The History of Housing in New England Part 4: A Sideways Glance to My Own Minneapolis Housing Story

The author's sixth grade class at Agassiz Elementary School, Minneapolis, MN (1968)

Amherst History Month by Month

This is the fourth in a series of five articles. Read Part 1 here, Part 2 here, and Part 3 here.

Writing about the era of post-World War II housing (in part 3 of this series) brings me up a little short as far as an analysis of the period. I think in part it’s because I witnessed this era in a more personal way, although in the midwest rather than New England.

In 1968, I traveled with my family from London to Minneapolis. The Beatles’ movie Yellow Submarine had just opened at the cinema in the UK. My parents were reading about the politically charged Democratic National Convention that was happening in Chicago at the time. What I know now but none of us knew then was anything about the post-War history of Minneapolis, MN and the pivotal 1948 election of Hubert Humphrey to bring the state “out of the shadows” as far as civil rights were concerned. This matters to my story and I will return to it shortly. As visitors, we were assisted in finding a place to live in the ‘City of Lakes’ through the efforts of administrators at the Minneapolis College of Art where my father was going to teach for the semester. My mum was going to help launch my brother and I into an elementary school and work on her own art projects. Their joys and struggles while finding their feet – so we kids could too – are now most compellingly at the heart of what I wish I had asked more about.

Our family stayed on the south side of the city in a wonderful, slightly beat-up, small, four-square house with a gambrel roof.

Photo: Google Maps

When winter came, the windows would get thick ice on them and someone showed us how to set pennies on the glass and then watch them slowly sink through the frosty skin of the ice. The house had a front porch with free-standing Ionic columns (since enclosed).

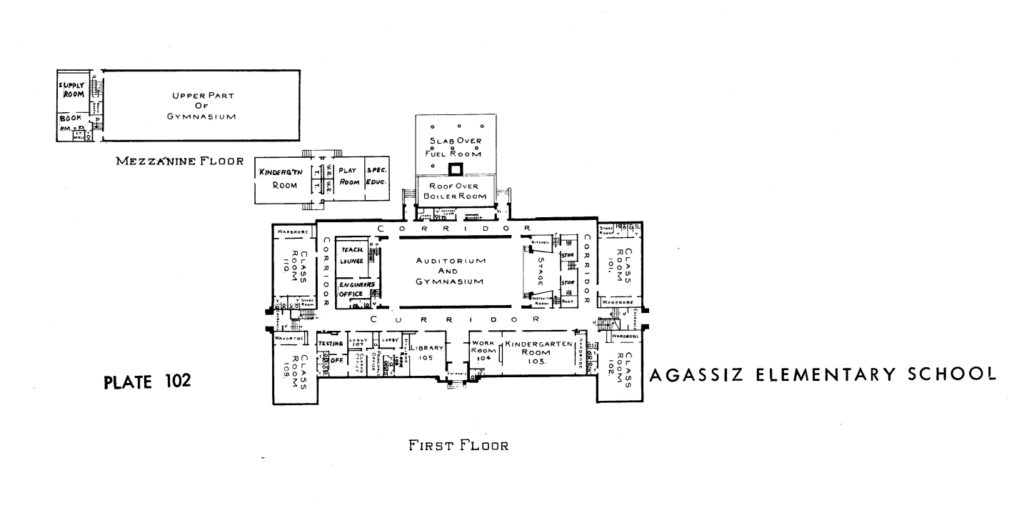

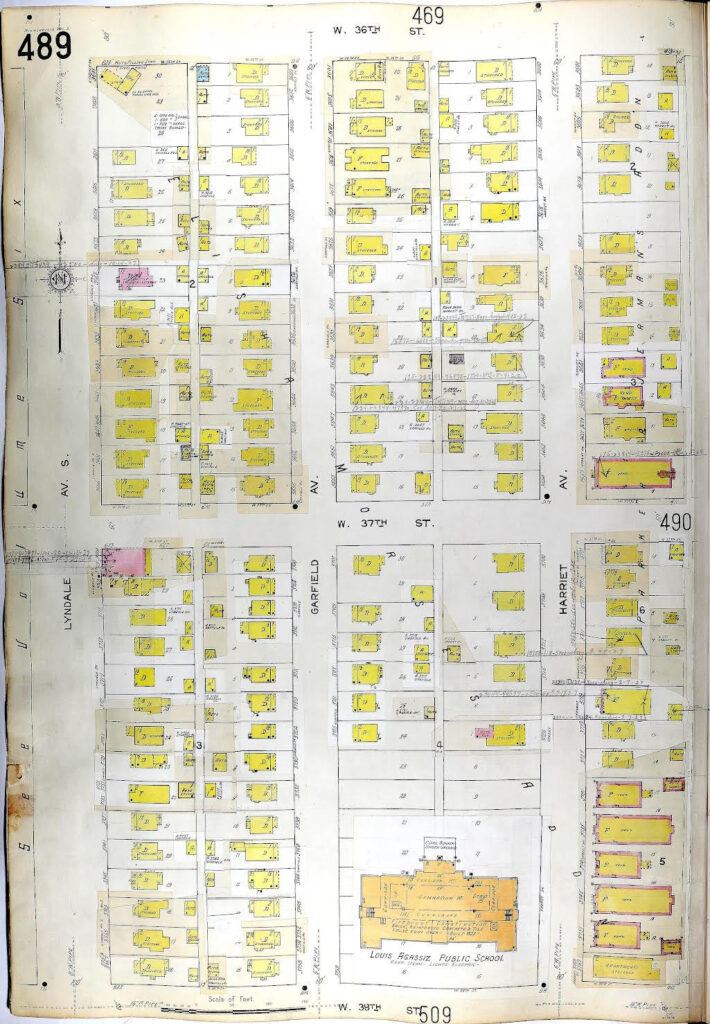

In the back yard, facing the alley was a garage but we didn’t own a car. The space had discarded drums and reels of wire and rope in it, and it would become the perfect spot for our neighborhood ‘garage’ band where we sang ‘covers’ of the latest hits. At the local public school named for biologist/geologist Louis Agassiz (1807-1873), my brother attended one of the kindergarten classes while I joined a sixth grade class with Mrs. Delores Hare as my teacher.

The Agassiz School had been built in 1922 and was associated with a city-wide program for what were then referred to as hearing impaired children. On the first floor, there was a large gym where we often went for square dancing lessons.

To my ten-year-old eyes, my classmates seemed like those in my local mixed-race primary school in London. I have since learned that some students were bused there. Maybe that included my square-dancing buddy – he was the best dancer; one of my first schoolgirl crushes. I remember his name was Anthony. Oops, Hetty, stick to the narrative! Built as one of several neighborhood schools before the Great Depression, the Agassiz School building was demolished in 1981 after suffering extensive damage during a powerful tornado that took off its roof.

This long aside starts to paint a picture of my introduction as a child to America’s housing history. We had landed in a residential neighborhood ‘in transition’ consisting of established single-family homes, and more recent duplexes and apartment buildings close to a busy interstate highway.

It was the era of “white flight” and that included from Minneapolis’s south side. It was only much later that I was told that the area was “transitioning,” which didn’t really reveal the deep anti-African American and anti-Jewish sentiments that were rife in the city at that time. Starting in the 1930s, Minneapolis was experiencing the Great Migration (the subject of Isabel Wilkerson’s important book The Warmth of Other Suns). Where we were living, African Americans had begun moving to south side neighborhoods like Bryant, Central, and Regina to escape the segregation and racist policies in the south.

The house we rented was located off west Thirty Fourth Street near Nicollet Avenue. As it turns out, it was just ten blocks away from the street corner where George Floyd was murdered in 2020.

I’m pretty sure that in our shopping neighborhood on Nicollet Avenue an ‘Ace Hardware’ store has replaced our favorite Ben Franklin “Five and Dime” store. We would go here after coming back on the bus from downtown where we’d fetch my Dad from work at the art college or at the Institute of Art where he often took us or his students.

Decades later, I try to think back to this time. The area had been populated in the 1800s by earlier immigrants from Norway and Sweden and then attracted newer BIPOC communities. The neighborhoods there had also seen the creation of several “Carnegie” style (Neoclassical in terms of their architectural design) public libraries. My brother and I were interested in US history, although this interest was framed by the Laura Ingells Wilder stories and by movies of the “wild’ west. We were also interested in who had lived here first, the indigenous peoples of the region. Perhaps one of the most memorable things we experienced was spending time with our babysitter who was Ojibwe and one of my Dad’s graduate students studying sculpture. This personal relationship complimented the trips to the local museums to see dioramas of native tribes which we realized was not an accurate representation in terms of our lived experience.

Recently I learned that in the summer of 1968, “roughly 200 members of Minneapolis’s indigenous community gathered to address…police brutality and racial profiling of Native Americans.” It was, in fact, the era of the birth of the American Indian Movement (AIM) which became the driving force behind the modern indigenous civil rights movement. “We decided we would no longer be pushed to the margins,” said Mike Forica, chair of AIM in 2024.

Responding to My Readers: On Jonesville and Royal Barry Willis

In the last column of this series, I will be returning to the main narrative of the history of housing in New England.

I also want to pick up some of the threads of earlier articles, and respond to the comments of some of my most faithful readers.

I wanted to share some information about “Jonesville” that is near North Amherst and the Red Gate/Hills Road neighborhood that was mentioned in a comment by Rob Kusner in Part 3 of the series.

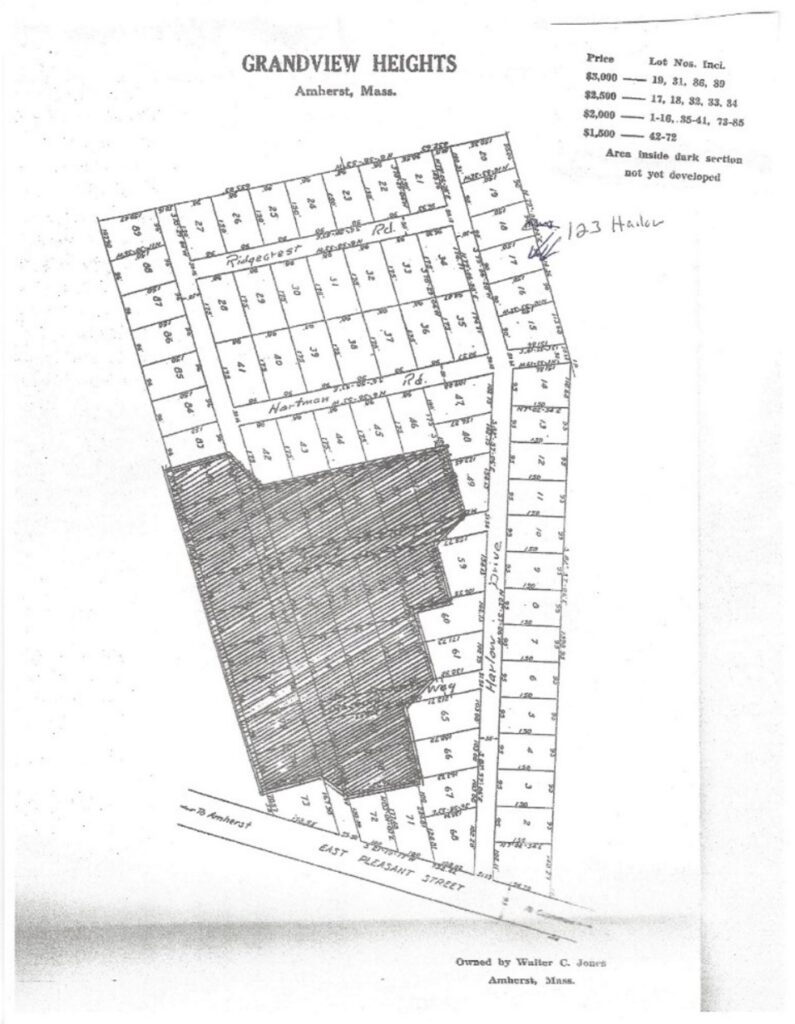

The so-called Jonesville subdivision – actually, Grandview Heights, was created off East Pleasant Street in 1952 by Walter Jones. One of the streets in the sub-division is named for his wife, Sarah Hartman Jones. It is, as Kusner describes, “a ladder” of streets that was once owned and managed by the Harlow family as farmland for the Jerseydale Dairy Farm. Begun in 1908, the Harlows had 100 Jersey cows and won prizes for their milk. The land west of this first Amherst subdivision is still farmland today, managed by UMass as part of their Student Farm. John Gerber, writes about this in his blog.

The Red Gate Lane and Hills Road area is a distinct neighborhood that deserves to be its own Local Historic District if that is something that the residents think would help to preserve the character-defining aspects of their neighborhood and maintain its history. I have heard that this section of town was significant as UMass grew, in terms of its faculty population, and was a welcoming area for non-WASP new residents of Amherst. I have addressed the significance of this part of the town elsewhere and, mixed in with its modernist, ranch-style homes is a good example of a copy of a Royal Barry Wills design, (that Hilda Greenbaum points out) is located on Hills Road, embedded in streets that have more homes that look like houses designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.~

Thanks for adding this interesting coda, Hetty!

Much of the shaded area on theGrandview Heights/Jonesville plan has very high groundwater levels (it would have been wet meadow back then, fed by springs flowing from the higher ground to the southeast) and may have been built later after the storm sewerage system was installed there — presently these “run” like an underground creek much of the year! — and once landfill from other parts of the development became available.

Pre-1950 USGS maps show a surface stream there; its remnant now emerges from a culvert further to the northwest, and crosses North Amherst Community Farm before passing under North Pleasant St and Puffton Village in another culvert and merges with the Mill River near Meadow St.

Much of Amherst Center, as well as the Amherst College and UMass campuses, also feature these culverted streams. Wetlands laws were different — nonexistent!? — back then. Perhaps this aspect of Amherst’s architecture — its landscape architecture — is worth a future series…?

* * *

And who might be the young lady — looking directly at the camera — front-row-center in the opening photo? 😉

yes, that is me staring at the camera. The photo was posed and my fellow students were asked to look at me, which for a ten year old was really embarrassing. “Ms. Hare, really???” It was intended perhaps as a gesture of welcome. Now that I am learning how complicated the “Great” Migration was for blacks coming north to cities like Chicago, Philadelphia and yes, Minneapolis, this welcome is more cringe-worthy. More about this in this link to the new PBS series with Skip Gates about Great Migrations: People on the Move https://www.pbs.org/video/exodus-1qhprk/

More about this historic era from the organization Wayfinders on their Facebook page “Despite racism in real estate and banking – and racially restrictive deed covenants, which can be found in western Massachusetts today – Black families in Maplewood, Minnesota, found homes. Journalist Lee Hawkins grew up in this sleepy suburb of St. Paul. His podcast Unlocking the Gates tells the story of how a single land transaction in 1948—a white farmer who sold 8 acres to a Black couple—created a domino effect by which, ultimately, families like the Hawkins’ could begin building wealth.”

https://www.marketplace.org/2025/02/12/black-families-maplewood-minnesota-subrubs-racist-housing-practices/?fbclid=IwY2xjawImBs5leHRuA2FlbQIxMQABHVOPQuipb-XIUF9z4U9d5RrDfRQT_T61vxo4uI5yX0Ydo0pFRnfOjHem3Q_aem_aGwf5XB_tkiTcjf-zsQf_w