The Mills and Industrial History of North Amherst, Part 2

Cushman Market and General Store, North Amherst. Photo: Facebook/ Cushman Market

Amherst History Month by Month

Read Part 1 of the Mills and Industrial History of North Amherst here.

The heyday of North Amherst’s industrial history relied on the Mill River and the presence of things we can’t see today – the mills themselves. But other elements for success were its workforce of laborers, paid and unpaid, women as well as men who worked here; and the built infrastructure that supported all this industrial activity that in part survives to this day. Much of the land and the industrial history of this area is now protected by the town of Amherst on parcels managed by the Conservation Commission and/or by other agencies, both at a state and local level; and the area is also supported and protected by a group of important private local stakeholders and businesses.

Blacksmiths

Since I first got involved in District One Neighborhood Association (DONA)’s Mill River Project, I have been interested in what this small research group would learn about the historic workforces of North Amherst. I have recently bought pansies from the Zuzgos, who own Twenty Acre Farm in Hadley, but they reminded me that they used to work in North Amherst. They remembered tobacco growing in the fields behind the Black Walnut Inn and what is now Puffton Village. [Listen to this wonderful interview by Monte Belmonte from last year here.] I doubt that industrial successes would have happened without the help of local farmers in both Hadley and Amherst (this part of Amherst was once part of Hadley). Farming families in the mid to late 1800s had been located on Flat Hills (the King family) and Market Hill (the Kellogg family) Roads. One set of skilled people who apprenticed to a particular trade were also important – for their labor, their products and their services. These were North Amherst’s blacksmiths. In the late 1700s and early 1800s, blacksmiths were always in demand, especially for the agricultural implements they could fashion. You would need a blacksmith to shoe your horse(s) or repair the wheels of your wagon. Towns like Deerfield, Hadley, and Amherst often had more than one blacksmith, and “…some specialized in producing edge tools or machinery. Others shoed horses or took in work related to the carriage trade, by turning to wheelwrighting and repairing vehicles. Many blacksmiths did general iron work, repairing manufactured and imported tools, …making hardware and other metal items needed in the community.”

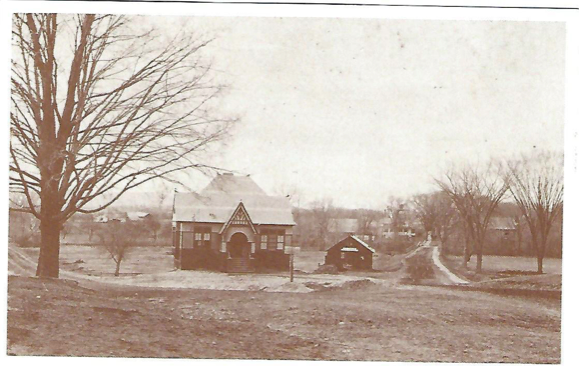

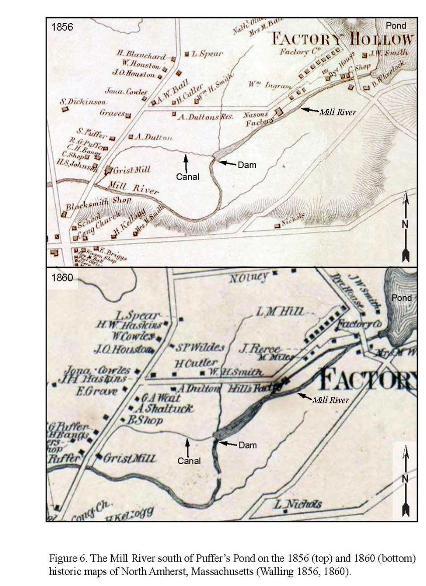

In the first of these two articles about DONA’s Mill River Project, I mentioned Alvah Bernard and his forge that operated in 1830 on the river between Cushman and Factory Hollow. Bernard was the one who made railroad frogs (how could you not be curious about that?). The Mill River Project’s researchers have uncovered as many as five different blacksmiths working in North Amherst over the time period of its industrial history. It seems that there was also a blacksmith called Henry Kellogg who in 1843 leased a property/blacksmith shop very close to the site of the North Amherst Library today. The shop may have been made of brick or stone since these were the preferred building materials for this dangerous trade. (The granite-block blacksmith shop at Old Sturbridge Village, dating from 1810, comes from Bolton MA.)

The resources necessary to set up a blacksmith shop intrigues me as a topic, perhaps because I grew up in a household with a father who worked from home. He was a sculptor, and he mostly worked out of the front parlor in our home, using it as his studio. When my brother and I were small we would peek in, visiting if permitted, checking out the work in progress, playing with his vice and messing with bits of wood lying around. Of course, a blacksmith’s shop (and forge) would be a much more dangerous place for curious children to be. And to become a blacksmith you had to have built up the body of knowledge associated with your trade as well as a set of tools: a bellows, the anvil, a bench vice and a foot vice, and all sorts of drills and wrenches, as well as the actual furnace and a stove pipe. In fact, the capital outlay for such a trade as well as the costs of an apprenticeship would be considerable for most people.

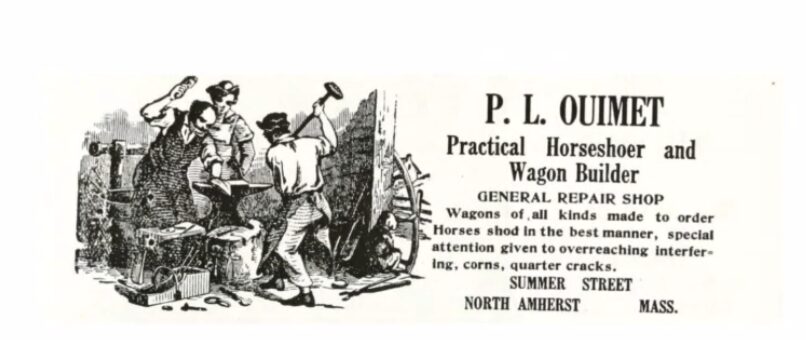

There were other blacksmiths who worked on Pleasant Street and also on Summer Street. Below is the historic trade card of the Summer Street blacksmith.

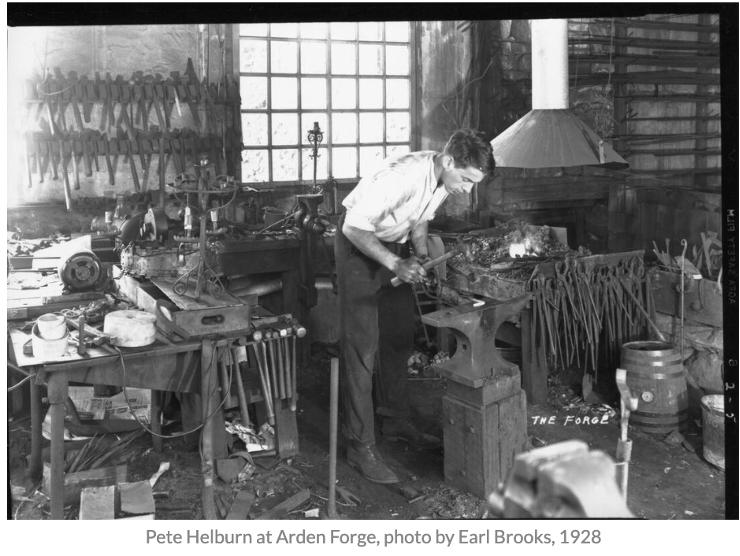

These days it is often only possible to see this kind of skilled tradesperson working in a craft-based studio during an open house or at places like historic sites or house museums. Photographs of this kind of activity (one vintage and one from a piece of historic film footage come from the working forge at a historic arts and crafts village in Arden, Delaware and this suggests what North Amherst’s smithies looked like.

Dams and Canals

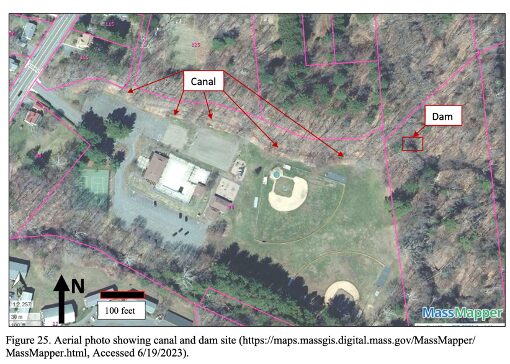

North Amherst’s historical industrial hub also owes its history to larger historical shifts in New England in the late 1600s through the late 1800s – when the Mill River area was extensively and (from an ecological perspective) quite violently worked – representing a series of economic interventions that proved so consequential for current generations. The waters of the Cushman Brook and the Mill River have been dammed many times; there was even a canal that was built along its path at one time (still visible from the Mill River Recreation Area.) One of the earliest dams from the early 1700s (not made by beavers) was a log crib dam [made using a timber frame filled with rocks, stone, and gravel) that impounded water to power both a grist and a sawmill in the north-east part of town. Later dams, marked on historic maps of the area, are evident downstream.

Housing for Workers

What also sustained North Amherst’s nineteenth century mills was the presence of nearby worker housing. While its mill buildings were usually made of wood, three stories high and 4 bays wide, the housing for its workers was designed to be scaled down and far more modest in appearance. Historians have commented that it is this effect that gives Cushman its architectural coherence today. The North Amherst wood frame dwellings were very different from the purpose-built, brick housing built in the 1840s for workers in the largest mill towns in Massachusetts: the new textile town of Lowell needed boarding houses for hundreds of farm girls, recruited from nearby farms to work in the spinning sheds, and it was felt at the time that they needed to be supervised by a boarding mistress or keeper.

The mill owners in Holyoke were also in the business of housing large numbers of workers many of whom were immigrants from Ireland. The Hadley Falls company housing was extensive, made of brick, and still stands on the intersections of Lyman and Canals Streets.

Worker housing in the Mill River Project area, by contrast, is much more modest in scale but some of it is still preserved today along Summer Street and State Street where there are two remaining dwellings that date to the mid 1800s.

There are other examples of early to mid-nineteenth century single family homes, where workers could board and one of these is the Peter Ingram House in the Greek Revival style, at 51 East Leverett Road.

By about 1873, a full one third of the housing in Cushman was owned by local mill businesses for their workers. There is a pleasing visual coherence in this area in terms of architectural style and building materials. Housing has also been preserved on Summer Street, built originally for the workers of the paper mills, but then bought and repurposed by L. Hills Hat factory workers; these homes are all located east of a stream, a little tributary of Mill River, and are located at 130, Summer Street, and at 154 Summer Street, known as the Knowlton House, 158-164 Summer Street (currently for sale) and at 182 Summer Street on the corner with Mill Street in a small cottage known as the Dwight Graves House.

For these historic communities to thrive, other kinds of structures came to define the village core, such as small dry goods stores on Pine Street and Bridge St and a local post office (that we know today as the café and store, Cushman Market and Cafe. One house, 86-88 Bridge Street is an imposing Greek Revival style that was built as the Lewis Draper tavern.

By the time the North Amherst mills were less profitable and were being outperformed by larger mills in Turners Falls (also known as Great Falls and the site of metalworking and machining mills), and the Holyoke mills (where the first profitable canal in our area was located at South Hadley Falls0 these North Amherst hamlets at Cushman and “The City” (Factory Hollow) continued to live on. The Cushman Red Mill survived for a while as a social hall where people flocked to dances on Saturday nights. There was the famous Cushman Clam club, a men’s club that is still identified as a site on one of the trails by the common, opposite Cushman Market. There were still some tobacco barns in this part of town (one survives on Pine Street). Broom corn continued to be grown for brooms and also was a raw material that had been used in the making of some kinds of wrapping paper. Located near the building that was the Cushman post office and is now Cushman Market were a number of purpose-built structures (factories rather than mills by their appearance) that made tissue paper – not the kind we think of today for gift wrapping but instead, a product rather like paper towels.

And small sawmills for planing lumber and for making products like window sash continued to operate in North Amherst. The Holden Lumber Company, on Montague Road, only closed in 1969, after operating as well-known sash makers for about 70 years. The trade passed down from father to son over the generations and the company was known for their specialized work for homes near Historic Deerfield and for the historic Pelham Town Hall-Church complex, another local historic landmark. Holdens had also made tobacco sash, an old-fashioned term for the delicate lengths of wood on which plants were hung to dry. Holden’s factory was razed and replaced by a gas and service station with the rise of automobiles in the early 20th century.

Puffers Grist Mill and the Canal

A major change took place between the first and the second World Wars. Even though most of the mills had disappeared by this time, the dam at Factory Hollow and much of the land on either side of the Mill River were now owned by the Puffer family. They had also operated an historic grist mill on Montague Road, built in 1838.

From 1844 until 1934, Puffers Grist Mill continued in operation with mill stones that had been imported from France but in all other respects a very local operation. This was possible thanks to a canal constructed along the north side of the Mill River Recreation Area. The water exited “into the downstream river near the Mill River Bridge” although it is easy to miss the bridge today. This industrial site to the west of Cushman, Factory Hollow, and Puffers Pond is fascinating as the Puffer family lived across the street from the Grist Mill that later became a much beloved gift shop. Stephen Puffer (1914-2011) remembers this era in his reminiscences of more recent times, recalling working in his father’s ice works that had been created at the same time as the first World War. The Puffers first built an ice elevator (1912) and then an icehouse (1916); these were located on the southern edge of the shore of Puffers Pond, above the dam that can be seen from Mill Street today (now a one-way street.)

The icehouse site is now a portion of what is called South Beach on Puffers Pond. For nearly half a century, the Puffer family harvested ice and delivered it to families in Amherst. Is there anyone left, reading this column who remembers their grandparents (maybe) having an ice box in which to keep the block cool in the summer months?

The sandy shorelines of both North and South beach at Puffers Pond recall another industrial activity in North Amherst. Not far from the pond is a street called Sand Hill Road that links Mill Street and the Pulpit Hill area to Pine Street and the Cushman neighborhood. Researchers have commented that the glacial hills of sand and gravel deposits in North Amherst are “poor for agriculture” [the accepted cry is “We have rich farmland one side of Route 116 and just rocks the other side!”] Sand dunes take us all the way back to this area’s prehistoric and ancient beginnings when Owen Drive, East Pleasant Street (near North Amherst’s old burial ground) and the UMass Student Farm were the eastern edges of Lake Hitchcock. If we were standing here millennia ago, we could paddle or look west across to an island that is Mount Warner today.

There is still an operating sand and gravel operation on Route 63 just by the Leverett town line and the town-owned site that was the Ruxton Company (on Pulpit Hill Road) which was one of the ‘mouths’ of the Mill River from the same time frame as Lake Hitchcock. The gravel extraction operation had drawn pond water for its businesses. In 1969, the Ruxtons and the Puffer family donated the dam and the pond and the gravel operation site to the town of Amherst.

That decade deserves its own story as it is clear to me now that this part of Amherst had long been a community destination within living memory especially for people who enjoy open space. The scenic value of the Mill River and Puffers Pond, along with the Mill River Recreation Area have been preserved coinciding with a period of “greatly expanded enrollment” at UMass in the early to mid 1960s. Preservation and conservation projects have sought not only to protect water quality but also greenways, sensitive ecological areas and wildlife habitat. The Town of Amherst’s Conservation Department had begun to acquire properties along the Mill River starting in 1961 and by the end of the decade a new vision had been born for the whole of North Amherst.

Read previous Amherst History Month by Month columns here.

Yes, I do remember ice being delivered to my grandparent’s kitchen outside of Philadelphia!

Part 1 of Hetty’s North Amherst series was revelatory because it brought a vanished past to light. This Part 2 touches more recent history but is revelatory in a different way. As developers and builders are currently changing our town’s landscapes to accommodate a more transient population it is important to be reminded that until recently “the book and the plough” (and the forge) co-existed – not always easily – as a town of scholars, workers and farmers, permanent residents with long family histories and a commitment to the Town that was based on that permanence. We are not just losing that character, we are deliberately burying it in the name of density and infill.

I hope Hetty will do a Part 3 of this wonderful series, focusing on North Amherst’s farming past and present and the essential part that families of eastern European origin played in the history of this community.

Echoing my outside-of-Philadelphia compatriot and friend, I too look forward to such a Part 3…!

And I hope it will also touch more in the “micro-geology” of the area, and its implications for agriculture an other land use: one parcel might be a well-drained leveled sand hill with a few feet of loam or loess atop, good for wet-season crops, while heavier or wetter soils might be best for dryer seasons’ crops, cow pastures, hayfields and the like. Accompanying USDA soil maps combined with USGS topographic maps would help tell those stories.

In many places those former farms have “grown their last crop” (at least for the foreseeable future): housing!

But good examples where that’s not happened are the UMass Agricultural Learning Center farm to the east and north of the former Marks Meadow School and Wysocki house; and North Amherst Community Farm (formerly the Dziekanowski farm) a bit further to the north, fronting on both North Pleasant and Pine Streets. Surrounded by housing for thousands of North Amherst residents, these two farms book-end a complex agricultural and silvicultural landscape of a couple hundred acres, threaded by streams and wetlands with riparian and field-bordering forests. And if I’m biking or walking home after dark on the paths and old farm roads there, I might make up and belt out some silly songs, just to let a wandering black bear know I’m also in the neighborhood ;-)!)