An Introduction to the History of Housing in New England

House framing, 19th century. Photo: detail from jeanhuets.com/whitman-house

Amherst History Month by Month

This is the first column in a five-part series.

Housing and our homes are basic to our existence. This is a topic that most people have opinions about. Here are a couple of cold, hard facts: today, nationwide the median homebuyer is over 15 years older than the same person in 2000. This past fall, the median sale price this year of a single-family home in Amherst was around $603,000. The town-wide median value of single-family homes in Amherst is $464,000). Homeownership has moved out of reach for most young Americans. Even renting a home or an apartment can be very expensive in Amherst.

Writing about historic preservation here in the Indy has meant that I have contributed a couple of articles about housing. Then, a year ago, I wrote about where I thought we were in terms of preservation issues locally and posed this question: “Has investing in historic preservation principles helped Amherst embrace a variety of housing choices for people wanting to move here? Are we making sure that any new structure is compatible with our existing built environment, and that development has some degree of environmental sensitivity?” Coinciding with the preservation and sustainability aspects, the reality of a lack of affordable housing in town creates its own pressure cooker. It also makes for a tricky environment in which to deliberate – as I must do as a member of the town’s Historic Commission – on demolition delays due to the perceived crisis level of need. While trying to save local historic buildings of architectural significance, there has occasionally been the unspoken argument made in public hearings that ‘surely you can…’ grant demolition requests due to space being needed for housing.

This past October, our town engaged the Barrett Planning Group to conduct demographic, housing, and market research hoping to involve residents and others in developing a new plan that might “identify housing types needed in Amherst; and consider various approaches to secure affordable housing for all residents.” It got me thinking again, partly in an historical context and partly in contemporary terms about the topic. Social housing was a special study of my graduate work in architectural history, and the history of housing policy has helped shape our current situation.

Designing homes and housing is a part of architectural design, and architecture is a supremely social art form. Like other forms of building, housing is experienced in three-dimensions, and this makes it a compelling element when assessing how well we live and thrive. Why has housing never been treated as part of our public infrastructure like our roads and bridges or our sanitation? And why hasn’t it been considered on a par with education by which I mean public education? It is usually acknowledged that, historically at least, Massachusetts led the way in that policy area. While I don’t have enough of a background in history of social housing in New England, it seems that, instead of affordable and well-designed housing, what we often get is housing that is neither aimed at most of the workforce nor is affordable. Instead, it is a market commodity. Locally we are experiencing this acutely where we can see more rented/leased space dedicated to college-age residents who are typically in town only for eight months of the year rather than than other segments of our population. There are many architects, politicians, builders, planners, tenants, community organizers, social workers and developers – indeed, the entire community of stakeholders – who agree that housing is a pressing need including those citing the price gap of the “missing middle.”

The prevailing highly individualistic culture that we all inhabit and sometimes help to shape doesn’t make owning or renting a home feel like something most of us can achieve. And yet home ownership is held out as a (leftover Puritan?) virtue. We’re raised to adulthood with the aspiration to help grow a home-owning democratic culture as well as to create personal assets and/or amass wealth. The economic and social benefits of being a homeowner even seem proof of a life more honorably lived somehow even if this is due – not to individual effort or beneficent providence – but to the benefits of class, gender, or race.

Public funding for housing has historically been a kind of football passed between all political parties. Most stakeholders appear to be determined to not mess much with the profit motive. Its forces have won out over the need for a national housing policy going back to the 1930s and the era of the Great Depression. Whatever way you decide to characterize the factors, conditions, or explanations for the current state of our housing, it tends to fall far short for many struggling for a foothold into the American dream. About 28% of Amherst’s families and individuals struggle with housing costs (more if you include most of our students) and it is in part because we have both a local and a national housing shortage. (Editor’s note: the recent in the recent Amherst Housing Production Plan survey, 58% of respondents said they have experienced a housing cost burden at least once in the past year and 39% said they are consistently cost-burdened every month.) Adding to the issue is that demands on most of us, economically, tend to pit rent against medical costs, or childcare costs against mortgage payments or all the above over the costs of food: all that juggling makes the dream less attainable.

Lev Ben Ezra, the Executive Director of the Amherst Survival Center (ASC), shared this story in the November 2024 ASC newsletter: “A couple of weeks ago, a young dad was pushing his cart full of groceries, adorable kiddo hanging off the front. She was gripping the cart, and a coloring page she had drawn while waiting for their turn in the [food] pantry. “You find everything you needed?” I asked as I held the door open. He paused, nodded, and said simply – “I found rent.” For him, these free groceries meant he could make rent that was due a few days before.”

A further contextual factor contributing to our housing woes are the very high costs of purchasing land and building materials. Unsubsidized home construction is also very expensive.

Housing in New England History

The ‘local history’ dimension of this topic is interesting, especially when trying to track modest housing and homes for the many rather than stand-alone mansions for the few. The story begins with the beginnings of the Republic itself. As our country began to take shape – lagging immediately in terms of equities of race, gender, and class – towns and cities in the Northeast began to grow and to experience population change. The process happened unevenly in the emerging and newly industrializing nation. New kinds of housing emerged that dramatically recast the landscape of New England, especially in the 1790s and early to mid-1800s. I will introduce this history here and talk more about it in subsequent articles.

One thing is clear: we need a process of “reparative description” to better understand New England’s housing history. This is because securing a home has been harder to come by for many groups in our country. African Americans, all indigenous groups, and in fact all our communities of color, have found the search for housing much harder than have other segments of the U.S. population to date.

As an example, for much of the 19th century, and specifically, after the Indian Removal Act of 1830, indigenous peoples in New England and nationwide were often preoccupied with what had happened to their treaties in times of war. Indian real estate interests had been whittled away or lands had been ceded in transfers of ownership modeled on non-native legal terminology. Tribes were trying, in particular, to hold on to their historic burial grounds, or they were beginning to experience the terrible impact of forced migration. Later came the violence of being moved into boarding schools and onto reservations. This made it impossible to build up equity in a home.

In New England, workers’ housing created by individual industrialists or small corporations operating philanthropically began to be built in the early 1800s. The form this took was in the design of row houses or congregate housing such as the homes built for workers in the Massachusetts mill town of Lowell, just north of Boston.

Closer to Amherst, in Winchester, New Hampshire in the 1820s, the Ashuelot Manufacturing Company Mill likewise created a boarding house for its workers. By 1868, when they added a second building, the mill overseers could house as many as 50 immigrants at a time who had come to Winchester from Quebec, Poland, Ireland and other countries to work in the adjacent woolen mill. (Read more about this site at the New Hampshire Preservation Coalition’s website. The boarding house was bought in 2020 by a town resident who was concerned about its future and the plan is to rehabilitate the building for use as a creative arts center that includes letterpress printing classes.)

Coinciding with new building types were some crucial technical innovations in the construction industry: the invention of balloon-framing techniques from around 1830-32 helped to streamline construction of multiple-unit buildings for a village or town setting. Standardization came slowly but did eventually make the provisioning of smaller, new homes more possible.

Many workers in the boom years of industrializing New England were often housed as tenants or boarders in the homes of people who either had room or needed additional income themselves. Social housing was different from housing bought, managed or built as a “benefit” tied to employment at a mill or factory. Some factory and mill owners built “fit-for-purpose” housing for their workers.

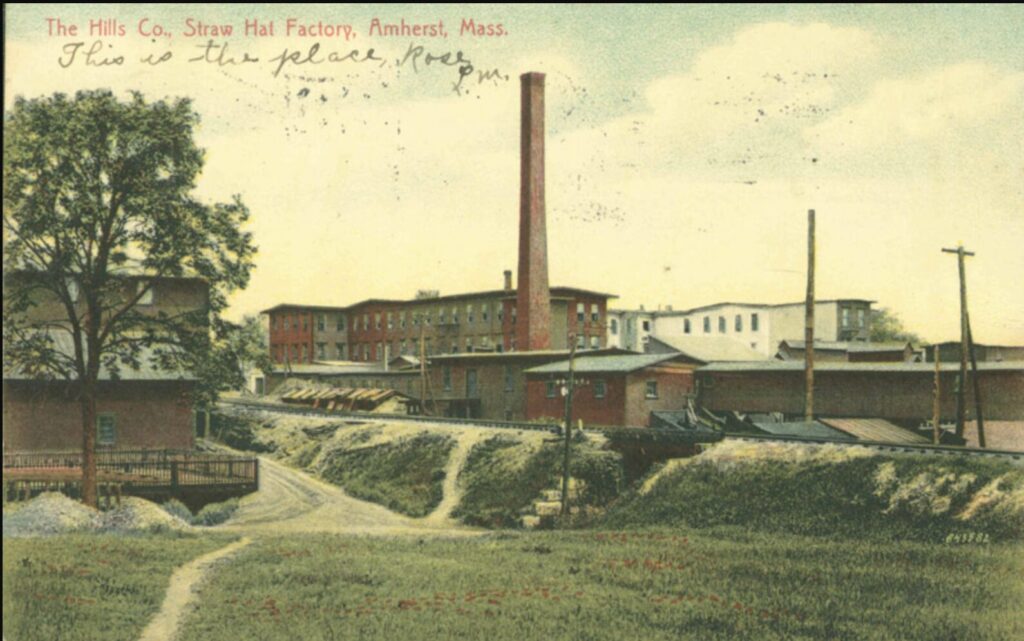

Coming closer to home, here in Amherst, the story about affordable housing takes a different tack. From the 1830s onwards, one of the most important manufacturing businesses in Amherst did not offer purpose-built worker housing. This was at the LM Hills palm leaf hat making factory that had been started in 1829 by Leonard Mariner Hills (1803-1872) The lack of on site housing was because the work was based initially on the cottage system, where a mostly female workforce constructed the hats at their homes. They would then bring them to the factory (located first in East Amherst and subsequently at the site on the corner of College and Railroad Streets) for finishing. There was even an LM Hills factory in North Amherst. As the company grew, the process began to change over time. This was due in part to the factory being rebuilt following flooding in the 1860’s and the shift from “piecemeal” production to hats and “Shaker hoods” being completely made in the newly built factory on Railroad Street. Some parts of the business operation were also located in New York City. Even after the initial buildings were swept away in floods in the 1860’s and were rebuilt, purpose-built housing for employees was not considered. But it did exist in North Amherst in 1832 where there was a cotton mill located in Factory Hollow that provided boarding house accommodation. We know this because its company account books indicate payments for the boarding of workers. It appears to have been the case at the LM Hills factory in North Amherst in the 1850’s as well. (More about the history of North Amherst’s mills and the “Dirty Hands District” will be told with the construction of the Mill River History Trail. “

Here are two historic examples that are not listed as historically or architecturally significant but that survive as examples of mid-to-late 19th century affordable housing that were possibly planned with workforce housing in mind. While the Buckland/Shelburne Falls example may have been constructed to offer nearby rented housing for people working at the grain store (now the Salmon Falls Marketplace, at #1 Ashfield Street), the Northampton example may have provided housing for workers at the nearby Belding Silk Mill on Hawley Street.

Mill owners continued to house workers who they employed in existing housing stock: here, some of these mill workers were boarders, paying rent to their employers via their wages. Overcrowding could be an issue; in a house owned by a cotton mill in Olneyville, Providence, RI for example, eight people of Polish heritage lived in three small rooms, where three were boarders. Rent was $4.50 a month.

That renting could be a hardship for people of modest means sometimes necessitated a ’moonlit flit” that meant being evicted. It was considered the plight of the poor at the time. To stem such hardships, the provision and construction of congregate housing or other homes financed from private sources was a crucial contribution to housing stock.

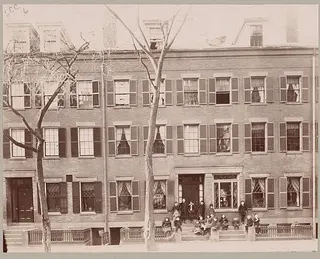

Individual humanitarians or agencies like settlement house founders or religious groups were also important provisioners of housing. Two examples might be St. Joseph’s Home for Working Girls in Worcester, MA – originally a boarding house for working women – and Dennison House settlement, founded in 1892, in Boston. The founders of the settlement house took an existing townhouse on Tyler St in the South Cove and over time expanded it to four connected dwellings.

“Closely associated with Wellesley College…Denison House was one of three settlements established by the College Settlement Association, founded in 1890 with the mission to “bring all college women within the scope of a common purpose and a common work.” As part of their work in largely immigrant neighborhoods, these more privileged white women found independence, their life’s purpose (famously like Jane Addams) and a place to live. Purpose-built housing could also be built in several different architectural styles popular in the mid-to-late 1800s and early 1900s.

So the provision of adequate housing for the general population comes late to our country and in the interim, is a need that is met in all sorts of informal, voluntary ways. New architectural designs for multiple housing emerge but it is not until the 1930s that a national housing policy really comes into being. In the next four articles, I will explore further more recent histories of housing in our part of the state, and also endeavour to come up closer to the present time.

This article along with the photos is amazing. A big thank you to the author for the work involved, and to Amherst Indy for bringing it to us!

Thank you, Inge. That means a lot.

And a recent follow up to the subject of burial grounds and more recent history, seen in this article: https://ccrjustice.org/home/what-we-do/our-cases/sacred-ground-fight-protect-burial-sites-enslaved-people?emci=d2eb58b1-8c5e-f011-8dc9-6045bdfe8e9c&emdi=bb00cac7-e460-f011-8dc9-6045bdfe8e9c&ceid=24604121