The Cost of Higher Housing Costs

Photo: pixabay.com. Creative Commons

This column appeared previously in the Amherst Current and is reposted here with permission of the author. It may not be reproduced elsewhere without the author’s permission.

In 1984, I bought my house near the middle school for $66,000. It is now worth about $470,000, a sevenfold increase.

This increase in house prices has been great for the net worth of homeowners like me. But I believe it has had negative consequences for Amherst as a community.

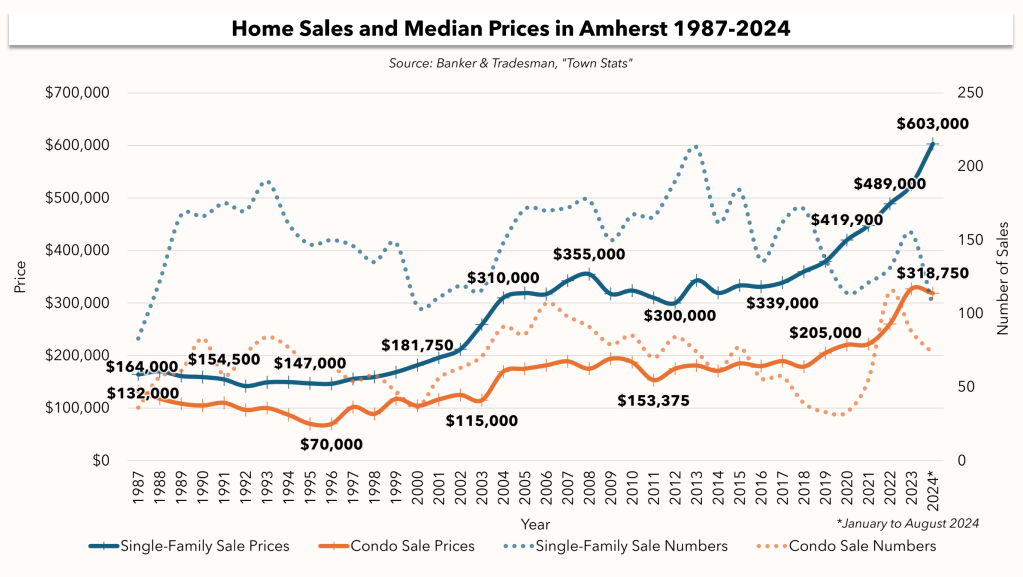

The median sale price of a single-family house this year has been an eye-popping $603,000, compared to $300,000 in 2012, according to the Barrett Group, the consultants hired to address our housing challenges. The median condominium price is now $318,750, way up from $153,375 in 2011.

Rents have gone way up, too. I reviewed the first 35 ads for Amherst rentals on the UMass off-campus housing site and found that they averaged $1,220 per bedroom. A studio apartment at One East Pleasant goes for $1,930 a month.

Here are some problems that this inflation in housing costs has created:

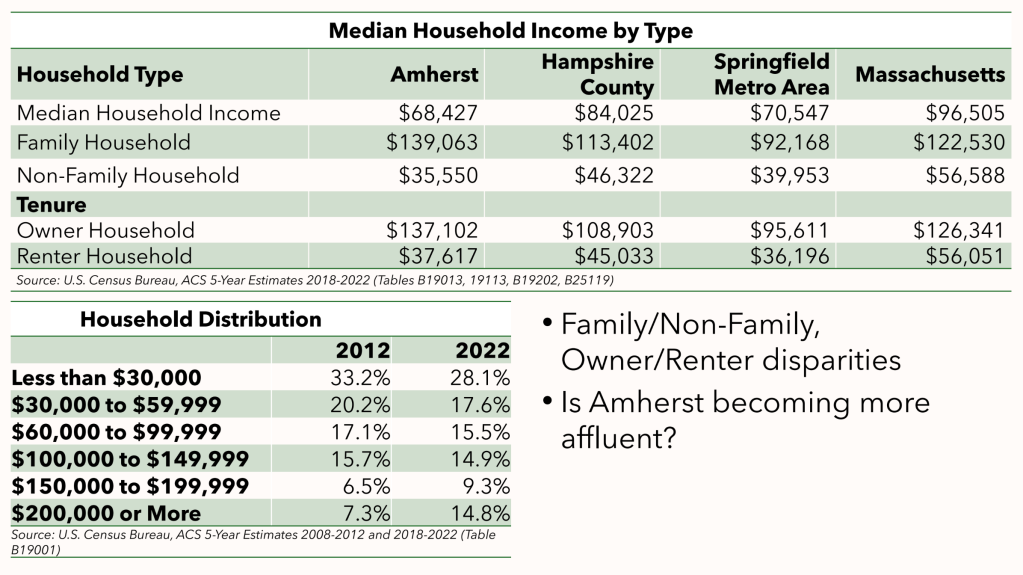

The rich get richer… Homeowners, who are more likely to be white and well off, are accumulating wealth, while renters, who are more likely to be students and/or people of color, are paying higher rents without building equity. The average annual income for homeowners in Amherst is $137,102, while for renters it’s $37,617, a much wider disparity than in Massachusetts as a whole, according to the consultants.

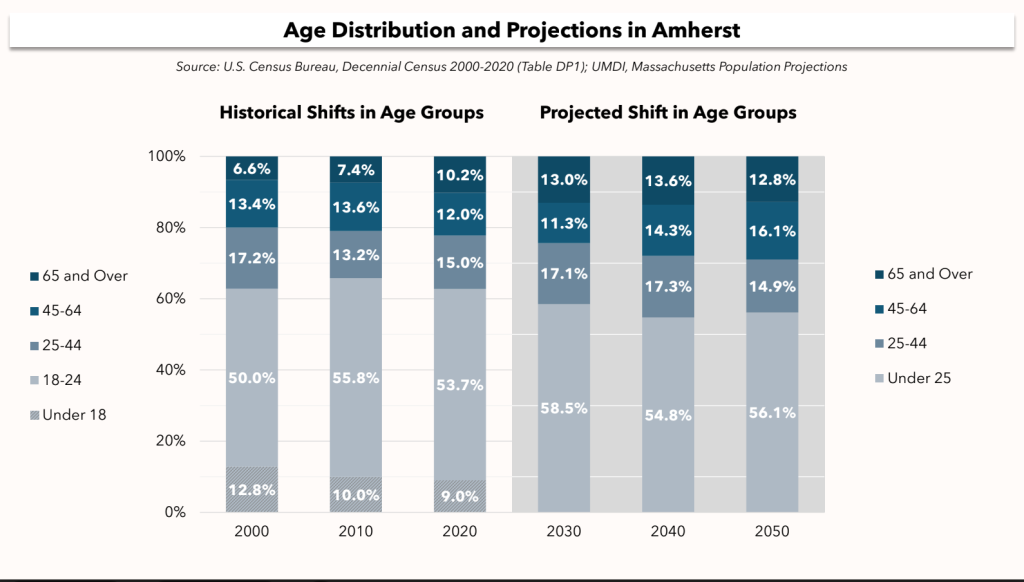

Young families are shut out. It has become very difficult for young couples to afford a single-family house in Amherst. While the over-65 Amherst population has grown from 6.6 percent in 2000 to 10.2 percent in 2020, the number of students in the public schools has dropped by 40 percent (from 3,648 to 2,193), according to the consultants. Charter schools and demographic trends have also contributed to the enrollment decline.

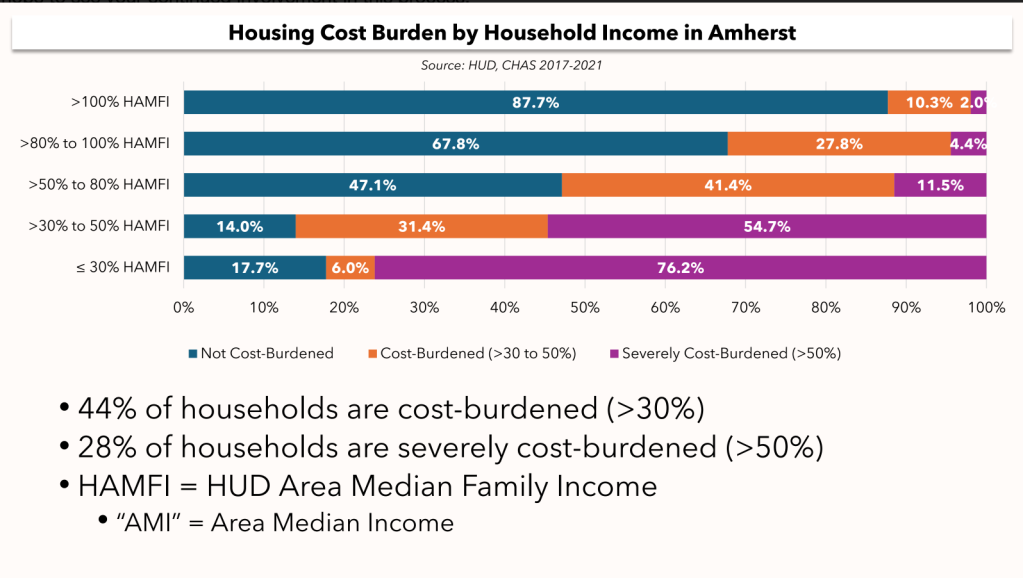

Struggling students and service employees. Twenty-eight percent of the households in Amherst are “severely cost-burdened,” meaning they spend more than 50 percent of their incomes on rent, according to the consultants. Some UMass students, unable to find housing in Amherst they can afford, have looked for apartments in Easthampton or Springfield. Wait staff and retail workers often have long commutes and/or crowded living spaces.

Social stratification. It becomes more difficult for Amherst to see itself as a unified community when the gap between homeowners and renters is wide and widening. While the Survival Center has met a much greater need for free food, Amherst households with annual incomes over $150,000 are now 24.1 percent of the population, up from 13.8 percent in 2012, according to the consultants.

Budget pressure. It has become more challenging for people who work at Town Hall or the public schools to afford a place to live in Amherst. So it’s not surprising when their unions advocate for pay increases. When they are granted, it becomes more difficult to keep the town’s budget within its limits and to avoid asking residents to raise their already-high taxes.

These problems are not new. “There is an overwhelming consensus among those living, working and wanting to live in Amherst that there is a critical need for increasing access to affordable housing, both for rentals and home ownership,” according to a summary of a listening session held last year.

Housing expert Connie Kruger addressed the price gap, the “missing middle,” and a housing proposal before the Town Council in this Amherst Current post. She reported here about the new state law prohibiting towns, including Amherst, from requiring owner occupancy for Accessory Dwelling Units. State action may be necessary to overcome local governments’ resistance to zoning changes designed to make housing more attainable.

The Barrett Group has been conducting interviews about housing, and they plan to do an online survey this month. The consultants will organize focus groups on “implementation strategies” in January, and are due to provide a final “housing production plan” in April, when the public can review it.

What the market dictates for developers and what’s actually needed are not the same, said consultant Judi Barrett. “There are too many needs competing for the same inadequate supply,” she said at a public presentation Oct. 1.

These higher prices are probably the new normal. Like property taxes, house prices seldom go down. Even in the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008, when average U.S. house prices declined by over 20 percent, in Amherst they held steady.

Barrett outlined some changes since the housing plan was updated in 2013: Amherst has more higher-end apartments, more investors are buying houses and converting them to student rentals, more students are living off campus, and young families and the work force face increased housing challenges. UMass has 4,213 more students than it did in 2010.

Meanwhile, construction costs have soared in the past five years, making it extremely difficult to build affordable housing without governmental subsidies.

Because Amherst has little available land that’s suitable for development, the most commonly voiced response to housing scarcity is increased density. But neighbors often resist, and have gotten good at resisting, said former Select Board Chair Elisa Campbell at the October 1 meeting. Former Town Meeting Moderator Francesca Maltese articulated a key question: “How dense can we allow Amherst to be and still be a nice town?”

Amherst has been making some progress lately, with plans for lower-cost housing at the former East Street School, the former VFW building on Main Street, and on Ball Lane in North Amherst.

The Affordable Housing Trust drafted an ambitious “action plan” in September. It included the creation of 200 homes, for rent or ownership, over the next five years. The draft plan proposed finding $4 million to support this effort, perhaps through a 3% “community impact fee” on short-term rentals, a real estate transfer fee, and a contribution from the Community Preservation Act fund.

Amherst is not likely to abolish single-family zoning to increase density and affordability, as Minneapolis did. But many other strategies were voiced at last year’s listening session, all with pluses and minuses. They included subsidized rents, getting UMass to build more on-campus housing, rent control, tiny houses, disincentives for turning homes into student rentals, a tax on college meals, and banning Airbnbs. Here’s a link to more details.

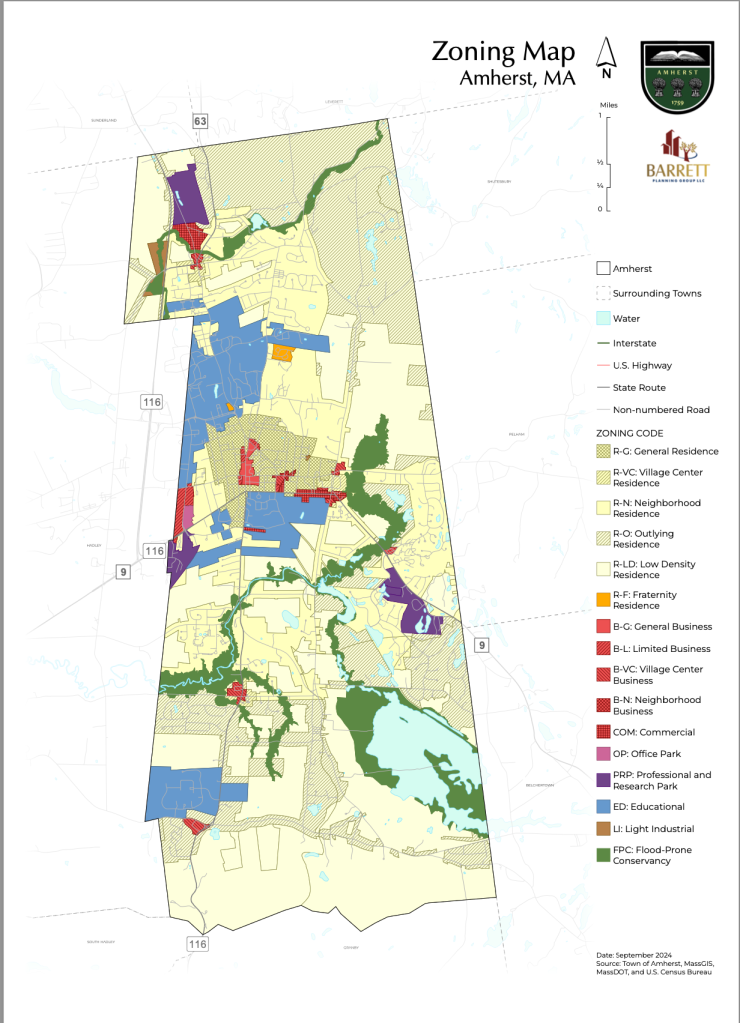

Amherst’s zoning map shows districts that are known by acronyms, such as RG (General Residence) and BL (Limited Business), each with their own development rules. A frustrated wag once said that Amherst should create a new zoning district where all kinds of development would be allowed. It would be called SEN, which stands for Someone Else’s Neighborhood.

It’s easy to say that Amherst needs the build more housing. But it can be hard to convince residents to support changes that would allow that to happen.

Nick Grabbe is a co-founder of The Amherst Current. He has been a resident of Amherst for nearly 40 years and served as writer and editor for the Amherst Bulletin and the Daily Hampshire Gazette 1980-2013.

I bought my first building lot in Amherst Woods for $17,500 in 1981. It was the only lot that Jeff Flower sold that year.

I bought my last lot in 2008 for $175,000 having built over 50 homes in that time, it was a great place to do business.

Build out happens, …build up is the solution.