The History of Housing in New England Part 3: A Federal Mandate

Squatter's shacks in Central Park, New York City, during the Great Depression, with the landmark Dakota Apartment building in the background. The Hooverville grew up at a construction site where work was suspended. Photo: Shutterstock

World War II and the Housing Boom from Mid-20th Century Onwards.

Amherst History Month by Month

This is the third in a series of five articles. Read Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

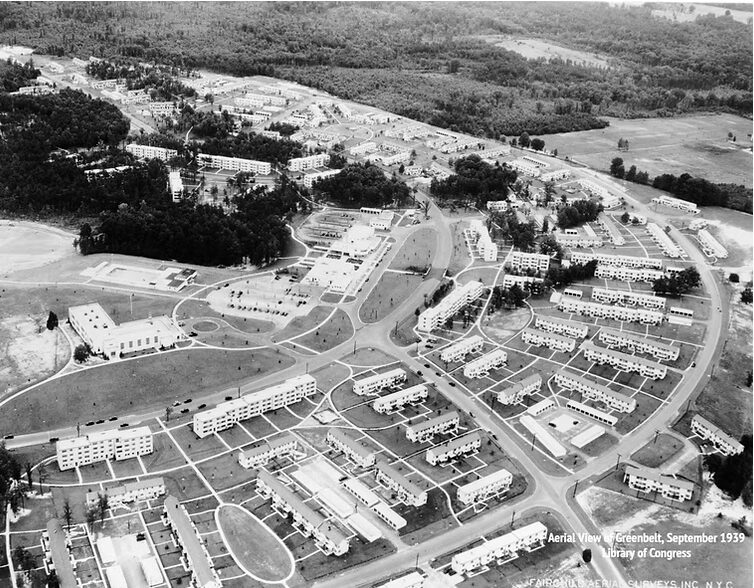

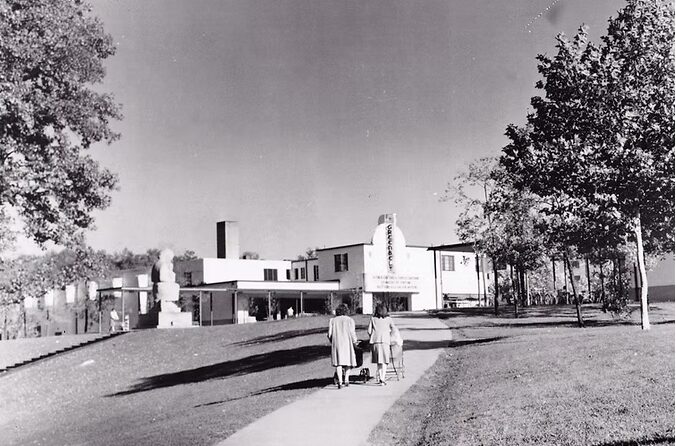

With the passing of ground-breaking legislation for public housing by the late 1930s, the federal government began to create social housing to equal that already existing in other developed or developing countries, world-wide. One project worth mentioning were three new towns, of which Greenbelt, Maryland (1937) is the most well-known.

They were all-white towns (the two others were in Ohio and Wisconsin) and were designed using the architectural styles known as Art Deco and Streamlined Moderne, seen in public architecture projects of the New Deal era. At the same time, President Franklin Roosevelt was also ramping up for war behind the scenes with various kinds of procurement and this included funding for construction for housing on U.S. army bases for enlisted soldiers and their families in places like Fort Devens, MA. The new world war had its own momentum, assisting in re-fueling the economy after the Great Depression.

Closer to Amherst, cities like Springfield, a “City of Firsts”, also known as the “City of Homes”, began to think far beyond its now well-established 1800s-era neighborhoods of Victorian revival-style houses. City officials realized that they needed to make provision for newer homes for workers and their families employed at places like the Springfield Armory and the Smith and Wesson manufacturing plants. When Smith & Wesson relocated its headquarters to East Springfield, joining companies like Westinghouse, Springfield ramped up production for the war effort by funding a housing complex in 1942 under the United States Housing Authority.

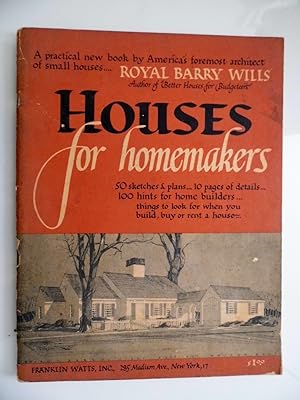

The architect chosen for the new Springfield housing complex was Royal Barry Wills (1895-1962) (see also here) who was born in Melrose, MA. He graduated from MIT in 1918. From 1919-1925 he worked with a design engineer at Turner Construction Company and opened his own office after that. In his lifetime he was as well-known as Frank Lloyd Wright.

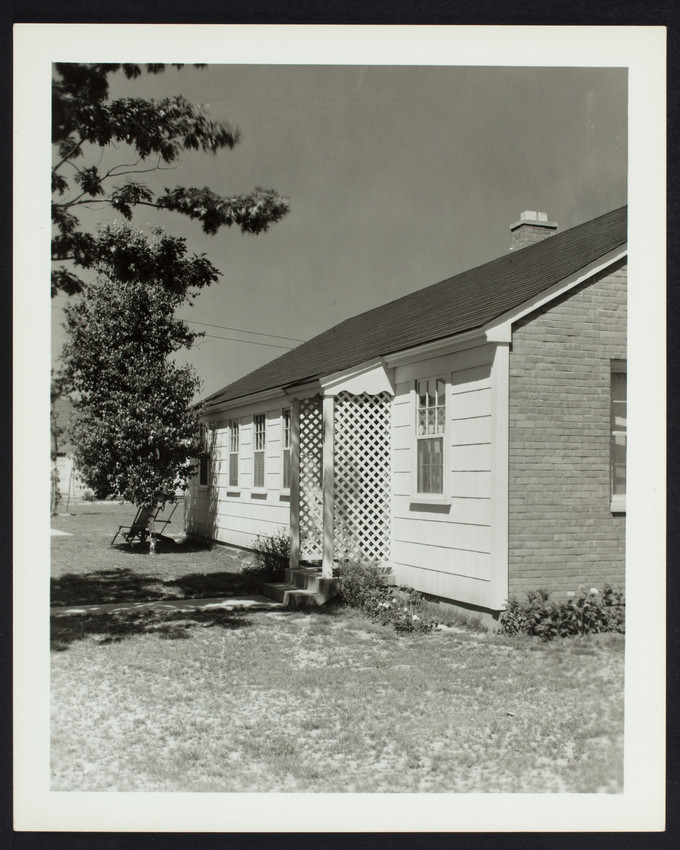

Wills’ homes in Springfield were designed for two to four families rather than as single-family homes. Three hundred units were completed by the end of the war in 1945. Officials named the project after “Mother Mallory” (Lucy Walker Mallory) a philanthropist and local missionary who had worked in Springfield with immigrant families. Many of the residents worked at the Westinghouse plant.

Lucy Mallory Village is located on St. James Avenue and the housing re-created the original 1700s Colonial era homes of the Pioneer Valley. Will’s career to that date had mostly been defined by domestic architecture commissions, and he had sought recognition for his ideas about home design by entering design competitions for housing. In 1932, he had won a gold medal from President Hoover for the National Better Homes Competition. He mostly designed for private clients in the eastern part of Massachusetts and in New Hampshire, but in 1937 Wills designed a home for George Davis on Bernardston Road in Greenfield, known as the Davis-Cohn House. George Davis was Vice-President of the Greenfield business and manufacturing firm, Lunt Silversmiths. The owners before the current ones (who allowed me to take a few photographs) were Simon and Arlene Cohn. Mr. Cohn worked for the Cohn Real Estate Company, the largest business of its kind in Franklin County. This well-preserved home is a lesson in understated elegance, set back on its lot with a rolling front lawn. But Wills had also made his designs accessible in multiple books, sustaining a lively and popular secondary market for his ideas that attempted to be more accessible than commissioning any of his single-family homes. A very good copy of one of Will’s so-called Cape Cod style houses was built in Amherst on Elm Street, in 1948, a home I had thought was actually designed by Royal Barry Wills.

Some readers here may think this a little out in left field, but the Lucy Mallory homes might be compared stylistically to the then-new Friendly’s restaurants, founded by Curtis and Prestly Blake, that appeared in Springfield after 1935. Their company headquarters in Wilbraham, MA looks a little bit like a stately James River mansion or pretend Palladian villa, while the ice-cream restaurants themselves that eventually dotted the east coast were also Neo-Classical in feel but cozier, smaller in scale, and “friendly.” Many of the earliest examples of the roadside restaurants had quoins, the corner blocks that were suggestive of structural masonry in larger colonial homes from the 1700s. Their style was instantly recognizable – perhaps like the orange roofs and golden arches of their competitors – and coincided with the motor-age.

A different trend in post war housing in terms of architectural design stems from the legacy of the ‘garden city’ model first demonstrated in Radburn, NJ. In 1947-51, the originator of Levittown on Long Island, William Levitt, launched his post-World War I model for housing. Here, new social housing was its own zone, separate from other parts of a city or town. Levitt apparently said: “No man who owns his own house and lot can be a communist… he has too much to do.” It was this new cultural ideal – a suburban housing subdivision – that set the baseline for 60’s and early 70’s era housing. The trend continued to separate residential areas from industrial areas, at least in theory.

While zoning itself is a planning tool that is arguably many centuries old, zoning has increasingly shaped the look of our part of the state. But there were and continue to be what we would call today unintended consequences, such as racist policies related to red-ling. A further defining aspect of post-World War II housing is that there was an increasing standardization of components and parts for house building and the home-owning market. Standardization and prefabrication are two different things but both are technological and design movements that impact all aspects of architectural design and the profession as a whole by the 50s and early 60s.

I am conscious while writing this article that the terrible fires in California are still raging. While the damage in Pacific Palisades has been widely covered in the news and social media, the communities of Eaton and Altadena have also been very badly hit, especially Altadena, a town 15 miles north of Los Angeles that has a high proportion of black-owned homes. Included in the destruction is a housing complex, designed by modernist architect Gregory Ain that was racially integrated and used some prefabricated elements along with modest, site specific, landscaped grounds. This is his planned community at Park Planned Homes, sadly decimated by the fires.

In Amherst, post-World War II housing development took two different directions. The first trend coincided with a period of incredible growth at UMass where higher education acted as a stimulus for workforce housing along with well-designed dormitories and some distinctive high-rise developments planned for undergraduates. There was also growth at the other end of town with new dormitories for Amherst College (that would eventually supersede the fraternities) and Hampshire College. The history of student housing at the state university as well as Amherst’s private colleges probably deserves its own article. Suffice it to say that the social housing market seemed to be a safe investment. Even though this is not the subject of these articles, it should be noted that at the same time as these developments, the ‘second home’ market began to take off in places like the Northeast.

The uptick in local housing provision is also evident in the increasing number of private developments such as the pioneering area called Echo Hill South, dating to 1965. Private housing represented a parallel trend to the expansion of higher education institutions in Amherst. Taken together, these trends do so much to define Amherst’s identity as a town or mini-city today.

In 1968, another of these new housing developments was built just north of the growing UMass campus and was called Puffton Village; a place that “for the past 47 years, 900 UMass students have called home each year and hopefully thousands more can for as long as the apartments stay standing.” While the massing and form of the buildings is charming and scaled to the neighborhood, the sound insulation is very poor. Friends of mine living there in the early 1980s can attest to paper-thin wall construction. They moved to Amherst Fields, on roads like The Hollow and Pine Grove, off Belchertown Road. This was a housing development designed by Peter Kitchell Sr., built close by the Stavros Center, a pond and walking trails by Wentworth Farm.

There are many other Amherst housing projects of this era such as Orchard Valley (Glendale Road and Longmeadow Drive) designed by Kay-Vee Realty in two phases. More modest social housing, such as Brittany Manor, was constructed off East Hadley Road, and dates to the 1970s. Brittany Manor (now the Boulders and Southpoint) became the home of Cambodian refugees in the 1980s and eventually a Cambodian community temple was created here. The perception of the ‘mothership’ of UMass as a sort of mini city attached to Amherst Center developed during this era with its own graduate student housing at Lincoln apartments (demolished in 2022 to create the Fieldstone buildings.)

Affordable housing got a boost, nationally, in the late 1980s when the Nehemiah Housing Opportunity Grants (NHOP) program made federal grants available to nonprofit organizations that could then fund low-income families’s purchase of homes being built or rehabilitated. This happened almost at the same time as the Native American Housing Act finally gave the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) new responsibilities for the housing needs of Native Americans and Native Alaskans.

In the next article I will endeavour to bring the topic of social housing up to date. It is also the case that in writing about the this era (the 60s and 70s) I am also reflecting on my own era and probably displaying certain kinds of bias or preference. In order to address this issue more directly, article #4 will take a deeper dive into the period in terms of more personal history (related to housing) and the last article, will attempt to evaluate the present, especially with a view to issues of sustainability and historic preservation.

It’s always fun and informative to read Hetty’s historical accounts: following the links offered a deep dive into architecture way beyond Amherst that took me quite a while to resurface from! 😉

But, alas, did you overlook “the first new subdivision” in Amherst, sometimes known as “Jonesville”?

Developed by Walter Jones and built (largely) by “Two-Nail” (or perhaps it should be “Toe-Nail” for the diagonal nailing technique he used for the framing as well as the kitchen cabinets — I discovered that “the hard way”) Tony Conklin in the late 1950s on the former Harlow Farm.

The streets layout resembles a ladder whose rails are the east-west “main drags” — the eponymous Harlow Drive to the north, and the straight-away Van Meter Drive (named for the the UMass prexy at the time) to the south, joined by three rungs Ridgecrest, Hartman and Frost Lanes.

The neighborhood was designed mainly to affordably house many new faculty and staff who were getting started at UMass, and it still does that (along with a few UMass students nowadays).

And, IMHO, the view to the west from the end of Van Meter Drive is among the best in the Pocumtuk (Pioneer?) Valley: With just a little imagination, one can see things as they were 300 or even 3000 years ago, because one is standing on the eastern shoreline of what had once been post-glacial Lake Hitchcock.

The Cape-style house at 45 Hills Road is a Royal Barry Wills design.

The comments here are taken up in part 4 of the series. And here is a little more information about this history of people and their homes in Altadena https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2025-01-24/altadena-black-residents-impacted

This event appeared today via the nohocenterforthearts on Instagram. They are hosting a Community Forum: Northampton’s History with Housing Discrimination

Guest Speaker: Dr. Ousmane Power-Greene

Wednesday, May 7 from 5:30 to 7 PM

Don’t miss Dr. Ousmane Power-Greene, the E. Franklin Frazier Professor of Africana Studies and Professor of History at Clark University to discuss the history of housing discrimination in Western Massachusetts. Professor Power-Greene will place the most recent efforts to eradicate discriminatory housing policies and practices within the context of the long movement toward achieving equal rights in the United States. Light refreshments will be provided.

Event details and ways to RSVP can be found here — https://www.zeffy.com/en-US/ticketing/fair-housing-forum-northamptons-history-with-housing-discrimination

Please email anguyen@massfairhousing.org if you have any questions or need any accommodations.