Library Project Failures Expose Cracks In State Grant Program

Photo: https://www.joneslibrary.org/

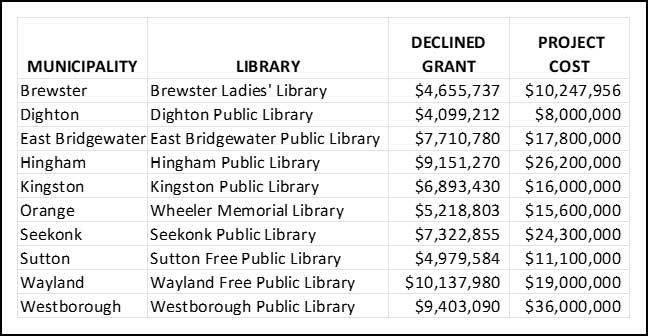

10 Out Of 33 Communities Receiving Recent Library Construction Grants Have Withdrawn

Lauren Stara of the Massachusetts Board of Library Commissioners (MBLC) reports in a recent blog post that after six years, the state’s Public Library Construction Program (MPLCP) has worked its way through the waiting list of cities and towns awarded funding in the board’s 2016-2017 Grant Round. Of the 33 library projects receiving grants, 10 have turned back their grant awards. This withdrawal rate is in line with the historical 25-30% of municipalities declining grants over the 35 years that the MPLCP has existed, reports Stara.

Out of the 33 grant-funded projects, 13 have been completed, while 10 are currently awaiting local funding approval, in final planning, or under construction. With inflation remaining a concern, some of these unfinished projects, such as Amherst’s Jones Library renovation-expansion, still face funding issues and an uncertain future.

Rising Costs And Lack Of Local Approval Frequently Cited

The 10 communities that have withdrawn from the program turned down a total of $69.6 million in state grant money. Reasons reported in the media for withdrawing ranged from skyrocketing construction costs after the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020, to Town Meeting or City Council rejection of the required borrowing authorization, to competing local funding priorities.

Hingham gave up a $9.2 million award after seeing its total library project cost estimate rise from $26.2 million to $30 million. Select Board Chair Paul Healey was quoted as saying “I’m deeply troubled by what’s happening here because this is a proposal that is rolling out in the face of a number of other pressing needs that the town is facing.” He cited the need to renovate the local Foster School and fire station.

In Sutton, advocates for a new library to replace its existing 2000 sq. ft. facility faced stiff opposition to the $11.1 million project from townspeople concerned with the tax ramifications after recent borrowings for a new police station and school. The MBLC’s Stara defended the project, reported the Worcester Telegram, saying, “Libraries are no longer warehouses for books. They’re becoming de facto community centers in many, many places.” Sutton Town Meeting voted against funding the library plan, walking away from a $5 million state grant.

Last November the town of Orange voted down a debt exclusion override needed to support borrowing $10.4 million to update the Wheeler Memorial Library, which has not been renovated since it was built in 1914. In doing so the town gave up a $5.2 million MBLC grant. Undeterred, Orange library trustees plan to repurpose $490,000 previously raised for the project, and are seeking a new grant from the MBLC’s recently announced 2023-2024 library construction grant round.

The Massachusetts Public Library Construction Program Shows Room For Improvement

Applying for a state library construction grant often begins with the local library director, trustees and fundraisers who may hunger for lofty building improvements and additional programming space but can be less attuned to the broader financial needs of the community.

For its part, the Massachusetts Board of Library Commissioners encourages expansive and expensive library makeovers. For security and ease of staffing, the MBLC reportedly favors “long sight lines” which can mean knocking down walls and removing stacks.

Even more costly is the trend among librarians, vigorously pushed by the MBLC, to recreate libraries as community spaces. This movement is driven partly by technological changes as reading materials are more often being delivered digitally, reducing the need for patrons to visit their local library. Facing declining attendance and a threat to future relevancy, library professionals see a need to reinvent the public library as a community resource that presents entertaining and educational programming, and may serve as a “library of things” that lends anything from musical instruments to kayaks.

This vision may make sense for communities with seriously antiquated and undersized libraries, a scarcity of public meeting space, and that have a surplus of funds to meet the MBLC’s matching grant requirements. But as grant withdrawal statistics show, this profile by no means fits all Massachusetts cities and towns.

Exacerbating the situation is the length of time it takes for a library project to go from grant application to, if successful, completing design, bidding and construction. As Amherst residents have seen, this process can take seven years or more, and can be accompanied by substantial cost increases. The MBLC has recently attempted to streamline the process by eliminating a separate planning and design phase application, but a library construction project can still span years.

See related How Can It Take 15 Years and $32 Million to Build a Neighborhood Library? (New York)

too often library building committees find themselves stuck between a rock and a hard place. Either sacrifice hundreds of hours of work soliciting non-fungible donations and landing a multi-million-dollar library construction grant, or persist in throwing library and municipal budget dollars that are urgently needed for other purposes into the library project money pit.

MBLC regulations prohibit library construction grant money from being used for building maintenance, nor will they allow a proposed building’s size, once accepted, to be changed. So, too often library building committees find themselves stuck between a rock and a hard place. Either sacrifice hundreds of hours of work soliciting non-fungible donations and landing a multi-million-dollar library construction grant, or persist in throwing library and municipal budget dollars that are urgently needed for other purposes into the library project money pit.

When library and municipal leaders make the decision to stay the course with an over-budget building project, they may be induced by persuasive (and often wealthy) advocates to continue throwing good money after bad. Moreover, significant compromises may be made to bring project costs down to earth.

Sustainability improvements, high quality materials and modern furnishings may be put on the chopping block through a process known euphemistically as “value engineering.” However, due to MBLC regulations, the obvious solution of cutting costs by scaling back the library project’s size and scope is not allowed.

The MBLC has a clear interest in seeing its subsidized construction projects built. Stara and co-administrator of the MBLC construction grant program, Andrea Bono-Bunker, have hosted a podcast episode called Advocacy Stories: Opponents that advises library project supporters on overcoming community opposition and “getting ahead of the naysayers.”

The MBLC therefore may take a hands-off approach to enforcing the letter of the law spelled out in its regulations. Observers of Amherst’s currently $10-million-over-budget Jones Library renovation-expansion have seen a willingness by the Library Building Committee to skirt requirements to report impacts to a property listed on the State Register of Historic Places “as early as possible”; to comply with current energy code requirements; and to hire an independent commissioning agent during the project’s Design Phase.

If the MBLC, which has awarded Amherst the largest of its 33 2016-2017 construction grants, has objected to these rule violations, the commissioners have not done so in public.

After library “story time” comes library “question time”….

Given the amount of public funding involved, and what Jeff has just reported, specifically that the MBLC and its staff

• take[s] a hands-off approach to enforcing the letter of the law spelled out in its regulations.

• advises library project supporters on overcoming community opposition and “getting ahead of the naysayers.”

• skirt[s] requirements to report impacts to a property listed on the State Register of Historic Places “as early as possible”

• [fails] to comply with current energy code requirements; and

• [neglects] to hire an independent commissioning agent during the project’s Design Phase.

is it reasonable to ask whether the MBLC — and possibly its cooperating grantees — may fit the profile of a “corrupt organization”?