Introduction to the History of Housing in New England, Part 2: Early Privately Funded Housing Developments

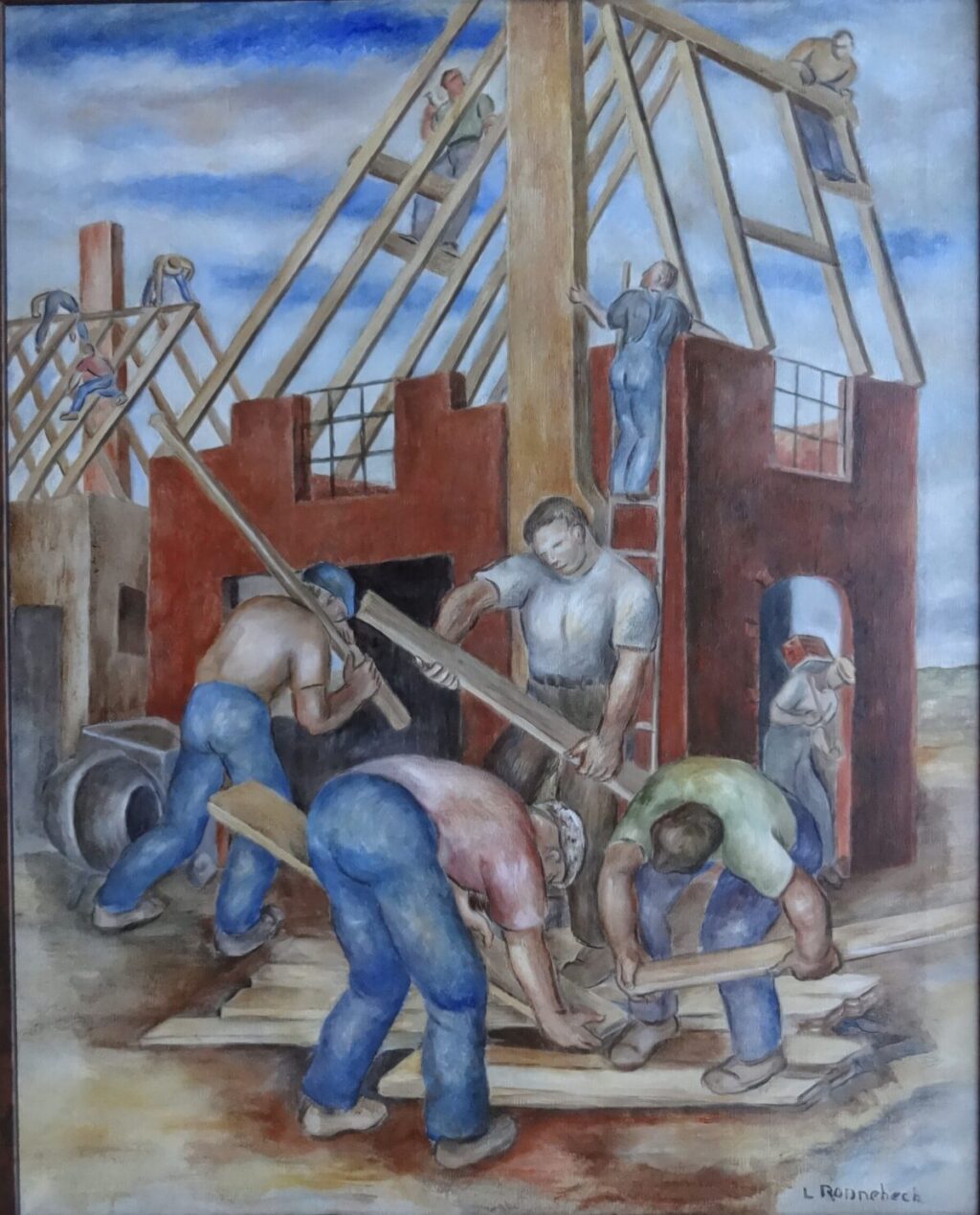

Building Boom, Louise Emerson Ronnebeck (1937). Oil on canvass.

Amherst History Month by Month

This is the second in a series of five articles. Read Part 1 here.

Two of the principal ways in which public housing was funded in New England in the mid-to late 19th century were through charitable organizations and private patronage. It is possible to argue that the only kinds of public supported housing for New Englanders to emerge at mid-century were the kinds of homes that came with employment, such as in military service or on a farm, or plantation. Some mill and factory employment also came with housing that might be purpose-built. There were other kinds of options like being a “winter Shaker” (living part of the year in a Shaker village and part of the year as an itinerant laborer). This mixture of offerings extended until the end of the 1800s.

I want to mention a couple of examples that are closer to Amherst to try and pull the story into our geographic orbit. In 1883, a small group of women in nearby Holyoke, calling themselves the “Rain or Shine Club,” wanted to amplify options for permanent and stable housing for elders in their community. In 1902 they secured a charter and two acres of land donated by local philanthropist William Stiles Loomis. They hired architect James Clough to create a spacious Queen Anne Revival style building that opened in 1911. Each unit or apartment was for men or women and, seen collectively, appeared to be a part of a larger mansion that was known as the Holyoke Home for Aged People.

Loomis homes still exist today and more clearly honor their benefactor; the Loomis House-Holyoke and Loomis House-South Hadley developments were mentioned in my recent article about South Hadley.

On the other side of the Connecticut River Valley, in North Adams, a similarly funded series of row houses was built between 1899 and1901 that owed its existence to a couple by the name of Walter and Susan Boardman Penniman. They had made their fortune in manufacturing metal hardware and were also local developers. The row houses occupied an entire city block on Montana Street and the architect, Edwin Thayer Barlow, used both stone and brick in his design. Known as the Boardman Rowhouses (see also here) they are Colonial Revival in terms of their architectural style. They had rooms for servants on the third floor, and were planned for much-needed middle and upper-middle class housing. The Pennimans themselves once lived here. The homes today are located across from the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts.

buildingsofnewengland.com

Another kind of privately funded housing type to emerge in the late 1800s was the “triple decker.” This was a significant contribution to New England’s social housing, as it offered a different path to asset building and housing security for working individuals and families.

Triple deckers can be found today in cities like Dorchester, Worcester (where the house type is thought to have originated in the 1880s), and Woonsocket and Providence in Rhode Island. There are also triple-deckers closer to home in places like Turners Falls, north of Amherst.

As they are actively being preserved as examples of sustainable housing stock, triple deckers may even be making a comeback as a model for future housing trends.

Housing Reform in the Progressive Era

Policy relating to perceived housing needs as well as development opportunities changed with a new generation of urban reformers who began to play an increasing role in local and national government in the Progressive era, dating between 1901 and 1929, the start of the Great Depression. Progressives demanded health and welfare services related to emerging housing policy and also addressed issues such as immigration, health and safety in the home, infant welfare, and public sanitation. Voters up and down the ticket swept out the influences of the robber barons and ushered in a new era. This political shift also made it possible for larger insurance companies to own their own housing developments. Cities and larger towns also began to act as the patrons of what would become public or social housing, which were somewhat prestigious by the 1920s, when homes “fit for heroes” were constructed for American soldiers who had served in World War 1. However, with this impactful new level of provision came something much less humane: an era of racially restricted housing covenants that made it almost impossible for African Americans to purchase or rent a home in many places in this country, including New England, in the period between the two world wars of the 20th century.

Construction of triple deckers dwindled after about 1920, although triple deckers continued to make it possible for immigrants to own and at the same time draw income from their own homes. Most triple deckers were divided into three apartments, although some were made into six apartments if they were deep and wide enough. Here is Al Pacino talking about his childhood apartment in a piece he wrote last year for The New Yorker:

“My mother’s parents lived in a six-story tenement on Bryant Avenue [in New York City] in a three-room apartment on the top floor, where the rents were cheapest. Sometimes we would have as many as six or seven people living there at once. I slept between my grandparents or in a daybed in the living room, where I never knew who might end up camped out next to me – a relative passing through town, maybe my mother’s brother, back from his…stint in the war.”

During the Great Depression in the 1930s, regional city planners advocated for more affordable housing units and fewer obstacles for people wanting to rent or own their own home. Planned towns emerged, such as Radburn, New Jersey, which was “a garden city for the motor age” funded by the City Housing Corporation in 1928 that incorporated modern design principles and was designed by Clarence Stein, Henry Wright and Catherine Bauer.

Radburn is in Bergen County, across the Hudson River from New York City and a little to the north. It is worth noting that Bauer’s role was “hidden from history” until the last few decades, when she was finally credited as a designer of the scheme on a par with her colleagues Stein and Wright. The plan for Radburn introduced the “super-block” concept along with the protected, interior park-like spaces in some social housing developments. Radburn and other “Garden City” type housing schemes (such as Sunnyside, New York) increasingly tried to separate automobile and pedestrianized traffic.

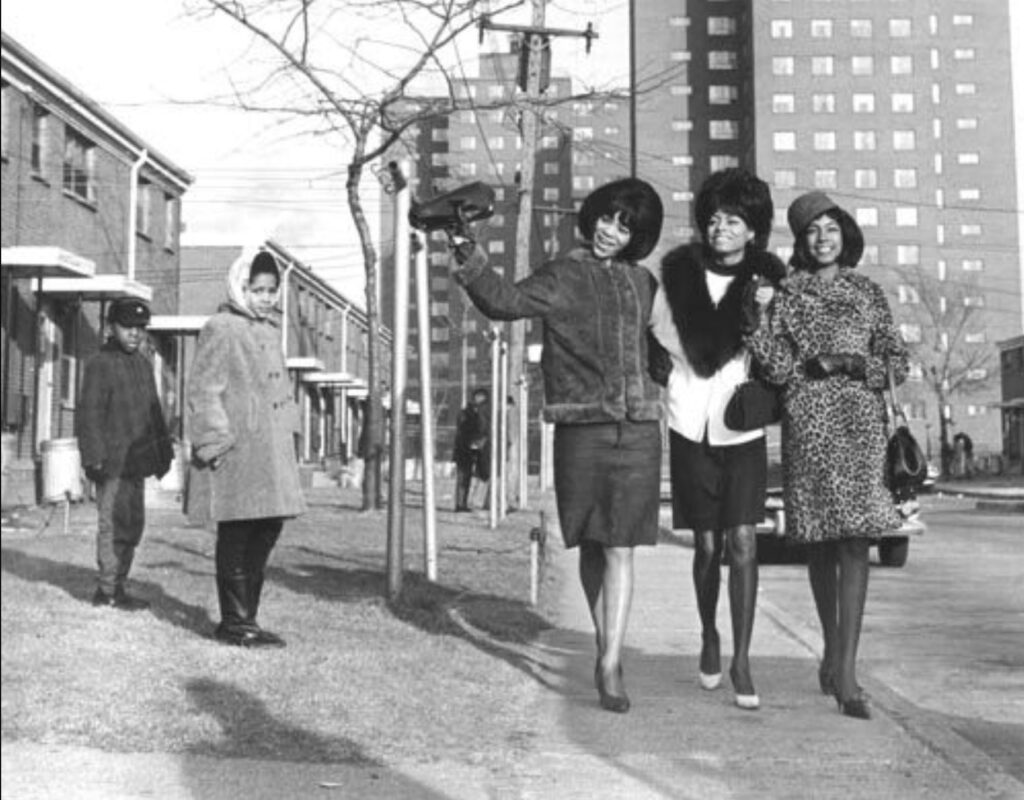

It is only [just] within living memory (the mid-to-late 1930s) that the “greatest nation on earth” set up federally supported policies for housing in part due to the efforts of Eleanor and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The 1934 National Housing Act created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) that helped to provide mortgage insurance on loans made by FHA-approved lenders. But while there were finally Federal home loans available, racist red lining practices continued. A first of sorts, beyond New England, was the construction in 1935 of Brewster Homes, in Detroit, Michigan, the nation’s first federally funded public housing complex aimed at African Americans. The project was promoted by Eleanor Roosevelt and opened in 1938 with 701 units. Two members of the Motown group the Supremes lived here at one point.”

Progress in terms of public funding for homes and other types of housing continued throughout the 1930s. September 1937 saw the passing of the Wagner-Steagall Act and the creation of the U.S. Housing Authority (USHA), which offered $500 million in loans for the construction 0f low-cost, modest homes. Catherine Bauer was the primary author of the act and was named Director of Information and Research at the USHA. National Housing Act Amendments in 1938 provided a secondary market for FHA-backed loans and this turned out to be a much-needed financing refinement that came about apparently because the private housing sector didn’t create mortgage associations to buy FHA mortgages as had been planned.

The third part in this series will address the post World War II period in terms of both housing policy and share examples of the architectural styles associated with a period of more intentional national housing provision.

Readers of this Feature may be interested in this housing scheme, shared by the New York Landmarks Conservancy as part of #BlackHistoryMonth called Harlem River Houses. These homes are located on West 151st to West 153rd Streets, Macombs Place to Harlem River Drive, Manhattan, NY.

“One of the first federally-funded housing projects in New York City, the Harlem River Houses were built in 1936-37 to the designs of a team led by architect Archibald Manning Brown. The project aimed to provide quality housing for working-class African Americans. The 4-5 story buildings are set on a landscaped nine-acre site. The human scale, generous open space, and handsome detailing set a standard for public housing that has rarely been matched. Among the architects was John Louis Wilson, Jr., one of the early African American architects registered in New York State. The complex was designated a New York City Landmark in 1975 and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. More info here https://savingplaces.org/stories/the-experimental-history-behind-the-harlem-river-houses