OPINION: THE THREE PURPOSES OF SCHOOLING (1990)

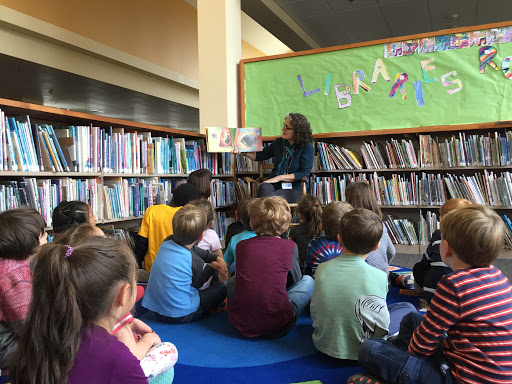

Elementary school class in school library in Amherst. Photo: arps.org

Note: As the community and the schools consider how, if and when to re-open our schools in 2020, I thought I would republish this commentary which first appeared in the Amherst Bulletin in 1990. Perhaps it suggests questions that are more pertinent now than even then. In my next Indy piece I plan to consider those questions in light of the challenges and the opportunities that we face while trying to teach amidst a pandemic

There is an inexpensive way of improving schools: thinking about them differently. Right now, most people see our schools as educational institutions. They are, but that is only one of three broad sets of purposes that communities hold for their schools. First, they want schools to take care of their children for a specified number of hours each day and a specified number of days each year. They want the schools to act in loco parentis and they want them to assure that our children are safe and that our children behave. Some writers, in commenting about this purpose, talk about control, with its overtone of coercion. There is good reason for this talk and some important insights to be gained from it, but here let us not engage in the controversies it inspires. Rather, let us settle for what almost everyone can agree to – that the schools have a custodial function and that most people want them to.

Second, most people want schools to let us know how children are doing. They want measurements that are reliable and they want tangible evidence that children are or are not successful. In fact, what they really want to know is whether their children are more or less successful than other children. Testing, grading and grouping are three common methods that schools use to respond to this expectation. Many argue that these are mechanisms of control and oppression, and again there is much to be learned from these arguments, but it is not necessary to agree with them to agree that the schools have an accounting and sorting function and that most people want them to.

Third, most people want children to learn interesting, important and useful things. They usually couch these expectations in terms of knowledge and skills, and particularly knowledge and skills that will enable students to become functional and reliable citizens and parents. Critics of schools charge that the mainstream curriculum has an inaccurate, incomplete and self-serving sense of what knowledge and skills students need. Still, almost everyone agrees that schools serve an educational function, and most people want them to.

Most commentators do not really acknowledge the first two functions; those that do generally believe them to be in the service of the educational function. But the custodial, accounting/sorting, and educational functions do not really fit together; they interfere with and undermine each other. Many of the educational and organizational practices that typify American schools are based upon assumptions that the three functions are tightly connected, but if people step outside these assumptions, the questions come readily enough.

Why assume that all students, regardless of age, ability or interests should be in school for about seven or eight hours a day, 180 days a year.

Why assume that grouping children in classrooms with a roughly 25 to 1 student-teacher ratio is the appropriate mode of instruction for almost all of them?

Assumptions like these are based upon the schools’ custodial function. They cannot be defended educationally even though they ordinarily are. Arguments for a longer school day are not based upon what we know about how people learn. The grouping of twenty or more students in a classroom for seven or eight fifty-minute periods every day is a dubious educational practice although an effective means of control.

Sorting practices are also deeply embedded in schooling. They are usually considered to be educational but they are not. For example, student progress is most often measured by testing which is external to the activities from which learning is accomplished. Tests trivialize understanding and are destructive of learning. Student progress is most often reported by marks which are highly generalized and do not reflect the complexity, the subtlety and the individuality of learning. These marks become the permanent record of the student’s academic accomplishments and remain highly influential long after their basis is discarded and forgotten. Students are grouped together for instruction according to several criteria, among which frequently are measures of intelligence, accomplishment and aptitude. Such groupings limit opportunities for students to study certain subjects, attain certain places in class rankings and achieve distinguished records.

All of these practices have their strong defenders, but while I am not among them my purpose here is to emphasize that they are not educational practices and that they may be defended, if at all, as accounting and sorting mechanisms.

It would be helpful for communities to clear away the custodial and accounting functions and see what is left. It would be a surprise. Indeed, we know so little about how people learn that once we have cleared away the custodial and accounting/sorting functions very few assumptions fit squarely into the educational domain. Perhaps my main purpose in writing this piece is to focus our attention on the educational domain and begin to acknowledge its mysteries.

Michael Greenebaum was principal of Mark’s Meadow School from 1970-1991 and from 1974 taught Organization Studies in the Higher Education Center at the UMass School of Education. He served in Town Meeting from 1992, was on the first Charter Commission in 1993 and served on several town committees, including Town Commercial Relations Committee and the Long Range Planning Committee.