Almanac: Strange Pearls

Eastern crayfish (Cambarus bartoni) are very common in our local streams and ponds. Hidden inside these mini-lobsters are surprising structures that can be found in an unusual place. Photo: Creative Commons

The woods, fields, and waterways of the Pioneer Valley are rich with wildlife. Over the years I’ve seen moose, bears, beavers, deer, foxes, a bobcat, a fisher, otters, groundhogs, porcupines, owls, and eagles to name a few. But such sightings are, at least for me, mighty rare. On most hikes I only see the usual suspects: squirrels, chipmunks, and common birds such as crows, chickadees, and blue jays. That’s because moving humans tend to be pretty noisy—even a solo hiker who isn’t talking usually makes sounds that are very audible to animals, which scram long before we see them.

But if the animals themselves are difficult to spot, the signs they leave behind are often not…at least for a trained eye. Scat, in particular, offer a wealth of information, not only about what critters have been visiting an area, but what they’ve been eating. I’m a beginner scatologist, but I had the good fortune the other week of being on a hike with a group of nature lovers that included Pam Landry, Wildlife Education Coordinator for the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife. Pam knows her scat, and we found signs of moose, fox (or coyote), bobcat, otter, and even beaver (more about that one in a later column).

We were bushwhacking in a forest on the eastern side of the Quabbin reservoir, along a stream and, then, a large wetland area. We found a great deal of otter scat, which consisted of a crumbly mix of fish bones and the crunched up shells of crayfish. It wasn’t stinky and was easy to break apart for a closer look at what the otters had been eating.

It was during one of these little explorations that Pam found something I’d never even heard of before, much less seen: a gastrolith. It looked like half of a small white pea and was as dense as a tooth. “Gastrolith” is derived from the Latin for “stomach stone.” Some birds purposely ingest pebbles or small stones as aides to digestion, and these are one kind of gastrolith. But the kind we found are not actually stones, they are stone-like structures made by crayfish.

Like all invertebrates, crayfish have exoskeletons. These armor-like structures prevent growth and, therefore, have to be repeatedly shed during molts to allow the animal to develop. A challenge with this form of maturation is that the exoskeletons require a lot of calcium for their construction, and, especially for freshwater invertebrates, calcium is somewhat scarce. Crayfish (and lobsters as well) have developed a beautiful adaptation for dealing with this situation: before a molt, they extract much of the calcium from their existing exoskeleton and store it in the form of gastroliths that are attached to the lining of the stomach. The gastroliths grow, like pearls, until a molt, at which time they dissolve, releasing the calcium for use in building the new exoskeleton.

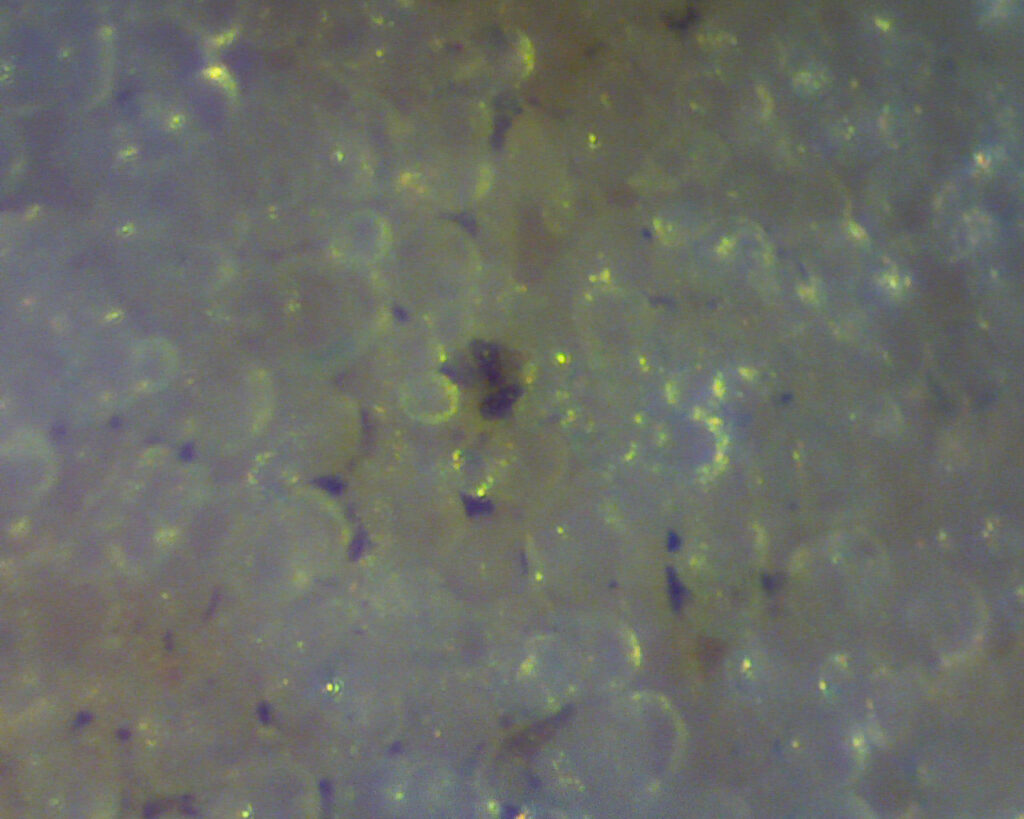

With the zeal of a treasure hunter, I started searching for more gastroliths whenever we came upon more otter scat, finding several. At home I put them under the microscope and could see that the smooth rounded outer layers were composed of extremely small spheres of calcium carbonate.

I’m not sure why finding gastroliths in otter poop makes me happy. Maybe it’s the metaphor…sort of like the lotus growing out of the muck or something. All I know is that it’s fun to discover new things in nature. Sharing those discoveries with you, gentle reader, is icing on the cake.

Almanac is a regular Indy column of observations, musings, and occasional harangues related to the woods, waters, mountains, and skies of the Pioneer Valley. Please feel free to comment on posts and add your own experiences or observations.