Almanac: Of Potholes And Giant’s Kettles

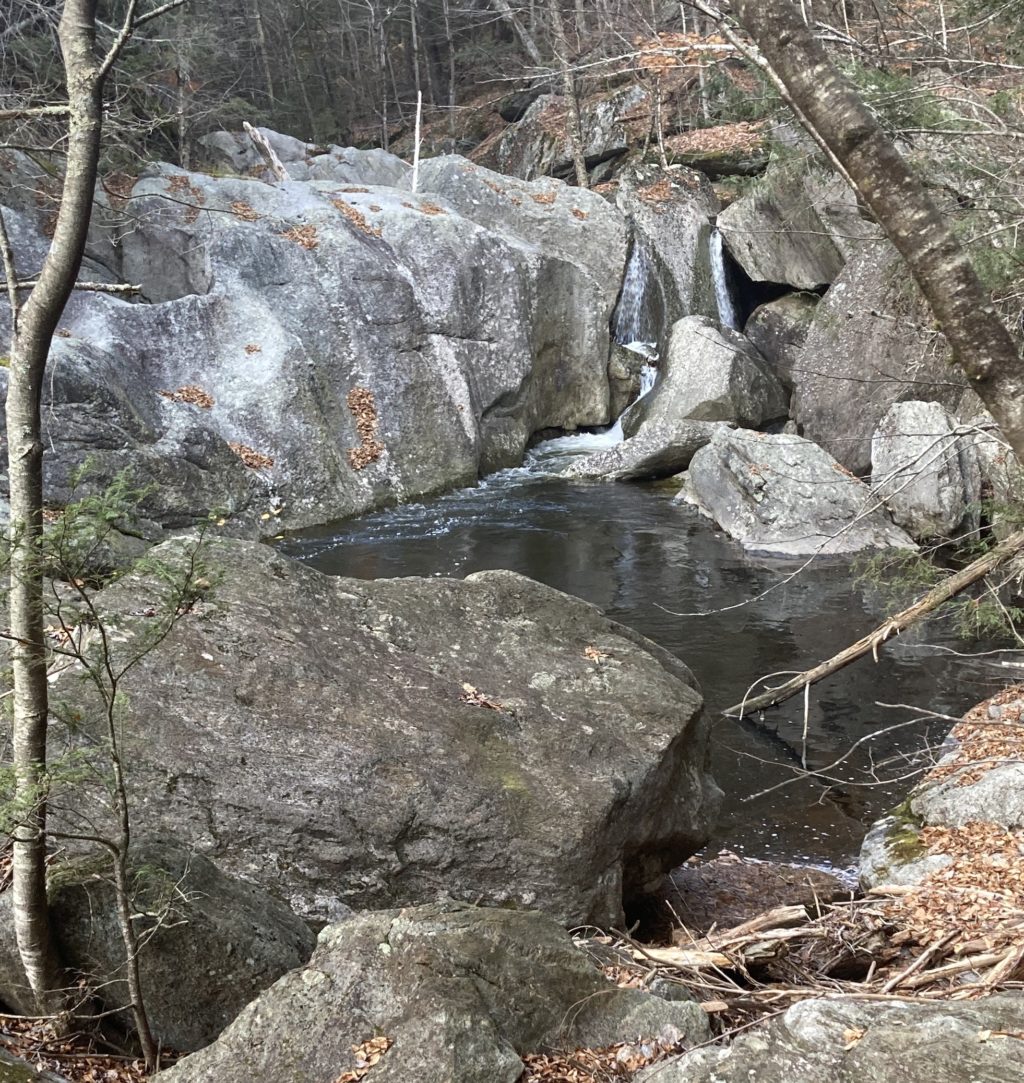

Rocky glen on the Little River outside of Westfield. Photo: Stephen Braun.

A couple of weeks ago I found myself in the middle of a thicket of mountain laurel with no sign of the abandoned trail I had been trying to follow. I wasn’t lost, exactly—I was heading steeply down into a ravine, at the bottom of which was the Little River and what I had been promised was some “really cool” geology. As long as I didn’t hit an unexpected cliff, I felt reasonably certain I would make it down. The fact that I’d never been there before and that the sun was sinking fast caused a flicker of concern—but my curiosity about this place was much stronger than my common sense…which is a somewhat distressingly common pattern in my life.

Before long, as I bushwhacked downwards, I discovered why the trail had been closed by the good people who run the Nobel View outdoor center in the hills outside of Westfield: it’s very steep, slippery, rocky, and devoid of good hand-holds. Not impossibly steep, just a tad dangerously steep. After a drop of about 600 feet and a final slide-on-the-butt down a large angled slab of rock, I emerged into the perfectly lovely spot pictured above. The Little River plunges over and around massive rocks, alternating between a narrow, rushing torrent and wide, quiet pools.

I’d been told that there were potholes in this stretch of the river. Potholes, also known as “giant’s kettles,” are deep, often nearly cylindrical holes carved into solid rock and ranging in size from a few inches to many feet in diameter. Although they are sometimes called “glacial potholes” they actually have nothing to do with the glaciers that retreated from these parts about 15,000 years ago. Potholes form whenever enough water flows rapidly for enough time over the right kind of fine-grained bedrock.

A positive feedback loop occurs whereby an initially shallow dip or divot in the bedrock gets scoured by sand and rocks carried by the water. The grinding deepens the hole and the hole then traps larger pebbles or rocks, which become “grinders” that accelerate the boring action. The resulting shafts can be impressively circular and deep, although they come in all shapes and sizes.

I’ve seen potholes—and sometimes dunked into them—on many rivers and streams in this area. As retired Greenfield Community College geology professor Richard Little said, in an interview with the Greenfield recorder, “You could say that potholes are as common in our rivers as they are in our roadways.”

The most well-known collection of potholes are on the Deerfield River in Shelburne Falls. Not only are the potholes there numerous, they are bored into some exceptionally pretty, striped metamorphic rock called felsic and mafic gneisses.

In a global database of 3930 potholes from 33 locations, Shelburne Falls ranked as the 7th-most abundant of the locations included in the survey, with 154 potholes counted.

As I clambered over and around the big rocks in the Little River, I saw, on the opposite bank, what looked like a really big pothole. Getting to it, however, required yet more questionable decision-making about leaping between rocks at the bottom of which was very cold, rushing water. But, hoping I still had at least one of my nine lives to use up, I went for it, and before long was standing next to the biggest, baddest pothole I’ve ever seen. It was irregular in shape, and dry at the bottom, but large enough, and deep enough, to hold half a dozen people with ease.

Potholes usually enlarge, with enough time and scouring, and sometimes two initially separate potholes will merge into a larger pothole. The hourglass shape of this pothole likely resulted from the erosion of two adjacent potholes at a time when the river was flowing over this side of the gorge. A friend of mine took the shot below of a pair of potholes on the west branch of the Mill River near Williamsburg that illustrates an earlier stage of pothole merging. You can see the slowly-eroding wall between them as well as the “grinders” at the bottom of the right-hand hole.

I didn’t tarry long at the lip of the big pothole since the light was fading, it was getting cold, and I still had to re-cross the river by dicey rock-hopping. But I paused long enough for a few moments with the scene, the river protesting its twisting passage between the giant boulders in a gurgling, rushing tongue, and the air smelling clean and cool as gin, carrying more than a hint of winter.

Almanac is a regular Indy column of observations, musings, and occasional harangues related to the woods, waters, mountains, and skies of the Pioneer Valley. Please feel free to comment on posts and add your own experiences or observations.