Opinion: Against MCAS

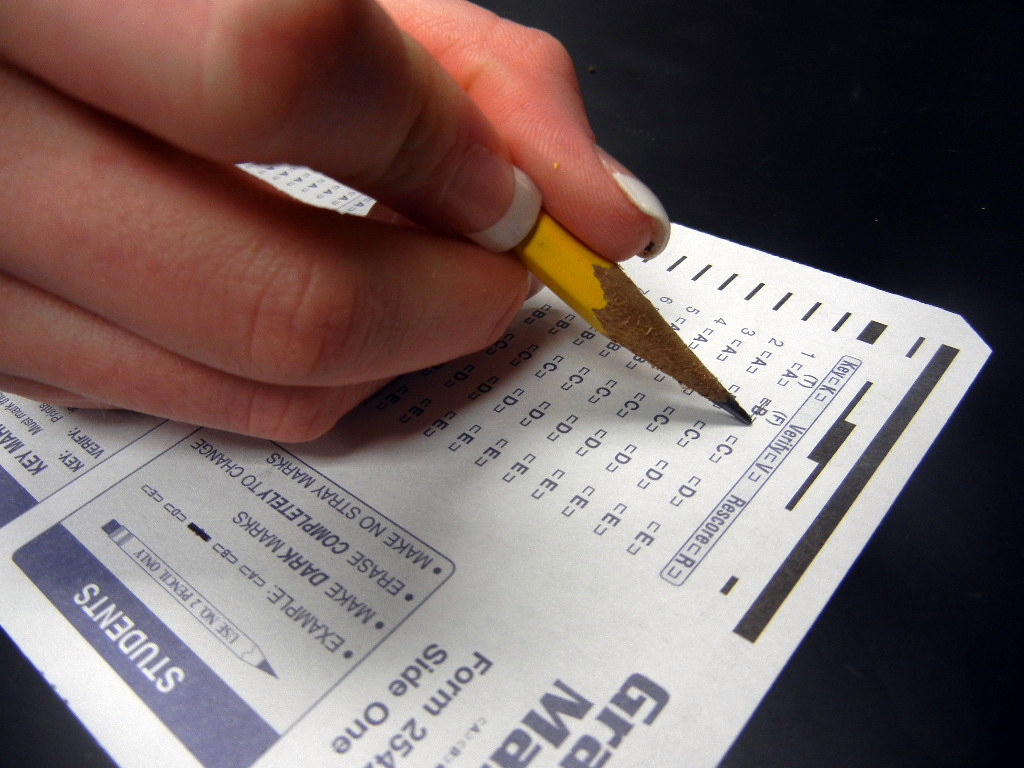

Photo: Flickr.com. (CC BY-NC 2.0)

I am pleased that the Regional School Committee voted so strongly in favor of Question 2 on the November ballot, the question that would remove passing MCAS as a graduation requirement in Massachusetts schools. However, according to the Daily Hampshire Gazette, Massachusetts Teachers Association (MTA) President Max Page assured the Committee that MCAS would remain; only the graduation requirement would be affected if Question 2 passes. I wish he and the MTA and the Department of Education would continue to think deeply about the test and about standardized tests in general.

In 1987 I wrote the following commentary in the Amherst Bulletin. This was before MCAS but after Massachusetts had instituted mandatory testing in elementary and secondary schools. It was during my principalship at Mark’s Meadow Elementary School in North Amherst.

I used to be moderate on the subject of standardized testing. I used to say things like, “They don’t test the important things but they are helpful in the things they do test.” And, “since tests are a basic part of schooling, children should learn test ‘savvy’ early on.” And, “The problem is not with the tests but with their misuse.” And, “Tests can serve a useful diagnostic function.” And, “They do not do much good but they don’t do much harm.”

Nonsense! When I administered the Massachusetts Assessment Test to the third-graders at my school, I finally came to realize why standardized tests are destructive of education. It wasn’t the badness of the test. Nor was it the commonwealth’s naive belief that testing is a path to school improvement. No, not even the tail-wagging-the-dog impact of testing on schooling. No. What saddened me was that not a single third-grader raised a hand to express puzzlement or dismay at items which were so patently confusing, ambiguous, or wrong. I know why they didn’t raise their hands. Because I told them not to. Because I said “Read the instructions and the questions carefully and then do the best you can.” It is my complicity in this mindlessness which has finally nudged me out of my moderation.

Standardized tests are harmful because they are based upon two dangerous assumptions about knowledge: that it consists of right answers and that it is an assemblage of separable items. Now, I do not know whether test-makers actually believe these assumptions but their tests unmistakably and unambiguously assert them to test-takers, and because schools place such weight on standardized tests this version of knowledge becomes the standard version.

What is wrong with the notion that knowledge consists of right answers? After all, most of us believe some version of that assumption and consider it both reasonable and self-evident. The trouble is several-fold.

First, schools teach us to associate success at learning with knowing right answers. Right answers are believed to correspond to the way things really are. A more useful notion of reality allows there to be many ways that things really are and looks for answers which are plausible. Currently accepted right answers are merely the prevailing plausible interpretations. Understanding this leads to flexibility and growth, and encourages people to take responsibility for their own right answers.

The second problem is that knowledge is believed to be an assemblage of right answers, a decomposable assemblage. A more powerful and useful view sees knowledge as the enmeshed elements of a world-picture, and learning as a construction and ongoing revision of world-pictures whose elements are drawn from the widest possible variety of sources. Believing in right answers leads to passivity and uncritical acceptance (and assertion) of authority. Belief in constructed world-pictures leads to active questioning and openness to new ideas. What counts as knowledge depends upon what picture it is in.

Third, believing in knowledge as right answers predisposes us to see the world as decomposable into issues, strategies, decisions, subjects, goals. This prevents us from discovering the deep connections which underlie the loosely-joined surface, which make the world into a vibrant web and ensure that our actions and decisions have both intended and unintended consequences over time and space.

Fourth, right answers persuade us that the world of facts and laws is not of our making but dominates our lives. Not so; facts and laws, like beliefs and values are human constructions. The world may be all that is the case, but what is the case is pretty much up to each of us. So we are not altogether helpless.

Finally, a belief in knowledge as right answers overvalues those disciplines which purport to discover truths and undervalues those disciplines which create meanings, Were the arts rather than the sciences to be the source of our epistemology, standardized tests would be true anomalies; standardization, which epitomizes science, trivializes art.

My 1987 piece goes on a bit and there are some things in the above that I would revise today but the essence stands. MCAS supporters like to talk about standards, but it is really standardization they are talking about. Lurking behind these tests at every level is the infamous bell-shaped curve and the manipulation of raw scores into data points that fit snugly onto that curve. “Grade level” is a myth that derives from the same mythic thinking that assures that 50% of the students will be in the lower half of the class.

I hope voters will follow the lead of the Regional School Committee and vote YES on Question 2. This would be an important first step in restoring our schools as centers of inquiry, learning, success, and adventure.

Michael Greenebaum was Principal of Mark’s Meadow School from 1970 to 1991, and from 1974 taught Organization Studies in the Higher Education Center at the UMass School of Education. He served in Town Meeting from 1992, was on the first Charter Commission in 1993, and served on several town committees including the Town Commercial Relations Committee and the Long Range Planning Committee.