perfectly with the Class of 2009’s Alumni weekend where formal attendees, clad in elegant gowns and tuxedos, raised champagne glasses at their festive reunion party, secured under a tent over at Low Plaza. Visiting alumni paid anywhere between $150 to $400 to take part. The goal of the reunion was to raise $125,000 for the Columbia College Fund.

Directly across the reunion party, which took place Saturday night, was the students’ latest encampment where the whirlwind of songs and chants pealed throughout every corner of campus. The songs reflected the multifaceted spirit of Palestine: exodus, passion, power through and with the people, irrepressibility, sorrow, anger, and of course, hope.

Like the encampment itself, the playlist became a time of looking back and looking forward. Tunes ranged from Gill Scott-Heron’s “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” an unapologetic wake-up call for the Black community to be active and not a passive participant in their freedom during the Civil Rights movement, to Macklemore’s “Hind’s Hall,” a recent release capturing the tenacity of students’ advocating for Gaza, notably Columbia students and their occupation of Hamilton Hall. Between the two songs and everything in between, it was a special reminder that students were not walking this path alone. That the fires of repression spread from the streets to their campus was one consistent with revolutionary legacies built on the historic battle of belonging, a struggle that required rejecting entire universities as the cogs that drive our neoliberal world order.

To anyone paying attention, the weekend presented only a mere snapshot of the decades’ long Palestinian struggle against the normalized vista of institutional and racial injustice. Many alumni stood in clusters, shouted hate speech or eyed the students as though they were alien. Some even stopped by to ask the students if they had received “permission to vandalize” the lawn.

On June 1, the first day of the newly-established encampment, the administration sent an email stating that the re-occupation “breaches University regulations” and that consistent with normal practice, “when vandalism occurs, NYPD, accompanied by Public Safety, [will be] on campus to photograph and document the damage as part of an investigation for criminal mischief.” The students’ demands, however, persisted just the same since the onset of the first encampment: divestment from Israeli-owned operations and companies, whether direct or indirect, and transparent disclosure of the university’s financial endeavors, with the exception of a new call for alumni to pause their pledged donations until Columbia disengages from complicity in the ongoing slaughter of thousands of Palestinians.

Here were the changemakers of our generation, repurposing their university resources to instruct themselves and one another to think – and rethink through crisis and devastation; to fight for the eradication of oppression in each of its forms, to preserve Palestinian life, indigenous sovereignty and freedom of movement– whether it directly affected them or not. It should not be downplayed that in the process, students were quite literally teaching their Ivy League institutions the greatest moral lesson: You can’t beat a generation of students who view their education as a catalyst for collective enlightenment and a bastion of knowledge. Did Columbia prefer their own students to see it as a path to self-profiting greed and material wealth?

It was directly in this space, on this lawn, that the mantra no man left behind was at the very heartbeat of every interaction. I watched, back in April, as panicked students took down their tents and relocated to the lawn just in front of our Pulitzer Hall building within mere minutes, ahead of an arbitrary deadline set by the President. I watched as they carefully divided themselves into groups to protect those willing to risk arrest and those not. Some were in Keffiyeh’s, others in Kippa’s, some wearing both. I listened as inspiring words were recited that sent chills down my spine: “Our movement is no longer a student movement. It is a mass movement. And we are the generation that says no more.”

The encampments boasted an attention to detail akin to that of a well-orchestrated arena, all crafted and managed by the collective effort of the students involved. Each day commenced with morning assemblies and later art-building activities including large banners and spray paint. Parents, organizers, and restaurant owners from all over, notably Bay Ridge and Patterson, N.J., generously donated trays of Palestinian dishes; salata falahiyeh (farmers salad), warak dawali (stuffed grape leaves), and hummus for all to bask in authentic Palestinian cuisine. Arab music blasted through the speakers, often accompanied with Dabke, the traditional Levantine folk dance. Some children of the organizers who brought food would bike or do cartwheels inside and around the encampment. Students relaxed on the lush grass, some did homework while sipping on iced coffee, others read books from the encampment’s liberation library while nearby, a meticulously stocked medic tent brimmed with essential supplies: first-aid kits, medications, kool aid, masks and more.

On one of the last nights of the first encampment, just as it had started to rain, I watched as strangers gathered inside a tent to dry off. A group of musicians had suddenly formed a makeshift band, beat rhythmically on their instruments, and sang harmonies about how backgrounds were inconsequential to the liberated future they were fighting towards. It was Shirley Caesar’s Black gospel classic “This Joy”: “This little love that I have, the world didn’t give it to me. This little love that I have, the world can’t take it away.” Following an hour-long session of belting out tunes and exchanging smiles, the once-unacquainted individuals now entertained the possibility of becoming a recognized band on campus.

Surrounding me each day were evocative signs posted on the tents, and girdling the perimeter of the encampment, ranging from, “You taught us Edward Said. Now let me use him,” and “People over profit,” to printed poems by Palestinian poets like Mosab Abu Toha who wrote, “What is home? It is my uncle’s prayer rug, where dozens of ants slept on wintry nights, before it was looted and put in a museum,” and the late Refaat Alareer’s “If I Must Die”: “If I must die, you must live to tell my story,” which served as an intimate reminder of why all the students, and those around the world were mobilizing in the first place. Work from Palestinian historians, theologians, novelists, songwriters, and more were on wide display: centered, listened to, and uplifted.

During the morning of the last day of the first encampment, April 30, which culminated with the N.Y.P.D. arrests of over one hundred of our students, a lucid sense of finality hung in the air. The encampment was unusually quiet, devoid of its usually packed agenda; students were cloaked in keffiyehs and face coverings while the first day of grim weather following a week of sunshine mirrored the somber mood.

I spent most of that day perched on flattened floorboards overlooking the encampment, stacked high in anticipation of the upcoming commencement. A teach-in was later held where a woman, whose name will be kept private for anonymity, spoke to the students about safety protocols if arrests were to occur following days of our University President’s emails hinting at an N.Y.P.D incursion.

She asked whether or not students felt afraid. Many responded that they did. The woman then asked the group to give one another a hug. “That is the kind of energy we want to have when we go into these scary moments. We are all we have,” she continues, “Make the choice. Why are you all doing this here today?” An undergraduate student responds: “I’m doing this for my Irish ancestors who I know would be looking down on me proudly,” another says, “I’m doing this for my moral conscience.” It was students, bound to one another by a most radical love, who would save this world, I thought.

As day turned to night, many of the student activists, who had linked in a human chain, stood arm-in-arm outside Hamilton Hall, which they had dubbed Hind’s Hall a day earlier. Their bodies swayed in perfect harmony to the tunes of the African-American protest chant, “We Shall Not be Moved.” Soon enough, the song began to merge with the march of hundreds of police officers who made their way, in formation, toward Hamilton Hall.

Among the human chain, I met the gaze of a fellow student. Although her face was obscured by a hoodie, mask, and keffiyeh, her warm smile, nonetheless, pierced through at me. I did not know her, though, at that moment, it didn’t seem to matter. She stayed smiling, even as officers in riot gear closed in on her and other protestors who were bracing for arrest. I wondered if she felt afraid. Soon after, the police escorted my team and me off campus, kettling many into John Jay Hall. I thought of Palestinian poet and activist Rafeef Ziadah’s infamous words just then:“We teach life, Sir. We Palestinians wake up every morning to teach the rest of the world life, Sir.”

Despite the violent sweep and arrests, Columbia students still returned to reconstruct, redirect and remobilize. The students had made use of a large-scale tent that had been erected by the University days earlier for the reunion weekend. Inside the spacious tent, cooling fans provided relief while tables and chairs were already pre-arranged. A banner was displayed at the forefront to welcome passersby to their joyous reunion with the message: REVOLT FOR RAFAH.

It is these students who have shown that the Palestinian struggle – and their corresponding encampments, was a fight that involved vehemently rejecting the West’s gaslighting and intimidation tactics, and in doing so, freeing humanity from the chains that inhibit our ability to love: Queer students for a free Palestine would paint romantic confessions by queer Palestinians who had been killed over the past year on a large banner in homage to Pride month; a vigil was held to honor the over 40,000 martyrs with poetry recited and wax candles carefully arranged in tribute, and food for all was so generously supplied by the brothers, cousins and sisters of those involved with no question.

Recently, I have been thinking about what it means for Palestinian and Muslim students to seek love from an institution incapable of loving them—of loving anyone more than its’ gentrifying practices, its’ class privilege often camouflaged in multicultural wear, its’ endowments built on others’ suffering, and its commitment to war and insecurity for people who come from my region.

I had long been steeped in doubt over just how attainable the students’ demands were amid a surrounding sea of white supremacy. But watching these self-motivated students, from all walks of life, build truly meaningful friendships centered on liberation and peace, in such a short window of time, has helped me realize that this generation is slowly unlearning, before hastily rebuilding a completely different relationship with time and life, one that does not involve undoing the world, but remaking it as it should be. In this sense, one needn’t have tangible results to see that their wins were far and wide: in the disruption of business-as-usual on all corners of campus life, and in spearheading a revolutionary fight that had already etched itself into the annals of history as the first students, in solidarity with Gaza, who were exposing institutional madness and our problematic status quo for what it really was.

Here was a lifestyle that could only be sustained through a relentless pursuit of caregiving – one that I saw firsthand: “What can I make you for lunch?” a student asks a Palestinian student draped in a keffiyeh walking with crutches. Close by, another student is in tears after a storytelling session deeply touched her, while two strangers embraced her, holding her hand. This was a radical reimagining of a society that promised to include everyone, manifested in every rallying call: Who keeps us safe? We keep us safe.

As every aspect of culture was being deliberately erased back in Gaza, it was the students who were most determined to remind the world that Palestine will never cease to be everywhere. They gathered here time and time again to say they would not leave because, in Gaza, people were cleared out of their homes, hospitals, and universities in dismembered parts. Because in Rafah, babies’ heads were being blown off by American-manufactured weapons, some were buried under mounds of shrapnel and dust in their cribs, while young girls were draped from buildings as though they weren’t once someone’s entire world. Mothers are being forced to recognize their children from the jewelry they wore or the inked names on their forearms. Milestones are being retracted and children are losing legs before they ever learned how to walk. None of it was normal, and here was a safe space for students to agree that none of it had to be; that bedna n’3ayesh (the will to live) will never die.

At around 9 p.m., on June 2, a Jafra organizer commenced a group meeting to express gratitude to all those who showed up over their summer weekend. “Your comradery will not be forgotten. We disrupted business as usual and we will continue to do so, strategically. RevoltForRafah Installation 1 is successful.”

I watched as the voluntary dismantling of the REVOLT FOR RAFAH camp was set in motion. Palestinian singer Mohammed Assaf’s “Alyi El Kofiya” (Raise the Keffiyeh) rang through the speakers as tents, banners, and bed comforters were rolled up and tubs of food were carefully packaged away – all in under half an hour. Far from miserable, the students looked empowered; some danced, took turns singing on the mic, and exchanged hugs and words of encouragement any chance they got. “We’ll be back,” a Palestinian student from the encampment told me, “Giving up is not an option.”

The students appeared nowhere close to surrendering. Because in Gaza, malnutritioned cats with quivering throats continue to keep Palestinians’ company in their final moments on earth, instead of their loved ones. The mesas are raw, still singing their mourning songs for all the martyrs, while the houses are crumbling one after the other, fighting Israel’s thousandth storm.

Gaza is a land of martyrs – those who sacrificed themselves to bring to life something unknown – utopic if you will, though nonetheless still more precious than their own blood, akin to what all freedom fighters, in history, were ever willing to sacrifice. To borrow the words of famed Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, who once said, “Absence is the guide. Absence teaches me its lesson: if it weren’t for the mirage, you wouldn’t have been steadfast.” The encampment is gone for the time being, but the student revolutionaries will continue to remain at the forefront of Gaza’s international resistance. Those who have found a subversive, diplomatic way of being in but not of their universities. Those who have been doing this work not without criticism and self-doubt, but in spite of it. And while much of the world was untroubled by Israel’s catastrophic war crimes for the latter part of the year, our youth were being sustained by none other than the memory of a free Palestine: close enough to touch it, dreams of seizing it, and conspiracies to enact it – one police clash, one jail support, one boycott, and one unionization drive at a time.

Hoda Sherif is an Egyptian / Iranian writer and journalist based in New York. She just received her Master’s from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism.

A Better World Is Possible is an occasional feature of the Amherst Indy that offers snapshots of creative undertakings, community experiments, innovative municipal projects, and excursions of the imagination that suggest possible interventions for the sundry challenges we face in our communities and as a species. This feature complements our occasional column by Boone Shear, who writes Becoming Human.

Have you seen creative approaches to community problems or examples of things that other communities do to make life better for their residents that you think we should be talking about? Send your observations/suggestions to amherstindy@gmail.com. See previous posts here.