Introduction to the Mill Histories of North Amherst

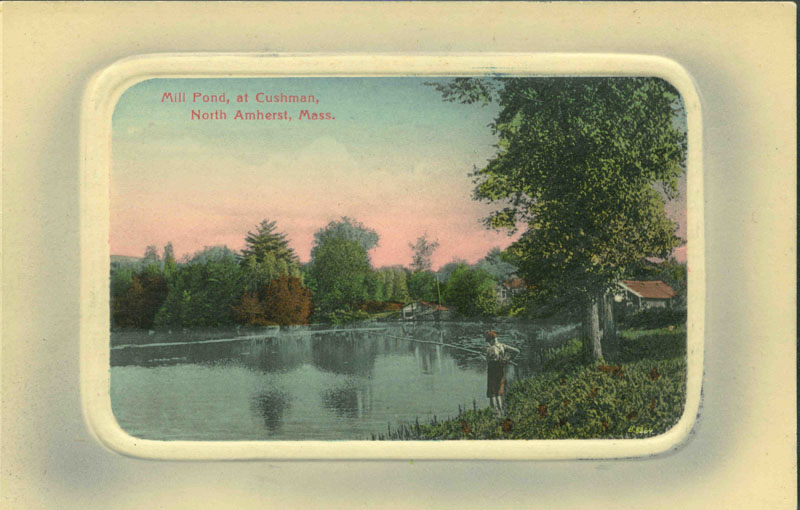

Postcard (ca. 1914) entitled Mill Pond at Cushman. North Amherst, Mass. View of a young person fishing at Mill Pond in Cushman. The pond was at the corner of State Street and East Leverett Road and was the water source for the mills downstream, including the Roberts Mill. Edgar T. Scott (1858-1940). Photo: digitalamherst.org

Amherst History Month by Month

This article is the first of two on the history of mills in North Amherst

Preface

The chilly, drizzly, or balmy days of early spring remind me of the weather I grew up with in England. Lately, I’ve been driving around the Northampton villages of Leeds and Florence as well as hilltowns like Chesterfield and Goshen. It is mud season but not quite spring yet. It’s posted that drivers should avoid some of the dirt roads. I take these signs seriously.

Back in the UK, spring is further along and a school friend shares photos of a Mothering Sunday outing (always celebrated in England on March 30th) to The Mill House. The Mill House, an historic water mill with restored gardens and comfortable outdoor seating, is near Basingstoke in the heart of London’s home counties. It seems that my friend has gone for a walk by a canal before an anticipatory pub lunch [“Great ales and super Sunday Roast”]

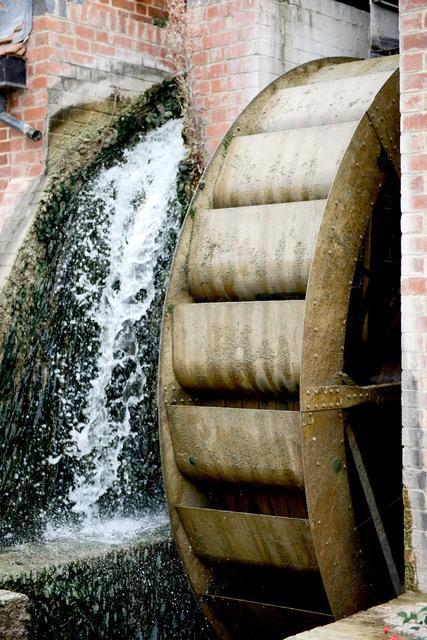

The Mill House’s architecture dates to the 18th century, but apparently it is mentioned in the Domesday Book from 1098 as “the King’s Mill.” Today, it sits by the mill race, and even the mill wheel — the source of converting power from the waters — survives. A win for historic preservation.

This isn’t just a trip down the bunny hole about old friends and/or bookmarking the Mill House for an in-person visit, perhaps, on a future trip to the old country. It is the mill itself — the image, its history — all that! Homing in on maps and photographs leads me to recall moments in my life when we learned about the early industrial beginnings (and mills) of New England; first, in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, where I raised my family (learning that it was the so-called birthplace of the American Industrial Revolution), and now in North Amherst.

Mills have historically been tied directly to rivers and to waterpower in England as well as New England, although over time they could function just as well with sources of steam or electrical power. (Think: Tennessee Valley Authority) Many historic brick mill buildings in New England were converted to electrical power before being adaptively reused, while others didn’t survive the 1800s — many were made of wood — and if they did, they didn’t survive urban renewal in the 1960s and ’70s. The mills in North Amherst, which are hard to imagine today because the buildings are gone, historically used a mixture of water and steam power. Rivers like the Mill River/Cushman Brook in North Amherst were also used as an outlet for waste products, especially mills used in paper-making businesses.

In pre-industrial economies, people built mills over naturally-occurring waterfalls or constructed dams to produce much-needed staples like flour from wheat or corn (grain/grist mills), for wood (sawmills for fuel and lumber), and wool (fulling mills) (for textiles). In the following paragraphs, I will cover the history of some of the mills in two areas of North Amherst over a period of about 185 years.

The Historic Mills of North Amherst: Cushman and the Flats.

There are four discrete areas of historic mill buildings (five if we include Westville) in North Amherst. What we know as the northernmost end of Cushman by East Leverett Road today, is the first area. Here was a place, almost to the town line with East Leverett, where there were the “greatest falls,” where the force of the water falling could turn mill machinery to mechanically grind corn or work a fulling operation. There was a grist mill here by 1727 and, by 1798, “several hundred rods distant from the present Cushman Bridge,” a fulling mill. This industrial structure turned wool (the raw material) into a more durable product with denser fibers that were warmer to wear. It was owned first by Ebenezer Ingram and later by his son Peter, and processed “the dressing and finishing of cloth.”

Rights and access to resources like the natural falls at this and other places along the Mill River, which was known as Factory River in the early 19th century, was increasingly coveted over the next decades. By the 1780s and ’90s, New England, that was full of both big and small rivers, was filled with small mill operations – grist mills, saw mills, and fulling or woolen mills; the privileges or rights to create raceways and dams to harness water power and make production more efficient, were sometimes hotly contested and sometimes litigated. If your rural community wasn’t a historic seaport and didn’t have access to trade routes (or a trading center), you likely didn’t have a general store where you could purchase said grain and cloth; such a place would come a bit later, in the early to mid-1800s. This meant that you and your family relied on a grist mill or saw mill or fulling mill as part of a system of self-sufficient production. Natural resources were worked locally, water was harnessed to waterwheels, etc. to make staples to help communities survive.

Conditions were very different for local indigenous people, who understood the Mill River as a living entity rather than as a resource to be worked, and managed. Although white, indigenous, and enslaved and freed peoples in the 1700s in this area all needed food, fuel, clothing, and shelter, the lived experiences of each race were different. Local (Indigenous) people had been mostly deprived of their homelands by the end of the 1700s. In her essay ‘Native Presence in Nonotuck and Northampton’ (2004), Marge Bruchac mentions local Indians in Amherst and Hadley who were fabricating both handmade baskets and splint brooms. The North Amherst area had not been a native “homeland” in the same way that homelands in the meadows by what is now Hadley and Northampton had been. But the Mill River was a place to rest on travels through the region and its presence was identified by another name in a variety of native languages. Fish from the falls and sources of other food and shelter from the woodland had been familiar here to Algonquian, Pocumtuck, Nonotuck, and Nipmuc peoples for thousands of years. Well-established and sophisticated trade routes and trails older than the colonial era existed although these trails and networks had been impacted by wars and diseases brought by colonists. Their understandings of the significance of the Mill River’s waterways (and other elemental forces like earth itself, the wind and the sun were and still are complementary systems that exist to this day.

Lisa Brooks, https://ourbelovedkin.com/awikhigan/revolt-map?path=revolt

Lisa Brooks, https://ourbelovedkin.com/awikhigan/revolt-map?path=revolt

The Mill River Project

The Mill River Project, under the leadership of Meg Gage from the District One Neighborhood Association has been researching the specifics of North Amherst’s history (specifically the Mill River) and more especially its industrial history from about 1700 to about 1940 since late last summer. While this history has always been in the material culture record, what we have uncovered has been akin to a lost world because this part of the history (unlike my example of The Mill House in Basingstoke) no longer exists anymore physically, offering a material embodiment of what once was. And the era is also further back in time than the tellings of oral history testimony. This is why our historical research of documents, maps, and historic photographs at places like the Special Collections of the Jones Library has been so important.

Two public events so far have introduced people to the project: a late summer potluck picnic in 2024 at the Mill River Recreation Area invited folks to see photographs and maps and begin to get involved, sharing information about DONA’s sponsorship of the project, and this past month, one of our leadership team, Bryan Harvey, offered a presentation of what we’ve been learning, specifically about North Amherst’s industrial past. The occasion was a History Bites program with standing room only. This popular lunchtime lecture program is offered by the Amherst History Museum and is usually held at the Bangs Community Center. Harvey stressed that mill sites in North Amherst were at one time “intensively industrial.” It is hoped that a final phase of the project will include the launch of a website, online resources, and more outreach, as well as real-time programming. For the purposes of our study, the Mill River Project areas comprise:

1) North Amherst Center

2) Summer Street and Factory Hollow (below Puffers Pond and its waterfall on Mill Street.

3) “The City” that we now know as Cushman.

4) Westville (the neighborhoods nearer to Route 116).

Alongside the mill buildings that used to exist, it is worth recalling other kinds of architecture that characterizes this part of Amherst that IS preserved today. This includes the few treasured homes demonstrating the First Period architectural style in North Amherst (First Period is usually dated from 1675-1775) and there are many interesting homes and housing (with their own stories to tell) from the early to the late 19th century. The second of my two articles for the Indy will look more specifically at workers housing in North Amherst but for this article, I want to give credit where credit is due and say how fortunate we are to have the following homes preserved nearby. These are: the 1728 Boltwood–Stockbridge House (82 Stockbridge Road) acquired originally by the Massachusetts Agricultural College and now part of UMass; and the 1737 Eastman House right on Montague Road, opposite the Cherry Hill golf course.

A further First Period home right in Cushman itself is known as the Samuel Henry House, built in about 1770 at 107 Henry St.

One particular area of interest in terms of historic mill buildings in North Amherst is the Factory Hollow neighborhood. I am indebted to the project’s historian who did the lion’s share of the historical research for our project and this is how we have documented the site for the project so far.

It was here in 1809 [on the corner of Mill Street and Summer Street] that a local thirty-something farmer called Ebenezer Dickinson constructed a three-story wood frame cotton textile/yarn mill. As this was/is the first mill in North Amherst that shifted to textile production rather than the earlier staples of wood (for fuel and lumber), wool, and corn, it is worth mentioning the wider context for its appearance. All of the people involved in the Mill River Project agree that it is a pivotal story for this part of Amherst.

A North Amherst textile mill made sense due to the prevailing tensions between England and America between 1810-1830 that boosted textile production to the top of Amherst’s newer industries. Imports of English cotton cloth were stopped by the Embargo and Non-intercourse Acts and the War of 1812, opening up American markets to domestic producers. Ebenezer Dickinson wasn’t the only New England investor who grasped this potential, believing the time was now right to build spinning mills for textile production. According to George Cook, the pastor of the North Congregational church from 1839-1852, he remembered that the Dickinson-Amherst Cotton Factory was painted yellow and so were the associated boarding houses built for his workers.

Despite the timing of the new textile mill, Dickinson incurred debts and the mill was put up for sale. Dickinson had to answer suits brought by Noah Mattoon, Lucas Field, the state of Massachusetts, and his own brother Abijah Dickinson relating to the business losses associated with the new mill building in Factory Hollow. Reading stories like this always gives me renewed appreciation for the local leaders of our business community in Amherst and the risks they carry.

In May 1815, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ordered Dickinson to list his property preparatory to sale to satisfy the debt. Perhaps desperate, he broke into the textile factory he had once owned and stole a quantity of cotton yarn. Dickinson was married by this time to Abigail Barrows Dickinson and they had five children. An officer with a search warrant discovered the yarn in the garret of his house [I wish I knew exactly where they were all living at the time], and the entire family fled to Charlestown, Ohio. In May of 1816, Dickinson wrote to his brother, Abijah to say he had been ill but that he had also found a way to purchase an apple orchard [the influence of Johnny Appleseed?]. Ebenezer asked Abijah to sell some Amherst land he still owned to continue to pay off his debts. He hoped to “make awl things Rite” and return to Amherst with Abigail and their children. But he died within a year of his arrival in Ohio. Tradition held at the time that as he fled, he had laid “a violent curse on Factory Hollow,” a wish for the destruction of all future mills built there. And indeed, his mill burned in 1842 and within just fifteen years, six more textile mills in North Amherst burned. It was an inauspicious beginning although mills in other parts of North Amherst had better outcomes.

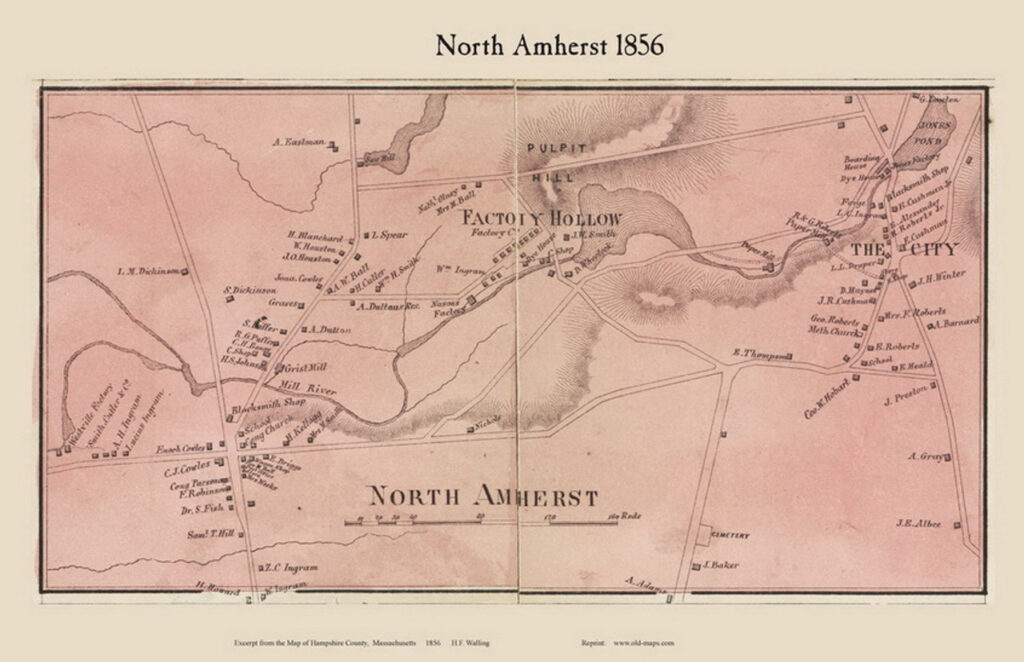

Factory Hollow and Cushman were two small, but thriving, mini-industrial hamlets-in-the-making and there was soon a blacksmith’s forge that linked the two mill districts along the river. Production further diversified in 1830 with the presence of an iron forge owned by Alvah Barnard. Here he made flange-bearing railroad frogs. Industrial processes were so prevalent that the Cushman Brook and Mill River of today was all known as Factory River (as seen in the map detail below.) In all, North Amherst would have several historic mill districts and five blacksmith shops, one of which was right by the site that would become the North Amherst Library.

While North Amherst’s first small mills had been for processing staples like wood or grain, it became a place where other kinds of industrial development were envisioned. This vision has come right down to the present day. The origins of this vision can be seen in the tragic story (and “curse”) of Dickinson’s early textile mill at Factory Hollow (on Mill Street and Summer Street today) but also in the slow growth of secondary industries such as the newer paper-making mills, still constructed of wood, that began to appear all along the river. These mills continued to use hand-powered processes at first but over time, as the 1800s wore on, became more heavily mechanized.

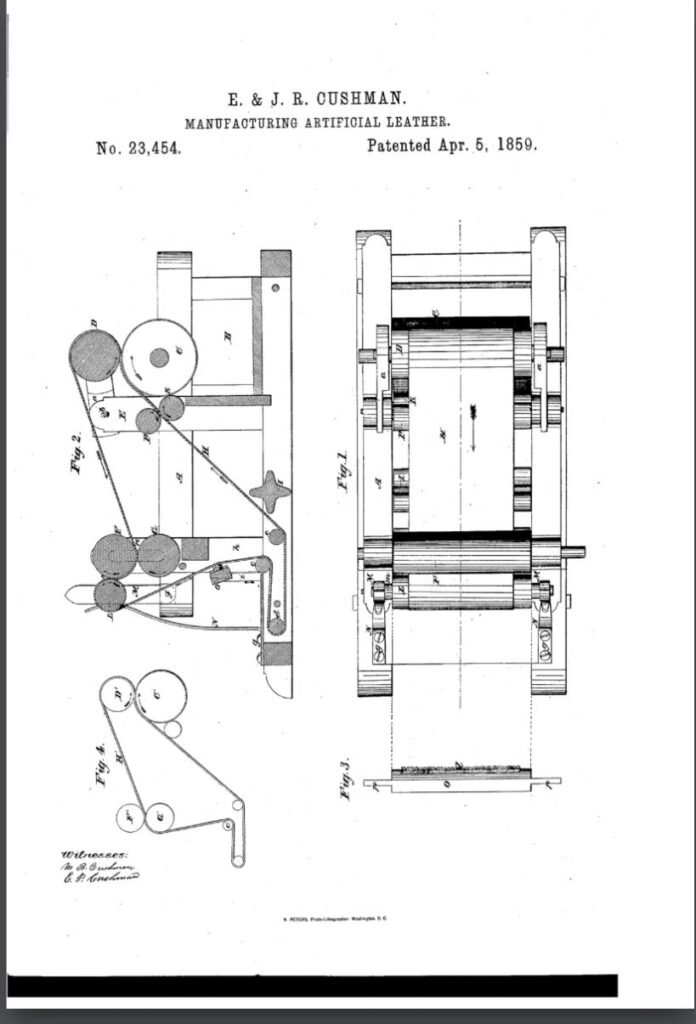

A paper-making wood-framed mill was constructed in 1835 in North Amherst, almost at the town line with Leverett by two brothers, John and Ephraim Cushman. It is hard for us today to understand the significance of this kind of production process; the paper was made from rags or sometimes from wood pulp. In early 19th century New England, it turns out that rags were in short supply; some firms even imported rags from Europe to make sure there was sufficient raw material. With a small workforce, the first Cushman mill owners produced products like cardboard and something called strawboard. They cleverly survived the national financial panic of 1837. A patent owned by Cushman in 1859 helped to transform what had been a hand-powered technique that involved drying pulp into another product.

[https://patents.google.com/patent/US23454A/en

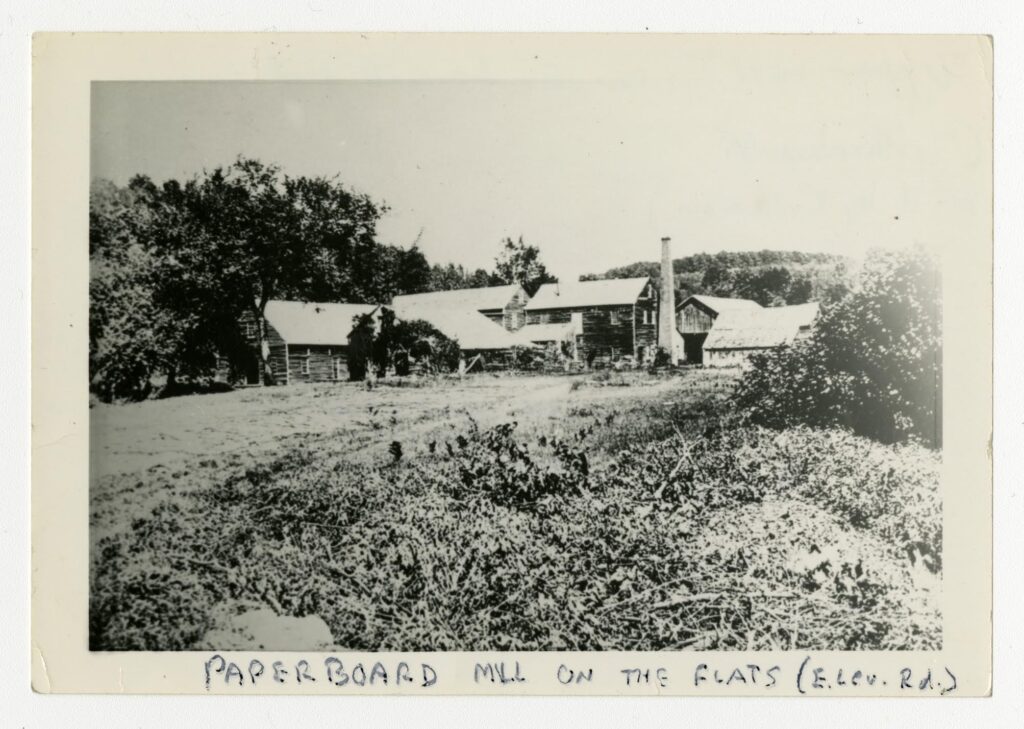

Over time, the Cushmans diversified, making something that could be pressed to form the insoles of shoes. A further diversification – a product called button board was created that could literally form shoe buttons for the shoes of Victorian women in the mid-1800s. This is what the mill looked like. It is an historic photograph I treasure because the building is now gone.

We know that the Cushman mill owners lived near their mills along with the workers they hired. We need to learn more. We know that the workers needed to be able to walk to work for this was an era just before the train and trolley came through town. Things changed rapidly in the post-Civil War period, when the Mill River itself was transformed by a series of terraced pools “each backing upstream to the base of the next dam.” This created more opportunities for water-powered industrial development. Along with the forge that was located near the old Cushman mill, the family constructed a new paper mill that became known as “the Red Mill” downstream. The Red Mill hugged the river as well as the dirt roads at that time and was the dominant feature in what was a very small hamlet compared to the areas of North Amherst below Puffers Pond (Factory Hollow) or North Amherst Center (located around the intersection of North Pleasant Street and Pine St/Meadow Road.)

Two other paper mills in what we know today as Cushman were built by the Roberts family; one of these was their Upper Mill that famously sent paper by oxcart to Albany, New York for use in the publication of Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune. Greeley did say “Go west!” and thus the paper went. The Roberts Lower Mill is clearly sign-marked today from Pine Street on the Robert Frost Trail. It is the archaeological and surface remains of these two Roberts mills that were studied in the first phase of the Mill River Project. Grouping all the paper mills together (in our minds eye or on a schematic map of the area) you can imagine perhaps a really significant group of clustered industrial buildings and structures solely for the manufacture of paper and related paper products. The area benefitted from the completion of the railroad line linking Cushman to Millers Falls in 1866. Before the crash of 1873, four paper mills along Mill River, with a fifth in Westville near what is now Meadow Street, produced $85,000 worth of diverse paper goods the second largest recorded industry in Amherst after palm-leaf hats of East Amherst.

Paper-making production also occurred at Factory Hollow (at the east end of Summer Street) where Ebenezer Dickinson’s ill-fated textile mill had been located (it burned in 1842, was re-built but did not survive a flood – it was more like what we call today a series of freshets – in 1863.) That same year, another Cushman mill owned by the sons of Ephraim Cushman began making newsprint, then bags and papers out of wood pulp called manila paper (papel de manila). The paper shortage in New England only came to an end in the 1870s. So this was a place of real industrial significance. Like the Dickinsons, the Cushman families built on an established record of eighteenth century proto-industrial output in this location; there has been a Grist Mill at Factory Hollow built in c. 1771 by the Williams family. In 1830, another sector of industrial production was added when a mill for planing wood into boards and related wood products was opened by the Graves family. They made window blinds and sashes and doors. Significantly, the Hills Hat Factory (based in East Amherst, and begun in 1856) opened a branch mill here that functioned as part of a very successful enterprise for the whole town of Amherst. Remember, gentle reader, that Factory Hollow had been the site of the 1809 Ebenezer Dickinson Cotton Factory so perhaps the curse had outrun itself? We have come full circle for this article. Here is a picture of the Graves Planning Mill. It must be remembered that a small area of South Amherst, called Nuttingville, had a small group of factories making things like planes, drills, and lathe equipment.

To conclude for now, it is interesting to note that development of an industrial-based manufacturing economy in North Amherst led to the repurposing of some existing mid 19th century homes where workers could rent a room (are these the original ADU’s of our town?!). There were also a spate of purpose-built houses for workers that survive, constructed along State Street (a road that was built originally to access the north side of the Mill River) and Summer Street. Some workers housing was taken over by the L. Hills Hat company. But it was the Cushman Red Mill (1859) that outlasted Dickinson’s curse. It was painted red like an agricultural barn. Unlike their old mill upriver, the Cushman Red Mill became something of a local landmark as it survived into the early 20th century. Locals remembered that during the Civil War the owners had flown ‘Old Glory’ from its red, white and blue cupola. Cupolas are the small, decorative structures you can see on top of some barns and houses from this era, many of which survive to this day.

As these little North Amherst mill hamlets grew, and manufacturing businesses held their own, other kinds of community activity strengthened their ability to thrive, including cooperative societies offering dry goods [the Workingmen’s Protective Union Store (1847)] and civic improvement programs. Some of the first worker housing on Summer Street was acquired around 1863 for the workers of the Cushman paper mills. Ten years later, in 1873, another financial depression hit the country and local bank closures in Amherst alone lasted for about five years. After 1878 the Cushman enterprises passed to Avery R. Cushman and his son Charles. They employed “20 hands and [made] 3 Tons of straw-leather and button board per day.” These more recent generations took over the management of the North Amherst mills,, dealing with fires, re-building when necessary and if financially feasible, and hanging on until another, pivotal, national financial slump in 1893. The North Amherst fire station – called a “hose house” on Pine St was finally built in 1902-3 and perhaps helped in part to lessen the number of fires at these mill buildings.

This is all pretty overwhelming. Thanks to Meg Gage, Bryan Harvey and all those involved in recovering and documenting North Amherst’s history. and thanks to Hetty Startup for this compelling compendium of narrative and photography.

There is lots to think about here that is pertinent to our current dilemmas about development and historic preservation in Amherst. I am particularly impressed with the importance of thinking about buildings in their settings when we develop and redevelop land and properties. Years ago Town Meeting assiduously voted to protect and preserve a historic East Street house but was careless about protecting its immediate surroundings. I fear the same thing could happen on Amity Street where most of the concern about historic preservation in the proposed Jones Library project seems to focus on the building itself and not on the building in its setting.

But my larger concern is who is going to care about Amherst’s history in the decades to come? We are building now largely for transients, and have been careless about protecting our character as a place where families can live and children can grow up. This character is not inconsistent with our need to provide housing for students and other temporary residents of an educational community, but it doesn’t take care of itself. In these days of density and infill we need our boards and committees to be more foresighted in their thinking and planning than they have shown themselves to be recently.

Besides the changes happening over the past 30 to 40 years which Michael thoughtfully decries, and the impacts of colonial settlement and industrialization which began 300 to 400 years ago as Hetty carefully describes, there was also great geophysical change that occurred roughly 3000 to 4000 years ago as the great post-glacial lake (now referred to as “Lake Hitchcock” stretching from the Holyoke Range many tens of miles to the north) drained and re-established these alluvial plains and great meadows along the meandering Connecticut. This much earlier period also laid the foundations for another industry — sand mining — near the Mill River valley, as the wind-blown fine sands and water-borne coarse sands on the now-exposed lake-bed accumulated on what had been the lake’s eastern shore near what would have been the mouths of the Mill River when it emptied into that post-glacial lake….

Thanks to everyone working on this project–Meg, Brian and all the others. This is important work and brings richness to our community.