The Mill River in Amherst: The History You Probably Don’t Know

The Red mill, on the mill river in Cushman from the Early Industrial period (1830-1870). Photo: amherstma.gov

A version of this article appeared previously in The Amherst Current. It is reposted here with permission.

Bryan Harvey Lecture: The Mills of Factory Hollow, March 14

Bryan Harvey will be the speaker at the Amherst Historical Society’s “History Bites” lecture series on March 14 from 12:30-1:30 p.m. at the Bangs Center, 70 Boltwood Walk. Harvey will speak about the Mills of Factory Hollow in North Amherst and the ongoing District One Neighborhood Association’s Mill River History Project. A summary of what the Project has learned to date is provided below.

The Mill River in North Amherst: The History You Probably Don’t Know

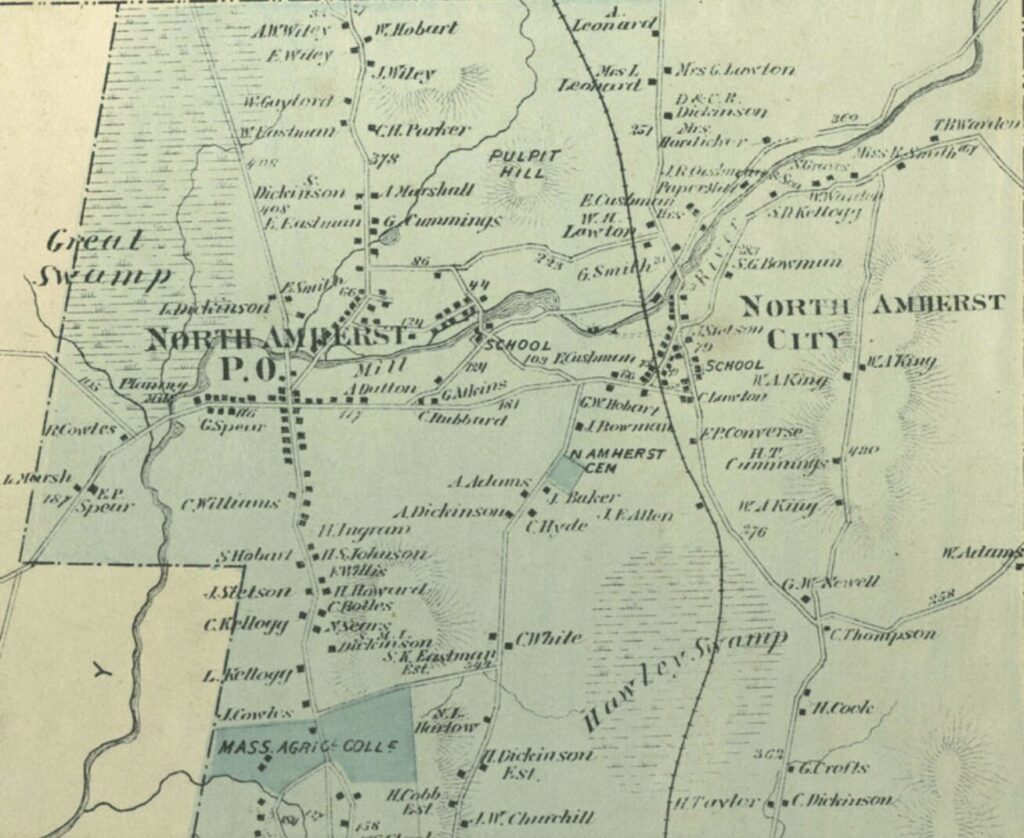

Driving along Pine Street in North Amherst, you may have noted that the road falls off on one side to a deep ravine. Visiting Puffers Pondyou may have wondered why there is a pond there at all. Venturing down the Mill River Conservation Trail you may have noticed a few piles of rubble, or paused briefly at some long-crumbled stone foundation. But you may not appreciate that the name “Mill River” is about all that is left of what was once the most heavily industrialized section of Amherst, home to dozens of mills and factories over a period of more than two centuries. The rise — and fall — of that dynamo is one of the most remarkable stories in Amherst’s history, yet it is one we have only dimly understood.

Three years ago, the District One Neighborhood Association (DONA), a community group focused on life in much of North Amherst, took on the task of exploring the Mill River through time. With a small grant from the town’s Community Preservation Act, we commissioned a fascinating historical and archaeological examination of a few known sites — including two early paper mills upstream of Puffer’s Pond. A second CPA grant this year allowed us to engage a historical consultant and begin to rediscover the full extent of activity along the River from where it tumbles down into Amherst from Leverett and Shutesbury in the north to where it meanders into Hadley near the intersection of Meadow Street and the Route 116 bypass.

And the extent is certainly full. Beginning in 1727 the River powered a whole series of grist and saw mills to serve the then sparse and agrarian community which began as part of Hadley’s “Third Precinct.” The turn of the nineteenth century saw the beginnings of a shift to manufactured goods for trade. Daniel Rowe built a paper mill in 1798 (remains of which can still be seen), using a laborious hand-production process to make fine rag paper which he shipped to Albany via oxcart. Also in 1798 Ebenezer Ingram built a woolen fulling mill up at “the great falls” (by the current bridge on Bridge Street).

And then in 1809 “modern” industry came to the river: Ebenezer Dickinson (a distant relative of Emily’s) erected the Amherst Cotton Factory, a large and modern-for-its-time textile mill just downstream of the Factory Hollow Pond (now Puffers), on the site of the current Mill Hollow Apartments.

The race was on. In just the brief period 1830-38, the Cushman family built its first modern paper mill up on East Leverett Road; the Ingram family built a second fulling mill downstream of the first; Alvin Barnard constructed a forge (later reputed to manufacture equipment for the new railroad); and the Dickinsons built a grist mill on Montague Road that stands to this day (acquired by the Puffer family in 1844, who operated it continuously for the next ninety years).

An industrial frenzy followed. By the onset of the Civil War the river had added another three paper mills and six textile mills of various kinds. The Hills Palm Hat Company, a well-known industry in downtown Amherst, opened a plant on the Mill River in 1856.

The post-War decade was quiet, as the national economy shifted, water power started to give way to steam (and eventually electricity), and the relatively modestly sized Amherst mills struggled to compete with large-scale operations in Holyoke, Chicopee, and other sites on the Connecticut River. By this time many of the Amherst factories had burned or been washed away.

But a final industrial chapter in the river’s story spanned the turn of the twentieth century. The textile mills were either gone or going, but paper still used the river for the manufacturing process if not for power. The Cushman paper mills off Bridge Street were replaced with large factories producing leatherboard, paper towels, carbon paper, and other specialty products. Substantial planing mills were erected downstream, producing sashes, doors, and other wood products. And in 1910, the Puffer family built its Ice House on the current beach at Puffers Pond and harvested and distributed ice from the Pond until well into the 1930s.

But by 1940 nearly all the traces were gone. The large mill pond above the bridge at Bridge Street was drained; the mostly wood structures of the mills had disappeared; and the river’s course was mostly deserted. In the 1960s, the town began to acquire much of “Factory Hollow” for conservation purposes.

But while the factories are gone, the North Amherst and Cushman communities that grew up around them remain, and the stories of the lives of those who lived and worked there still echo down the years. Those of us working on the project have found it endlessly fascinating.