Almanac: Looking For Lead

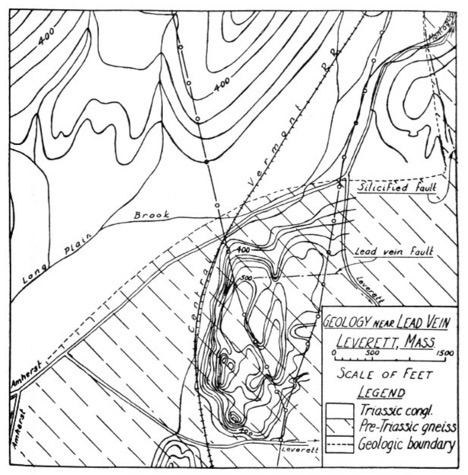

The intriguing 1942 map showing a “lead vein fault” that inspired this week’s column. Photo: Public domain

While researching last week’s column about the Sunderland caves I came across a book about local geology written in 1942 that included a list of “Interesting Places” in the Connecticut river valley. The Sunderland caves were there, as well as Titan’s Piazza, Mt. Sugarloaf, and something that piqued my curiosity: “The Old Lead Mines.” Lead? Here?

The book explained that prior to the American revolution the colonists got lead, which was used for all sorts of applications beyond bullets, from Europe. With the commencement of hostilities and the pressing need for ammunition, the colonists sought the mineral locally. They found veins of lead in four spots on the west side of the Connecticut river and one on the east side, at a location in Leverett. The book included a map purporting to show the location of the lead vein in Leverett, although, as you can see from the image above, the arrow points to a suspiciously straight line leading from what is now Long Hill Road on the east across a hilly area toward the railroad line and power line cuts to the west off of Route 63.

A friend and I spent a pleasant afternoon exploring this surprisingly rugged, forested area last weekend, both on trails and off. Neither of us being geologists we emerged from our meanderings with more questions than answers. For starters, we found three obviously-human-made trenches in the vicinity of the area indicated on the map.

The trenches were roughly 10-15 feet deep and about 25-50 feet long with steep sides. They were clearly old, with sizeable trees in some and bottoms filled in with leaves and debris. But somebody, at some point, was obviously exerting no small amount of effort to find something in the ground, and, given the evidence of the map, it’s likely these were part of the local lead-mining operation.

There is, in fact, a “Lead Mine Road” about a mile south of where we were, although it’s a relatively new road so I suspect the name is just a historical reference, not an indication that the road was actually used to access a mine. But a database of mines in North America identifies, with two adjacent dots, “Lead mines” on the northern side of the area we were exploring. There is nothing, now, to suggest the mines were where the dots are, but it’s possible that the dots just indicate old entrances to roads that used to lead up the hill to the area where we found the trenches. (Linguistic aside: “lead” is one of those diabolical words in English that have two meanings and two pronunciations that can only be inferred by the context in which they occur. How people learn this crazy language is beyond me.)

Interestingly, adjacent to one of the trenches we found a pile of split rocks and rock shards that looked very fresh. Somebody had recently been smashing large rocks apart, looking for something…but what? Possibly some of the minerals often found in the vicinity of lead veins, such as galena, which is a crystallized form of lead ore that can be quite pretty. I’ve come across similar signs of active rockhounding in the vicinity of Mt. Orient and I’ve been told by friends who indulge this pastime that those sites were made by people looking for amethyst crystals (which is where Amethyst Brook gets its name).

In exploring further we found no other obvious signs of an old mine, but we did find some pretty minerals, including a piece of quartz studded with large flakes of mica, and a vein of what seemed to be faceted marble, although it was probably some kind of quartz (any geologists in the house? Help!).

This little adventure in search of old lead has rekindled an interest in learning more about the minerals and crystals to be found in this area. I associate New England with granite and other boring rocks like schist and gneiss and shale. But evidently there are not only beautiful crystals and minerals to be found around here, but also gold in them thar hills. Just goes to show you that almost always there’s more to nature than meets the eye!

Almanac is a regular Indy column of observations, musings, and occasional harangues related to the woods, waters, mountains, and skies of the Pioneer Valley. Please feel free to comment on posts and add your own experiences or observations.

SB wrote: …roads that used to lead up the hill to the area where we found the trenches. (Linguistic aside: “lead” is one of those diabolical words in English that have two meanings and two pronunciations that can only be inferred by the context in which they occur. How people learn this crazy language is beyond me.)

I paused to do a double-take at the “first diabolical instance” and then laughed out loud as I reached SB’s parenthetical comment. One way around SB’s predicament might have been to rephrase “roads that used to lead” with “roads that once led” (but then SB would need to comment on why the past tense verb “led” rhymes with the metal “lead” instead).

And one nuclear-physical comment that may help inform SB’s geological queries: lead (or more precisely, the stable lead nucleus, Pb-208) is the end of the Thorium-232 series for radioactive decay, as well as the ends of both the U-238 and U-235 Uranium series (the former is also known as the Radium series, and the latter as the Actinide series); there’s a fourth – the Neptunium-239 series – that also passes through a relatively stable isotope of uranium (U-233) before decaying to an isotope of bismuth (Bi-209), which almost stable (its half-life is more than 100 times more than the age of the known universe) but will eventually end with thallium (Tl-205).

For those who want to take an even deeper dive, please see

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decay_chain

There’s more than just gold (or lead) in them thar’ hills – indeed, almost all that granite is (mildly) radioactive – so you should also find the various precursors to lead (and bismuth and thallium up thar’ too), many which are alpha emitters: avoid inhaling the dust if you decide to pulverize the rocks; and if you have a house up thar’ then be sure to ventilate its basement or crawlspace, since radon (a gas, with several alpha-emitting isotopes, that you do not want to inhale much for long) is almost surely seeping in….

And, hey, now it’s Hallowe’en 😉

P.S. My eyes were too tired at the midnight hour to read the exponent on the power of 10 for the half-life of Bi-209: it’s a lot more than 100 times longer, than the age of the known universe – it’s more than 1,000,000,000 times longer! – so when “looking for lead” in them thar’ hills, expect to “see some bismuth” too.

Maybe the next time SB hikes in Leverett, he can take with him a portable radiation detector? Though it’s hard to “see” the alpha-particles directly, they can be “seen” indirectly with one of these

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geiger_counter

and from that one might be able to infer their source nuclei.

On the other hand, maybe such “truths” are better left buried?!

Oh, yes … it’s Hallowe’en indeed!!! ? ? ?

P.P.S. Even a recent PNAS article

https://www.pnas.org/content/116/27/13255

on novel “topological crystalline insulator” aspects of bismuth pinched (or perhaps provided?) some text for

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bismuth

which reminded me (in case all that nuclear physics – or local politics – caused indigestion) that bismuth subsalicylate is the active component of Pepto-Bismol! ? ? ? ? ? ?

Lead mines in Hatfield right behind the Mobile Home Park (short ways in the woods North end, rear) on 5 and 10 are long flooded Tunnels that can be navigated by rubber raft. Still a lot of lead crystals too be found near the opening. Narrow shaft towards the top back of the pit leads down to the flooded tunnels.