What’s Law Got to Do With It? How Amherst’s Disregard of Historic Preservation Law Has Already Forfeited $1,800,000 and Jeopardizes Millions More in Federal Grants

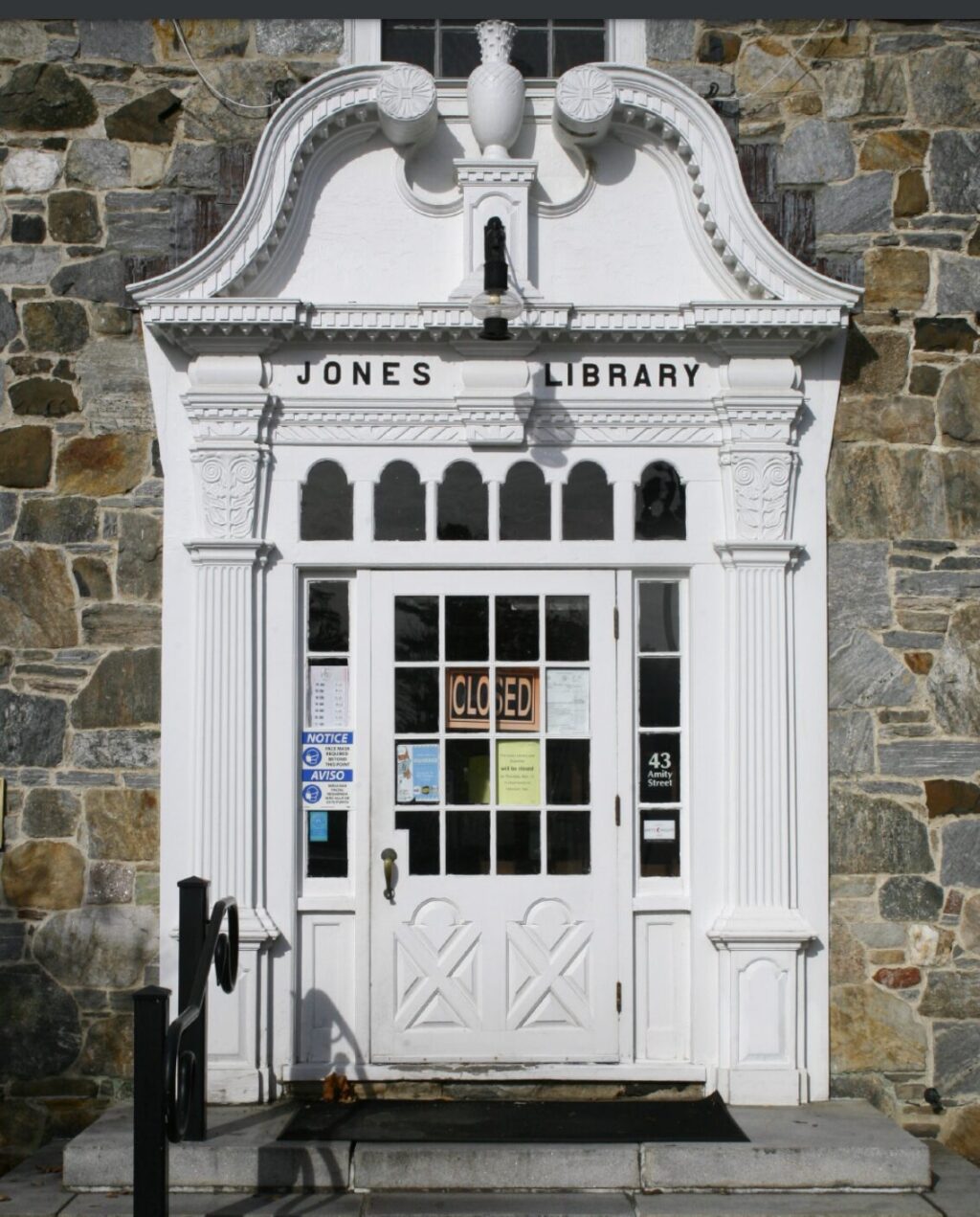

Main entrance to Jones Library highlighting the original historic stonework favored by founding benefactor Samuel Minot Jones. Photo: amherstma.gov

A Bit of History

When I retired back to Massachusetts in 1999, one of my first conversations with an Amherst resident started like this: “Have you seen our Jones Library?” The woman’s voice said that the Jones Library was something special. My answer was nonetheless “No.” But over my 22 years in Amherst, I came to appreciate how special the historic Jones Library is, and how it weaves through Amherst’s stories.

It’s well known that a bequest from Amherst-bred Samuel Minot Jones financed the library’s construction and, for several decades, its operations. Jones had a lumberyard on the banks of the Chicago River. In 1871, Chicago’s Great Fire swept greedily toward it. Three days and three nights he and his staff desperately pumped Chicago River water over the lumberyard’s inventory. When the smoke cleared, Jones still had a lumber business — and everyone needed lumber.

Another Amherst native, no longer with us, told me of seeing the stones for the library’s masonry, from an old Pelham stone wall, dragged down Main Street on a stone boat in the 1920s to the library’s future location on Amity Street. Townspeople also contributed stones from their worldwide travels.

Jones had been determined that the girls and boys of Amherst have a public library that was fireproof! The previous library, which was said to be located in a hotel located at what is now the corner of Amity and South Pleasant Streets and currently occupied by the Bank of America was apparently destroyed in a fire. The founding trustees also ensured that the library welcomed children. Its child-proportioned Children’s Library, with its very own front entrance, was apparently a first for North America.

Robert Frost did some of his writing in one of the writers’ rooms on the library’s third floor. He stepped through the library’s iconic, Connecticut Valley split-pedimented main entrance and walked into the elegant office of founding Jones Library Director Charles Greene, to hand Greene copies of his first editions. Frost called Greene “his first serious collector.” There is good reason that the historic library has been designated a National Literary Landmark!

So I have found it troubling in the extreme to observe how much lip service the current Amherst town manager, the current library director, and the current library trustees have given to the Jones Library’s historic preservation, yet how persistently they have violated, and continue to violate, the state and federal Historic Preservation Law that is intended to protect the library’s historic values.

It is troubling, also, that the town and trustees have thereby forfeited $1,800,000 in state-related funding, and have jeopardized some $16,000,000 in state and federal grant funding. They’ve been counting on this to pay toward their demolition/expansion “rehabilitation” project’s ever-rising cost.

Multiple Violations of Preservation Law

These historic preservation laws come into play if state or federal funding, respectively, will pay part of the cost of a project affecting a property listed on the Massachusetts State or the National Register of Historic Places. The 1928 Jones Library is listed on both. Accordingly, violating state or federal law jeopardizes related funding.

The state and federal historic preservation laws differ in details but not in essentials. At the heart of each are “adverse effects” on a historic property that is listed on the State or National Register, respectively.

The federal regulations provide additional guidance via the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties (Secretary’s Standards) (see also here) and their 10 Standards each for four different types of treatment: Preservation, Rehabilitation, Restoration, and Reconstruction. 36 CFR § 68.1.

What’s important here is that any

“Alteration of a property … that is not consistent with the Secretary’s standards”is an “adverse effect.” 36 CFR § 800.5 (2)(ii).

The town’s and trustees’ disregard of the applicable law showed up first in 2015. This was in connection with their Planning & Design Grant from the Massachusetts Board of Library Commissioners (MBLC). The MBLC regulations for these grants required the town and trustees to comply with all legal and regulatory requirements of the Massachusetts Historical Commission (MHC),

“including that which affords the Massachusetts Historical Commission the opportunity to review and comment as early as possible in the planning stages of the project.”

605 CMR 6.05 (2)(c)14.

From an array of proposed building designs, the trustees chose one, from Finegold Alexander Architects of Boston. However, they never gave the MHC the “opportunity to review and comment” on it. The MBLC evidently did not object.

Then, to apply for an MBLC construction grant, the town and trustees had to file a Project Notification Form (PNF) with the MHC. They did so. Their 10/31/2016 PNF was laconic in the extreme. As to their proposed demolition, it noted that the entire 1993 addition would be razed, and said merely:

“There will be selective demolition of the original 1928 structure for the required new work to comply with current building code, ADA, life safety, and programming requirements.” (see page 333 of 526 of the grant application).

This unspecific PNF waved a red flag at the MHC — what was meant by “selective demolition of the original 1928 structure”? And to indicate the nature of the library’s “rehabilitation,” the town and trustees’ PNF said only:

“The original 1928 structure will be rehabilitated to comply with current building code, accessibility, life safety, and programming requirements.” (Ibid.)

The purpose of the PNF was to allow the MHC to determine whether the project would have adverse effects on the historical library or any other Massachusetts State Historic Register property. If the MHC determined that the project would have such “adverse effects,” the MHC would enter into a brisk historical preservation consultation with the town, trustees, Amherst Historical Commission (AHC), and the Amherst public to “eliminate, minimize, or mitigate” those adverse effects.

At about this same time, Jones Library patrons formed the Save Our Library Committee and informed the MHC of ways in which the project appeared to violate the MHC regulations for “Protection of properties included in the State Register of Historic Places,” 950 CMR 71.00.

The MHC’s response to this and to the PNF was a letter sent in late December 2016, and addressed to Amherst Town Manager Paul Bockelman with courtesy copies to Jones Library Director Sharon Sharry, the MBLC, the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the Amherst Historical Commission, Save Our Library, myself, and others. Besides telling Town Manager Bockelman that the library was on the State and National Registers of Historic Places, the MHC explained:

At this time, the MHC is unable to determine what effect the proposed project will have on the historic property …. The MHC requires complete photographic coverage of proposed work locations on the exterior and the interior of the library, keyed to sketch maps or floor plans. Please provide a detailed project description along with an indication of what exterior and interior sections of the building will be removed and whether they will be stored for future use….”

At the time, the project had only to comply with Massachusetts Historic Preservation Law. Nonetheless, the letter also noted presciently that its

“comments are offered to assist in compliance with Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended….”

In other words, if the town provided project data to comply with Massachusetts historic preservation law, this would likewise help to comply with the federal historic preservation law, if this ever became relevant. But it is fair to say that the town manager and library director blew this regulatory requirement off completely, as well. They never replied. They never supplied the MHC with the requisite data.

Furthermore, less than a month after this 12/23/2016 MHC letter, the town manager, library director, and all the library trustees signed their application for a $13,633,166.00 MBLC construction grant. They represented, wrongly, that the library was NOT on either the State or National Registers of Historic Places.

Nevertheless, at various times over the next several years the library director said publicly, and various trustees also said publicly, that they were going to comply with the MHC’s requirements.

But for years, they submitted nothing. As a result, they never engaged with the MHC to complete the subsequent steps in its mandatory preservation consultation process, and they never entered into a written agreement to make the necessary changes in the project’s designs.

It Seemed for Years as If They’d Get Away With It

It seemed for years as if they’d get away with it. Although Save Our Library informed the MBLC of the 1928 library’s historic status, others observed that neither the MBLC staff nor the library commissioners themselves seemed to care that this project violated the applicable law. This became unmistakable when the MBLC released to the town, in December 2021, the first 20% tranche — $2,774,263 — of its construction grant.

The town even sent the project out to bid in January 2024. They rejected the single bid they received (see also here)— for some $6.5 million above the estimated cost. So now the town and trustees have made surface-level “value engineering” changes to the building’s design, in the hopes that a second round of bidding will bring the job in for less. They plan to put the project out to bid again this month..

Nonetheless, the Town’s blatant, many-years’ violation of 950 CMR 71.11, “Failure to Inform the Massachusetts Historical Commission,” evidently means that it must halt the project. This regulation provides:

“Should a state body … fail

* to notify the MHC about a project,

* to provide the MHC with the information necessary to determine whether the project will adversely affect a State Register property,

* to identify and assess alternatives to the project,

* to meet with the MHC to discuss alternatives, or

* to respond in detail to the MHC’s Statement of Prudent or Feasible Alternatives, or proposed Joint Memorandum of Prudent and Feasible Alternatives,

then the state body shall not proceed with the project … until the MHC states that such failure has not frustrated the purpose of M.G.L. c. 9, §§ 26 through 27C.”

The town appears to be a “state body,” that is, “any … authority of the Commonwealth established to serve a public purpose.” 950 CMR 71.03. So it seems accordingly that this regulation applies here, and that thus the Town “shall not proceed with the project.”

As discussed above, the town and trustees have never engaged in the third through fifth steps in the state’s mandatory historic preservation consultation process. Nevertheless, as mentioned, they proceeded and are continuing to proceed with this project.

But they’ve run into trouble indirectly with the federal Historic Preservation Law. Since 2017, the trustees have been planning to raise some $1,800,000 for the project by selling what are called “Massachusetts Historic Rehabilitation Tax Credits” (tax credits). This $1.8 million has been included in all the trustees’ presentations, to Town Council and others, about funding for the project.

For these tax credits, the MHC certifies that a project’s designs, for a historic property owned by a non-profit, meet the Secretary of the Interior’s “Rehabilitation” Standards. Then, if the MHC finds the completed project satisfactory, the property’s owner can sell these tx Credits to a for-profit buyer that wants to reduce its Massachusetts tax liability.

In 2023 therefore, the town and trustees submitted to the MHC additional PNFs with updated project designs and additional materials. This PNF seems to have been for the federal grants mentioned below. But it apparently did double duty as to the tax credits. These materials included the Historic Structure Report on the library, and a Report by Epsilon Associates that recommended a finding of no “adverse effect.”

The MHC’s denial of tax credits dated 12/29/2023 must have come as a severe shock to the library director and to any trustee with whom she shared the denial letter. This informed the library director that the MHC

“is unable to … allocate credit to your project … because the proposed project …. violates [the Secretary of the Interior’s] Standards 2, 5, 6, 9, and 10.”

MHC 12/29/2023 Letter, at 1.

Yet this discouraging letter ended on an upbeat note:

“We encourage you to reapply in the next application cycle if the project can be redesigned to meet the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation.

Ibid., at 2 [italics in original; bold font supplied].

Town Never Redesigned the Project to Meet Secretary’s Historical Rehabilitation Standards

The town never redesigned the project to meet these Secretary’s Standards. Nonetheless the library director evidently reapplied for the tax credits.

And nearly four months later, the MHC again denied tax credits for the project, noting that some of the library director’s responses to the MHC’s initial comments

“directly state that … portions of the proposed project scope are based on response to Massachusetts Board of Library Commissioners (MBLC) requirements.”

These “MBLC requirements” presumably pertain to the project’s interior: the MBLC would have scant concern, if any, with the project’s exterior. Crucially, review under the Secretary’s Standards “extends to the entire interior of a building….”

In its second denial letter, the MHC explained its decision in more detail, based on project changes to the 1928 library’s interior:

“[F]loor plan modifications will be made, causing the removal and loss of historic fabric. The reconfiguration of the historic 1928 building circulation patterns and the removal and loss of historic fabric does not meet the Standards (Standards 2 and 5.)

That “removal and loss of historic fabric,” which fails to meet the Secretary’s Standards, appears also to qualify as an “adverse effect” on a historic property, as defined in both the MHC regulations and the federal regulations.

This second MHC letter made the denial final. The town would never receive that $1,800,000 in tax credits to help fund the project. This is a lot of funding.

Another complication, resulting from the town’s and trustees’ refusal to provide the MHC with required data on the project, and to redesign the project accordingly, came with the two federal grants, totaling $2,100,000, which the project received last year from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH).

Briefly, HUD requires the town to complete an environmental review before putting the project out to bid (in this case, out for a re-bid). This environmental review, in turn, requires the project to comply with the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended. Long story short, to qualify for these federal grants, the town and trustees can no longer avoid redesigning the project to comply with the federal Historic Preservation Law.

Before putting this project out for re-bid, therefore, this will mean redesigning the project to eliminate its violations of the Secretary of the Interior’s Rehabilitation Standards. Though it seems scarcely possible to redesign this project and have the designs redrawn in less than a month, that is presumably the purpose of the Section 106 historical preservation review process that the Town announced last month.

Furthermore, in federal historic preservation matters, MHC Executive Director Brona Simon wears a second hat, as the State Historical Preservation Officer (SHPO). Given the MHC’s finding that the project violates five of the Secretary’s 10 Rehabilitation Standards, how likely is she to accept this project, as presently designed, for Section 106 purposes?

In addition, even if the town’s Section 106 process nonetheless approves the project as it is now, the town does not have the last word. The NEH must determine that the project meets the Secretary’s Standards. We know that from the MHC. In a 11/22/2023 letter to the NEH, SHPO Brona Simon stated unequivocally:

“Ultimately, under Section 106 [of the National Historic Preservation Act], NEH must make a determination of effect and complete the [historical] review process.”

A long-time Jones Library supporter asks: If, instead of redesigning the project to meet the Secretary’s Standards, the town simply decides to forgo the two federal grants, what results?

The town presumably still wants the approximately $11,000,000 balance of its MBLC construction grant. Foregoing the federal grants would then seem to throw the town back on the MBLC regulation cited above: that it “shall not proceed with the project” unless, and until, it 1) consults with the MHC, the AHC, and the Amherst public; 2) enters into a written agreement to “eliminate, minimize, or mitigate” the “adverse effects” that the MHC has now determined the project to have on the Jones Library; and 3) redesigns the project accordingly.

Good luck!

Sarah McKee was an Amherst resident for more than 20 years. She is a former president of the Jones Library Trustees and is a member of the D.C. Bar.

Sarah,

Thank you for this step by step, comprehensive explanation of the law and how and where proponents of the Jones Library Plan have thumbed their noses at it.

This does make me wonder how the yay- sayers (regarding the plan) truly feel about democracy and its principles of governing requiring adherence to the rule of law.

How egregious must the misrepresentations be before a grant application might fall under this rubric?

https://www.grants.gov/learn-grants/grant-fraud/grant-fraud-responsibilities.html

Good article, Rob, but it applies to grants from the federal government only. As to those, generally a misrepresentation must be of a material fact, which may be concealed or covered up; must be false, fictitious, or fraudulent; and must be made knowingly and willfully.

These were in a grant application submitted to the Massachusetts Board of Library Commissioners (MBLC). Their legal implications were scarcely trivial. Yet I have never seen or heard anything to indicate how they came to be made.

What I find truly remarkable is this: that so many Amherst officials signed this grant application, despite its readily-spotted misrepresentations (Grant Application: mandatory fields, top of page 8). Yet, when concerned Amherst residents brought the Jones Library’s accurate historic status to the attention of both Town officials who had signed and the MBLC, neither the Town nor this agency of the Commonwealth did anything about it.

How naive were we 5± years ago?! It was interesting to look back and see how the very first news article in The Indy

https://www.amherstindy.org/2019/03/31/jones-library-building-project-must-change-to-qualify-for-state-grant/

that calmly urged for the necessary changes, which when ignored by those in charge helped set the stage for where we still remain….

According to the FY25 budget, Amherst pays more than $120,000 a year for legal services. Why haven’t its well-paid attorneys, KPLaw, been able to provide the Town with the information Sarah McKee has laid out pro bono, and has been calling to the attention of Town leaders since 2016?

Instead KPLaw has coached the Clerk’s office on invalidating citizen’s signatures in a petition to veto library project funding and advised the Amherst Historical Commission liaison to ignore the state commission’s attempts to protect the Jones Library’s historic character.

You raise a valid point, Jeff!

On behalf of the Jones Library supporters of Save Our Library, since 2016 I’ve been citing Title 950, Code of Massachusetts Regulations , Section 71.00, “Protection of properties included in the State Register of Historic Places,” as the law that the Town Manager and Jones Library Trustees must follow for their demolition/expansion/”Rehabilitation” project.

In all those years, no one has ever said or written that some different State historic preservation law in fact accompanies State grants for projects on State Register of Historic Places properties. The 1928 Jones Library, of course, is on both the State and National Registers.

If Town and Trustees had done what those regulations require, and had accordingly consulted with the Massachusetts Historical Commission “as early as possible in the planning process” to ensure that their demolition/expansion “Rehabilitation” project would “protect the Jones Library’s historic character,” either 1) this project would have been completed long ago, or 2) we would have learned that the Massachusetts Board of Library Commissioners (MBLC) insists, as a condition of its $15 million construction grant, on demolishing the historic Library’s original interior walls to create large, open spaces with sightlines.

Actually, my view, the MBLC ought to have made that “sightline” condition clear from the beginning. Springing it on the Town and Trustees only 8 years later is scarcely fair.

Full disclosure early on about this unspoken MBLC requirement would have saved a small fortune in public money, both Town funding and the $2.7 M in State grant funding that the MBLC disbursed to the Town in 2021. It would also have saved untold hours of many people’s time. Whew!